Crew

Director – Steven Spielberg, Screenplay – Joe Cornish, Steven Moffat & Edgar Wright, Based on the Comic-Books The Crab with the Golden Claws, Red Rackham’s Treasure and The Secret of the Unicorn by Hergé, Producers – Peter Jackson, Kathleen Kennedy & Steven Spielberg, Music – John Williams, Senior Visual Effects Supervisor – Joe Letteri, Visual Effects Supervisor – Scott G. Anderson, Animation Supervisors – Jamie Beard & Paul Story, Animation/Visual Effects/Conceptual Design – Weta Digital, Motion Capture – Giant Studios. Production Company – Paramount/Columbia/Nickelodeon Entertainment/Hemisphere Media Capital/Wingnut Films/Kennedy-Marshall.

Cast

Jamie Bell (Tintin), Andy Serkis (Captain Archibald Haddock/Sir Francis Haddock), Daniel Craig (Ivan Sakharine/Red Rackham), Simon Pegg (Thompson), Nick Frost (Thomson), Toby Jones (Aristides Silk), Mackenzie Crook (Tom), Daniel Mays (Allan), Kim Stengel (Bianca Castafiore), Gad Elmaleh (Omar Ben Salaad), Enn Reitel (Nestor/Mr Crabtree), Sonje Fortag (Mrs Finch)

Plot

The reporter Tintin finds the model of a 17th Century sailing ship The Unicorn in the marketplace and buys it. Immediately after, he has people trying to buy and then steal the model off him. Curious, he seeks out the story behind The Unicorn and finds that it was the pirate ship of Sir Francis Haddock. He realises that Sir Francis bequeathed a model ship to each of his three sons and that each model contains a parchment that leads the way to his treasure when combined. Tintin is abducted and crated up aboard the freighter Karaboudjan by the ruthless Sakharine who is determined to obtain the three pieces of the parchment. Tintin manages to get the aid of the ship’s drunken captain, before discovering that this is the current descendant of the Haddock line. Tintin and Captain Haddock escape in a dinghy and race to get to Morocco before Sakharine lays his hands on the last piece of the parchment.

The Tintin comic-books were a treasured part of my childhood. Tintin was the creation of the Belgian writer-illustrator Georges Remi (1907-83), better known as Hergé (after the French pronunciation of his initials reversed). Hergé originally created Tintin as serialised stories in a weekly strip in the Catholic newspaper Le Vingtieme Siecle beginning with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929-30). After World War II, these were republished in colour and new titles added in a series of books that eventually spanned 23 volumes. It was here that Tintin gained his greatest popularity, the books selling millions of copies the world over in numerous translations. Although many are mundane adventure stories, a number of the Tintin stories do venture into fantastic material – the building and launching a Moon rocket in Destination Moon (1953) and Explorers on the Moon (1954); the quest for a fallen meteorite with strange powers in The Shooting Star (1942); an Inca curse in The Seven Crystal Balls (1948) and Prisoners of the Sun (1949); the Yeti as a background character in Tintin in Tibet (1960); and the Erich von Daniken-influenced story of alien visitors in Flight 714 (1968).

Hergé grew up an enthusiastic Boy Scout and published his first cartoon work in a scouting magazine – Tintin, the eternal boy-man, is the ultimate Boy Scout. Hergé’s mentor, the right-wing Catholic bishop Norbert Wallez, had pushed him to create Tintin as a Catholic hero and the first two Tintin stories published under Wallez’s editorship, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Tintin in the Congo (1931) hold respectively viewpoints that are anti-Communist and justify Belgium’s appalling colonial record in the Congo. Thereafter, Hergé took more control of his work and from The Blue Lotus (1936) on determined to place greater emphasis on researching the cultures that he depicted, having photographs of the globe-trotting areas the story took place sent to him so that he could accurately draw these as backgrounds. The Wartime era caused much in the way of problems for Hergé – he accepted what is debated as a collaborationist position with the Nazis where he published five-and-a-half Tintin works in the German-controlled newspaper Le Soir. The post-War period saw him banned from work in newspapers for several years as an accused collaborator, before he began the publication of the Tintin strips in the book form. In subsequent years, Hergé underwent many personal and health crises, including several nervous breakdowns, even at the same time as he saw Tintin become a worldwide success that made him wealthy.

The Tintin stories have appeared on film a number of times. There was a Belgian-made stop-motion animated version of The Crab with the Golden Claws (1947) but this has only had two screenings before the producer was declared bankrupt and fled the country. There were two French-made live-action films Tintin and the Mystery of the Golden Fleece (1961) and Tintin and the Blue Oranges (1965) starring Jean-Pierre Talbot as Tintin; a one-hour Dutch-made animated adaptation of The Calculus Affair (1964); two feature-length animated films, Tintin and the Temple of the Sun (1969), adapted from Prisoners of the Sun, and the original story Tintin and the Lake of Sharks (1972). The best adaptation was the Canadian-made animated series The Adventures of Tintin (1992), which adapted each episode directly from the original comic-strips extremely closely, even down to retaining the comic-strip panels as directorial set-ups. Also of interest is Tintin and I (2003), a documentary about the life of Hergé and attendant controversies.

The Adventures of Tintin is a big-budget film from no less than Steven Spielberg, the most successful film director in the world. (See below for Steven Spielberg’s other genre films). Spielberg first learned of the Tintin comics when he was making Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and either (accounts vary) someone showed him the comics or he read about them in a French-language review, where obvious similarity was drawn between Tintin and Indiana Jones and their globe-spanning 1930s period adventures in exotic locales. Spielberg obtained the rights to Tintin in 1984, initially intended to make a live-action film version.

However, after going to see Peter Jackson in the 00s about the possibility of using the Weta Workshop to produce a CGI version of Snowy, Jackson persuaded Spielberg to make the entire film in the motion capture animated process that had been highlighted very successfully first with the digital Gollum in Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002) and a couple of years later in Robert Zemeckis’s The Polar Express (2004), which pioneered motion capture in terms of full-length animation. Spielberg went down to shoot on Jackson’s digital stages in Wellington, using the Weta Workshop to not only motion capture but animate the film, as well as casting Jackson’s Gollum Andy Serkis as his Captain Haddock. In what is rapidly turning into a boy’s club, Jackson and his Wingnut Films also co-produce The Adventures of Tintin with Jackson taking a producing and second-unit directing role – Spielberg returned the favour by acting as executive producer on Peter Jackson’s afterlife flop The Lovely Bones (2009). Two further Tintin films are planned in what will eventually be a trilogy, with Peter Jackson said to be directing the next of these.

There is an onus on Steven Spielberg when he conducts an adaptation like this from me and the millions of fans who laughed and thrilled to the Tintin stories to do it right. I had a certain problem after viewing the film’s trailer in seeing that Spielberg had opted to make The Adventures of Tintin with a very dark tone (even more so behind the 3D glasses) and densely facially textured characters, which is at almost opposite remove from the distinctive ligne claire style that Hergé patented in the comic-books where the emphasis was on clearly outlined characters and richly colourful and detailed backgrounds. (I have always insisted the greatest cinematic inheritor of the ligne claire style was Japan’s Hayao Miyazaki of Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away (2001) fame).

That said, The Adventures of Tintin makes a scrupulous effort to get the details of the Tintin stories right. Steven Spielberg and his team get down all the familiar idiosyncrasies of the characters – Tintin outfitted in his blue jersey, knickerbockers and ochre trench coat; Captain Haddock in his seaman’s outfit with anchor emblazoned on the chest and array of colourfully apoplectic insults; the moustachioed and bowler-hatted detectives Thompson and Thomson and their endless malapropisms and “to be precises”; Snowy, Bianca Castafiore, Nestor, Marlinspike Hall. The opening credits sequence and the newspaper articles framed on the walls of Tintin’s apartment make reference to other Hergé adventures. The film even opens with Tintin in the marketplace having his portrait done in the style of the comic-books and the artist turning out to be an animated likeness of Hergé. In these scenes, the film is a Tintin fanboy’s dream come true.

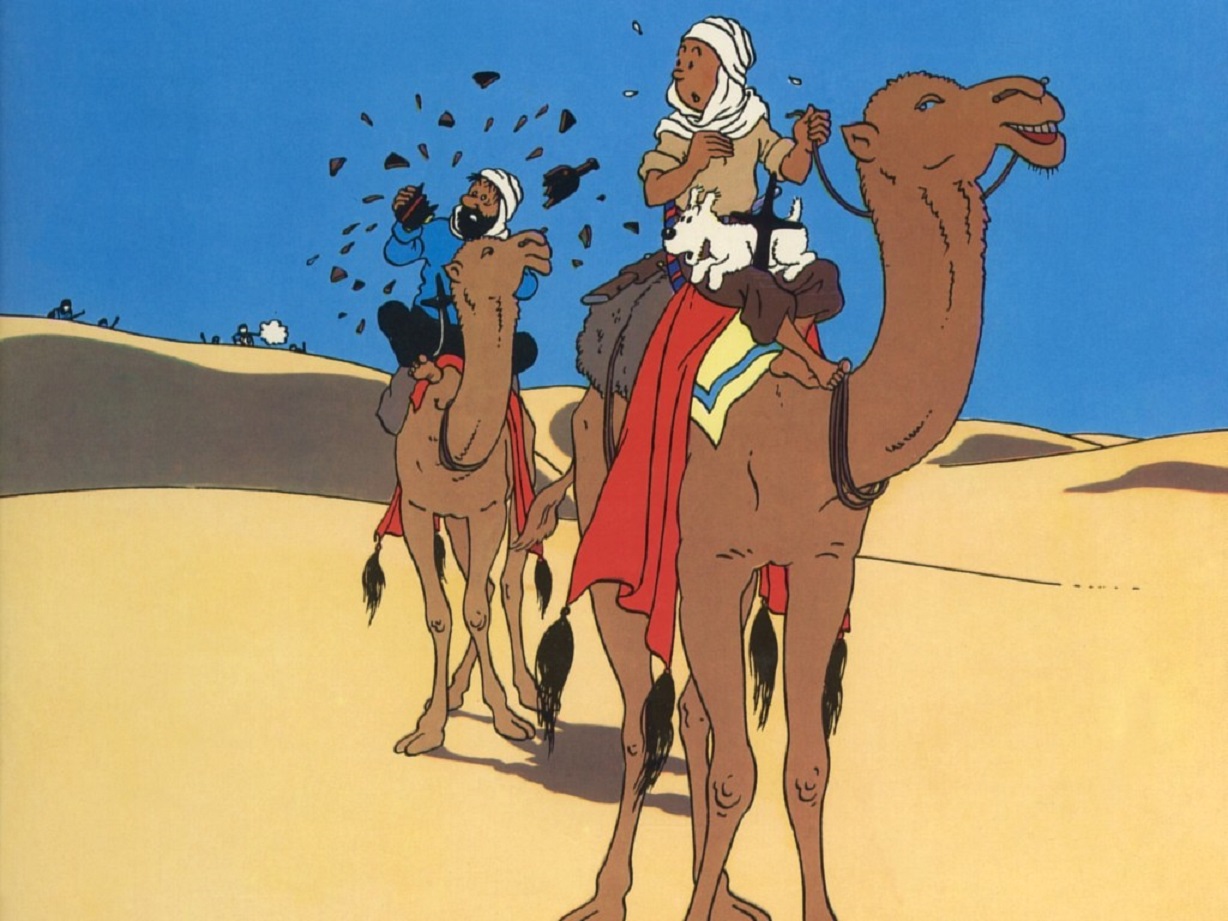

The screenplay comes from an impressive trio of talents – Steven Moffat, the current torch holder as producer and principal writer of the huge hit of the revived Doctor Who (2005– ) and other fine works such as the modernised tv versions of Jekyll (2007), Sherlock (2010 – ) and Dracula (2020); Edgar Wright, the director of Shaun of the Dead (2004), Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010) and The World’s End (2013); and Joe Cornish, director of the British sleeper hit Attack the Block (2011). Cornish, Moffat and Wright play mix and match with three Tintin stories – The Secret of the Unicorn (1943) and Red Rackham’s Treasure (1944), a two-parter concerning the hunt for the treasure, and The Crab with the Golden Claws (1941), a story about drug-smuggling set in Morocco that is most famous for having introduced Captain Haddock, from which has been borrowed the escapades at sea aboard the Karaboudjan, Tintin and Captain Haddock’s escape by dinghy and sea plane and their becoming lost in the desert.

The script does rearrange scenes from the books, as well as invents a number of other wholly new sequences. For example, the film ends with Tintin and Captain Haddock following the map coordinates to find the treasure hidden inside Marlinspike Hall, which follows the eventual ending of Red Rackham’s Treasure. However, this seems to shortcut the bulk of everything else that happens in Red Rackham’s Treasure, omitting the venture to the West Indies and deep-sea diving adventures before the party comes away empty-handed and then returns to find the real hiding place of the treasure in Marlinspike Hall. Indeed, the ending here seems to reverse the two stories where, after finding the treasure, Tintin finds the real map and the film ends with the suggestion that this will take them off on their expedition to sea. Not to mention that Red Rackham’s Treasure is the story where we were introduced to the wonderfully eccentric character of Professor Calculus whose absence is sorely missed in the film.

Some of the supporting characters have to be altered to fit the new story – Sakharine goes from a minor character in The Secret of the Unicorn who was no more than a collector of model ships seeking to add The Unicorn to his collection to become a major villain and a descendant of Red Rackham; in The Crab with the Golden Claws, Omar Ben Salaad was a wealthy merchant who was revealed to be the leader of a drug-smuggling operation but in the film is turned into the sheik of Bagghar and with no apparent criminal involvement. That said, The Adventures of Tintin certainly holds up all the essentials in terms of the principal characters, the look and the comic escapades such that you could easily imagine it as having been something written by Hergé himself.

The faithfulness to the comic-strip does however leave the film with certain problems. One of these is that the dictates of modern cinematic audiences are very different to what would be appreciated by audiences in the 1940s when the three stories that the film is based on were written. Hergé took great delight in offering up adventures that took place in exotic locales, which he would research in great detail, whereas nowadays these now seem a little mundane and do not hold as much of a thrill for modern audiences. The attitudes that Hergé wrote with also fall into an undeniable post-19th Century jingoism – back then it was far more acceptable to have comic caricatures of foreigners, which at times even toppled over into undeniable racism, notably the notorious Tintin in the Congo (although Hergé later repudiated this). To its credit, The Adventures of Tintin keeps scrupulously to the 1930s/40s period setting – where the designers do a fabulous job of giving three-dimensional life to this world – and the film thankfully does not go the disastrous route of attempting to modernise Tintin.

On the other hand, Steven Spielberg is required to have to amplify the dramatics of the original adventures somewhat more than on the comic-book page in order to give us a film that works for modern audiences. Familiar scenes are replicated from the comic-book – Tintin and Captain Haddock escaping from the Karaboudjan, the plane’s strafing run on the dinghy, the passing through the storm and crashing in the desert, the flashbacks to the story of Sir Francis Haddock and Red Rackham – but these have been pumped up into far more elaborate sequences than Hergé ever envisioned them because the film is required to work as a modern action-adventure. This does of course bring Steven Spielberg back into the territory of the Indiana Jones films. In comparison, The Adventures of Tintin seems altogether the more quieter film where the action scenes lack the same relentless energy. The one sequence that does stand out with a good old Spielbergian kinesis is the one with Tintin and Captain Haddock pursuing Sakharine’s thugs through the Bagghar marketplace on a motorcycle and sidecar that comes apart during the chase at the same time as the streets are being flooded after Captain Haddock accidentally fires a bazooka at the dam. Certainly, there is much more of an emphasis on comedy here than in the Indiana Jones films. Comedy is something that has never worked terribly successfully in Steven Spielberg’s hands – look at his failed attempt to make a screwball comedy with 1941 (1979) and the crude farce to which the Indiana Jones sequels frequently descended. That said, Spielberg does reasonably successfully here – largely by keeping as close to the spirit of Hergé as possible with gags set around Captain Haddock’s drinking and bumbling, or the constant prattishness of Thompson and Thomson.

The Adventures of Tintin works reasonably well, even if I don’t think it ever hits greatness. As such, I rank it somewhere down there among second rung Steven Spielberg films – above flops like Hook (1991) and The Terminal (2004), more in the territory of enjoyable popcorn fare that never quite strikes masterpiece territory such as Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and War of the Worlds (2005).

Steven Spielberg’s other genre films are:- Duel (1971), LA 2017 (1971), Something Evil (tv movie, 1972), Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Always (1989), Hook (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001), Minority Report (2002), War of the Worlds (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), The BFG (2016) and Ready Player One (2018). Spielberg has also acted as executive producer on numerous films. Spielberg (2017) is a documentary about Spielberg.