USA. 2012.

Crew

Director – Benh Zeitlin, Screenplay – Lucy Alibar & Benh Zeitlin, Based on the Play Juicy and Delicious by Lucy Alibar, Producers – Michael Gottwald, Dan Janvey & Josh Penn, Photography – Ben Richardson, Music – Dan Romer & Benh Zeitlin, Visual Effects – Academy of Art University (Supervisor – Catherine Tate) & Space Division, Special Effects Supervisor – Neil Stockstill, Auroch Effects – Ray Tintori, Production Design – Alex DiGerlando. Production Company – Court 13/Cinereach/Journeyman Pictures.

Cast

Quvenzhane Wallis (Hushpuppy), Dwight Henry (Wink), Levy Easterly (Jean Battiste), Lowell Landes (Walrus), Pamela Harper (Little Jo), Gina Montana (Miss Bathsheeba)

Plot

Young Hushpuppy lives with her father Wink on the island known to the locals as The Bathtub, which is in Louisiana but separated from the mainland by the levees. Hushpuppy has a view of the world in which she believes that all things need to fit together to work properly. He father returns from a stay in hospital. Upset at being abandoned on her own, Hushpuppy shoves him and is frightened when he collapses. Believing she has broken him, she fears the world is coming to an end. This seems born out when the island is hit by a severe storm. In the aftermath, the island is flooded and the locals are left having to survive with their homes underwater. Hushpuppy and her father are forced to leave by a mandatory evacuation order but resent doing so. Hushpuppy also believes that prehistoric aurochs have been unleashed from the melting ice caps and are rampaging across the landscape.

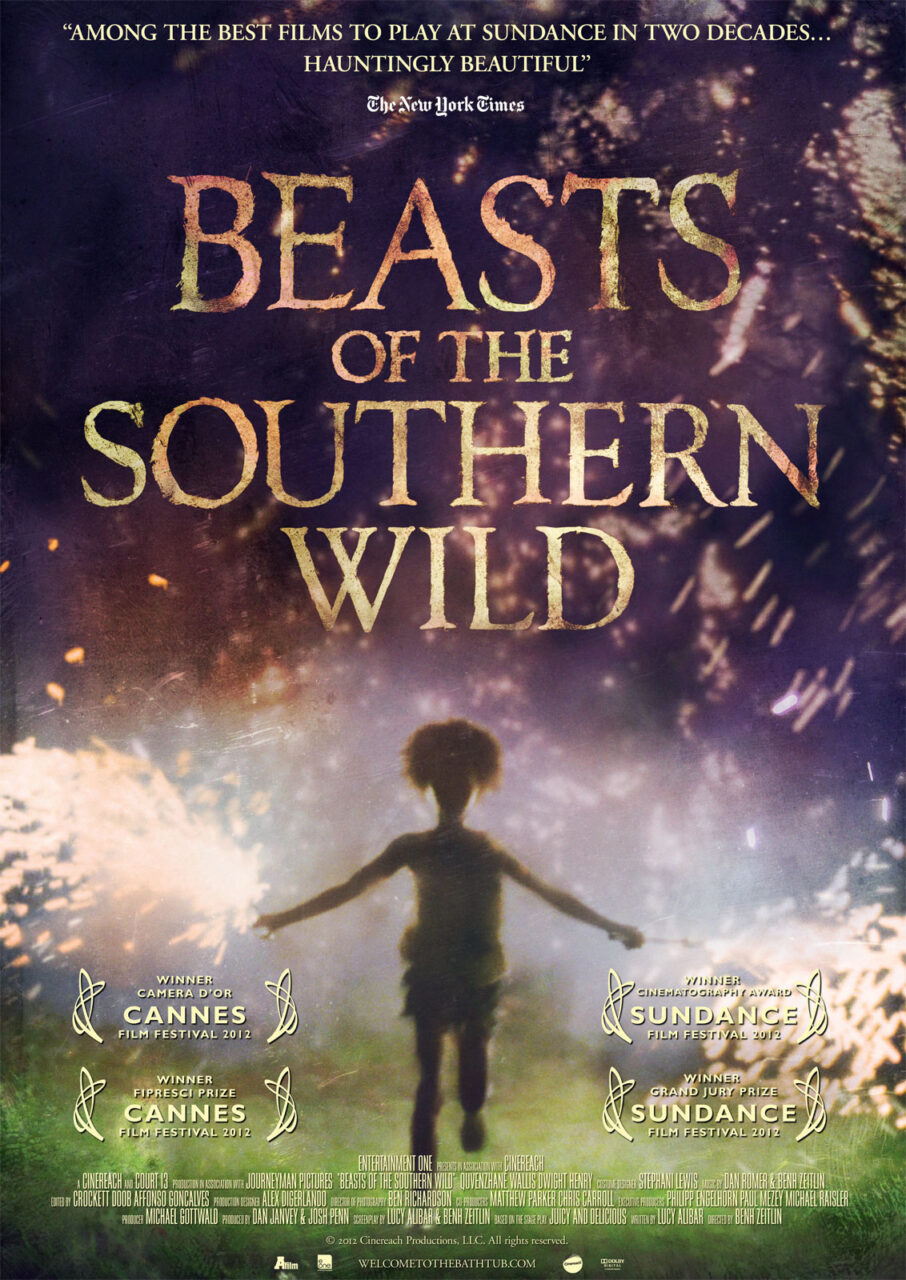

Beasts of the Southern Wild became a world-acclaimed breakout success following its premiere at the 2012 Sundance Festival where it won the Grand Jury Prize, as well as four prizes at the year’s Cannes Festival, including the Golden Camera for best directorial debut.

Director Benh Zeitlin based the film on Juicy and Delicious (2000), a one-act play by Lucy Alibar (who co-writes the film with Zeitlin). There are considerable differences between the play and film – Alibar always sets her work in her native Georgia and it was Zeitlin who came up with the idea of translating it to Louisiana. (In the play, the character of Hushpuppy is also a boy rather than a girl). The film had originally been selected for workshopping at Sundance. Benh Zeitlin recruited most of the cast from non-professionals who had never acted before.

On one level, Beasts of the Southern Wild sets out to be an ethnographic documentation of the lifestyle of the people of the real-life Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana, a small islet that is slowly disappearing into Terrebonne Bay. You have no idea whether the film’s depiction of the island’s ramshackle culture that seems to exist apart from the rest of the world is one that really exists or has been fictionalised for the film – it seems difficult to believe that people in the US would live in such impoverished conditions.

In any other film, you would be expected to express a certain horror at the squalor of the ramshackle homes and alcohol problems the people of The Bathtub have, while some of Dwight Henry’s parenting methods would leave child social services doing a double-take or three. Contrarily, Benh Zeiltin observes without any kind of judgement – at most, the triumphal march that ends the film is one that demonstrates an admiration of the community spirit of these outsiders.

Perhaps one of the most unique aspects of the film is the production design where it seems that every aspect of the world around the characters is something that has been salvaged from scrap, leading to a uniquely colourful hand-built look that is a small work of art in itself.

Although it is never directly specified as such, the events of Hurricane Katrina that devastated Louisiana in 2005 hang over Beasts of the Southern Wild. Certainly, Benh Zeitlin portrays the devastation in ways that are very different to any other film likely to be made about the event, which would likely go either for the disaster movie approach or human melodramatics. The film is directed in terms of a series of surreal drifts through images of the culture and of the survivors trying to cope in the aftermath of the disaster. The scenes where the locals are placed in the quarantine hospital shows the world beyond The Bathtub as a culture that is almost alien to them.

The film’s most unique aspect is its voice. Six year-old Quvenzhane Wallis gained a great deal of attention for her performance – even ended up receiving an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress. The performance itself is unremarkable – what people seem to be drawn towards is the contrast of the realistically grounded world she lives in and the way she narrates, giving a sometimes witty, sometimes potently imagery-laden outlook of everything via a child’s logic that conflates simple events into the mythological. The storm is seen in terms of a primal view of the world, a beacon on the horizon becomes a light beckoning from her lost mother. Even Quvenzhane’s visit to a floating brothel in the midst of the bay is built up into a magical journey into an Aladdin’s cave of light bulbs.

The film is also a Magical Realist one. One of the predominant images throughout is that of the aurochs – giant prehistoric animals that appear to be brought to life out of an iceberg that has been thawed by global warming. You are never entirely sure if the aurochs are meant to be metaphorical or actual – you presume the former until near the end where Benh Zeitlin stages a confrontation between the aurochs and Quvenzhane Wallis.

The one complaint about the film might be that it uses this as symbolism that never seems to particularly connect to anything – you are never sure what dark force the aurochs represent and what their bowing down to Quvenzhane Wallis at the end is meant to mean.

Benh Zeitlin has been readily compared to the obvious influence of Terrence Malick of Badlands (1973), Days of Heaven (1978), The Thin Red Line (1998), The New World (2005) and The Tree of Life (2011) fame. Like Malick, Zeitlin sees landscape and nature as an echo of inner emotions and much of his film is directed in terms of hauntingly intimate voiceovers. Perhaps more so than Terrence Malick, the filmmaker that Benh Zeitlin’s quasi-mythological view of the world reminded me of the most is New Zealand’s least internationally recognised talent Vincent Ward. Ward crafts similar kinds of films that burst with uniquely alien imagery of the familiar in efforts like The Navigator: A Mediaeval Odyssey (1988) and Map of the Human Heart (1993). In particular, what Beasts of the Southern Wild reminds of is Vincent Ward’s Vigil (1985), which told a similar near-wordless view of life in a remote corner of the world through the eye of a young girl, where the entire film was stripped to a primal landscape told in terms of mythological imagery.

Benh Zeitlin next made Wendy (2020), a modernised version of the Peter Pan story.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2012 list. Winner for Best Director (Benh Zeitlin) at this site’s Best of 2012 Awards).

Trailer here