USA. 2003.

Crew

Directors – Aaron Blaise & Bob Walker, Screenplay – Steve Bencich, Lorne Cameron, Ron J. Friedman & David Hoselton, Story – Broose Johnson & Tab Murphy, Producer – Chuck Williams, Music – Phil Collins & Mark Mancina, Songs – Collins, Visual Effects Supervisor – Garrett Wren, Art Direction – Robh Ruppel. Production Company – Disney.

Voices

Joaquin Phoenix (Kenai), Jeremy Suarez (Koda), Jason Raize (Denahi), Rick Moranis (Rutt), Dave Thomas (Tuke), Joan Copeland (Tanana), D.B. Sweeney (Sitka), Michael Clarke Duncan (Tug)

Plot

Before the beginning of civilization. In an Inuit tribe, young Kenai undergoes the rites of manhood and learns that his totem spirit is the bear. His older brother Sitka is then killed by a bear while hunting. In vengeance, Kenai hunts down and slaughters the bear responsible. As he does so, Sitka, who has gone on to live with the spirits of the dead in the Aurora Borealis, appears and Kenai comes around to find that he is now inside a bear’s body. He realizes that the only way that he can regain human form is to return to the mountain where the Aurora is. He sets out, reluctantly accepting the company of a young bear Koda who has lost his mother. At the same time, his other brother Denahi comes hunting him, believing that he is the bear responsible for killing Kenai and not realizing that the bear is Kenai. During the journey, Kenai comes to understand what brotherhood means and how it is humanity, not the bears, that is the true aggressor.

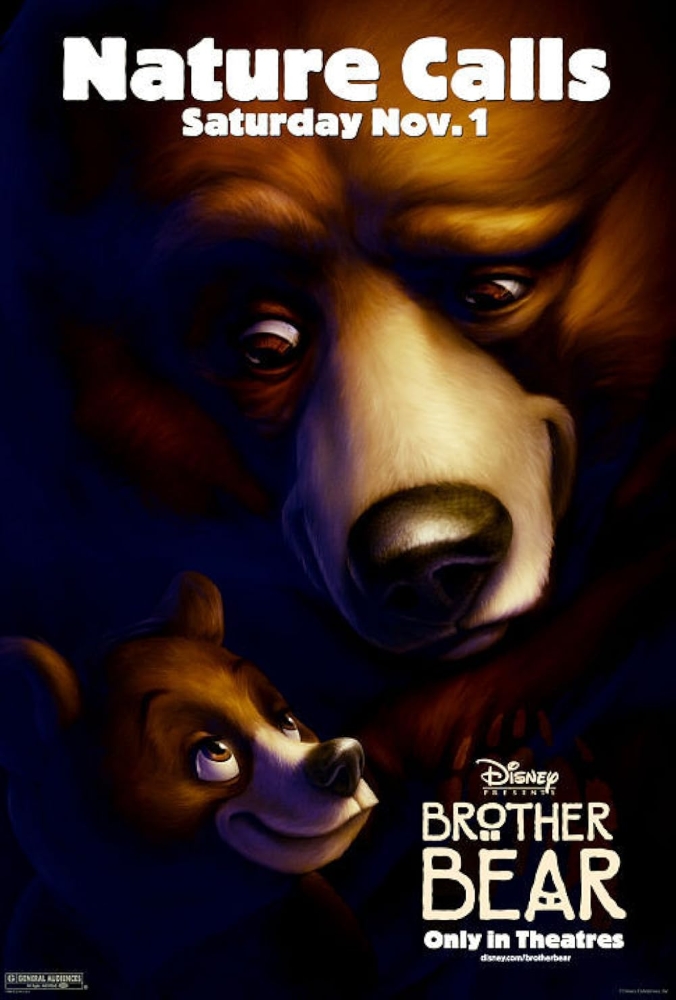

Brother Bear is a Disney animated film. When it came out, Brother Bear received a surprisingly vitriolic response from the mainstream critical American press, with almost all universally dismissing it for a central blandness of heart. It came at a point where the renaissance of high quality Disney animation that had begun with Beauty and the Beast (1991) had started to dissipate in a series of critical and box-office flops. Box-office response for Brother Bear was middling, although this could well have been the thoroughly bland title that Disney chose to slap the film with. However, it did presage a decline that would dog Disney animation throughout the 00s where their animated films seemed to lose their lustre and they turned out a string of head-scratching non-starters.

Brother Bear is not as bad a film as all of this suggested. It is certainly better than some others that have come out of the 1990s Disney renaissance, notably the similar Pocahontas (1995). The film takes up the prehistory setting that has proven popular in animation over recent years with the likes of Disney’s Dinosaur (2000), Ice Age (2002), and before all of these with Don Bluth’s The Land Before Time (1988).

A number of films of the 1990s Disney renaissance have in a desire to appeal to wider audiences taken up various other cultural backdrops – Native American culture and spirituality in Pocahontas, Chinese culture in Mulan (1998), an Hawaiian background in Lilo & Stitch (2002), African-American culture in The Princess and the Frog (2009), even one supposes Aztec culture in The Emperor’s New Groove (2000). Likewise, Brother Bear makes a respectable attempt to use Inuit culture as its backdrop. It suggests a peculiar mix of Ice Age, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001), all shaken up with a few (albeit more seriously minded) dashes of the human-under-animal-transformation-curse plot of Disney’s gonzo The Emperor’s New Groove.

The first quarter of Brother Bear is surprisingly adult in tone. The initial montage of scenes contrasting the youthful playfulness of Kenai and brothers, followed by the shock killing of the brother and Kenai’s swearing of vengeance against the bear all deal in adult emotions that are uncommon for a Disney film. It is rare to have a Disney film where a likeable character is killed and they remain dead (well okay, even then the brother does make several ghostly appearances throughout but he still remains principally dead). As Brother Bear unfolds, it feels as though you are watching a sudden newfound maturity entering the Disney film.

Alas, Brother Bear never sustains this. It takes an abrupt change of pace and with a decided jolt suddenly opens up – quite literally so, going from a three-quarters frame to widescreen (indeed, one thought that what they were initially watching was a film that wasn’t being projected at the correct screen ratio by a novice projectionist) – and turns into a standard Disney talking animals fantasy. The sudden move from strong adult emotions to a barrage of small furry and comic talking animal sidekicks is a jarring change of pace. Even the colour of the film changes during the move, going from a predominantly monochromatic mountain setting to a rich rainbow palette of colours in the forest scenes.

Eventually the talking animals section settles in with a fair degree of likeability. There is quite a strong story arc involving the reversal of Kenai’s beliefs about the bears and the realisation that they are not the monsters but that human perceptions have painted the bears as monsters and that the animals regard human hunters as the aggressors. There is a predictable storyline following the transformed hero and the gradual thawing of his relationship with the cute, adorable sidekick who insists on regarding him as a brother.

Phil Collins delivers several bland songs and maybe some of the montages of the various animals playing and frolicking could have been trimmed but Brother Bear eventually arrives at its conclusion with a modest degree of feeling that never outwears its welcome. The backgrounds of the film are all impressive, without insistently drawing attention to the fact. The comic relief animals are likeable, with SCTV (1976-81) alumni Rick Moranis and Dave Thomas amusingly cast as a duo of dim-witted Canadian-accented moose.

Brother Bear also manages to do all the anachronism-spouting animals – moose aerobics sessions, a stoner bear – without it seeming too jarring, unlike other Disney efforts such as Aladdin (1992) and Hercules (1997). There is a particularly adorable series of skits over the credits, not unlike the ‘outtakes’ in Pixar’s films – although here Brother Bear peculiarly proves to be the second animated film of 2003 to involve gags centred around Georges Seurat’s painting A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884), following Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003).

Disney later released a dvd-sequel Brother Bear 2 (2006).

Trailer here