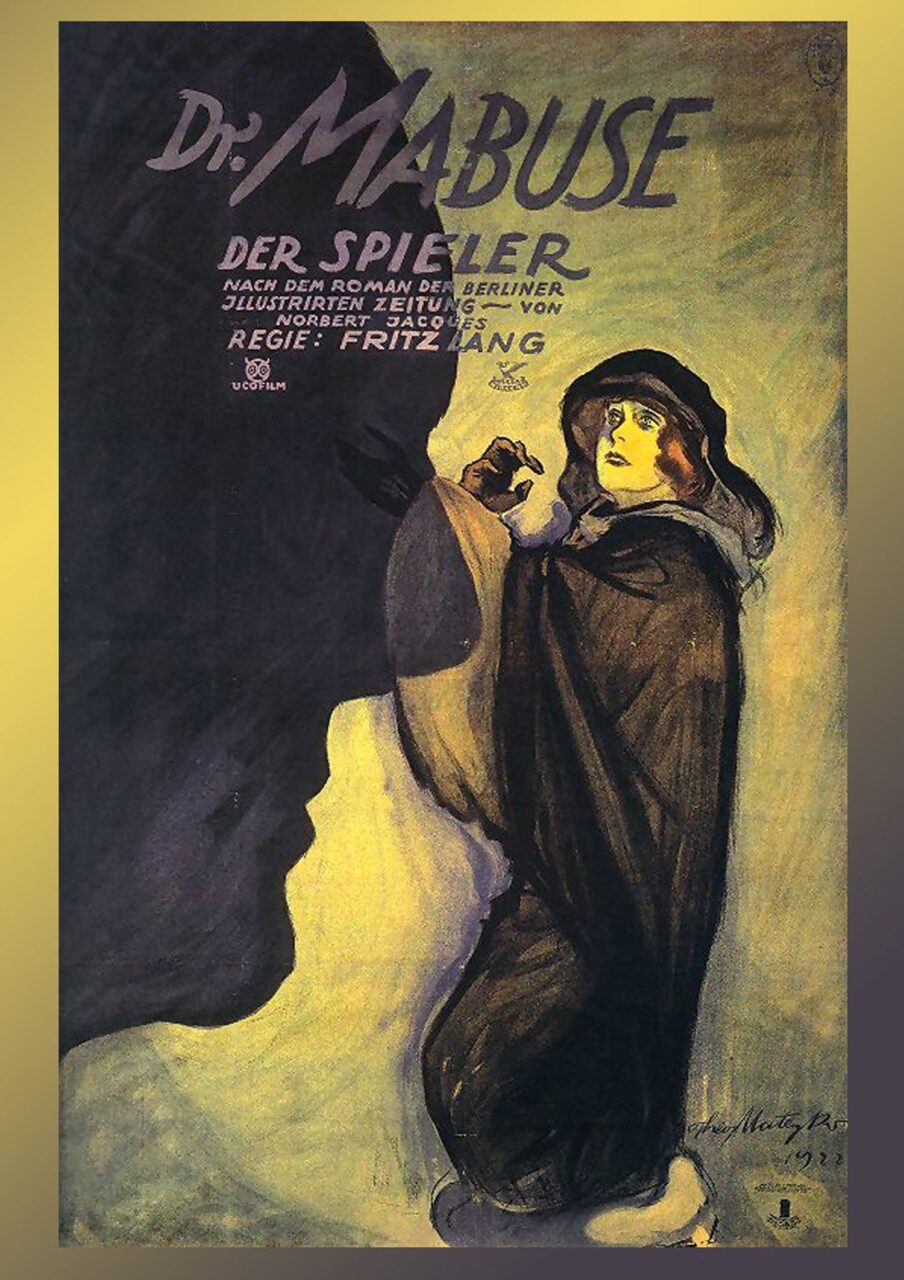

(Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler)

Germany. 1922.

Crew

Director – Fritz Lang, Screenplay – Thea von Harbou, Based on the Novel Dr Mabuse, The Gambler by Norbert Jacques, Producer – Erich Pommer, Photography (b&w) – Carl Hoffmann, Production Design – Otto Hunte & Stahl-Ubache. Production Company – Decla-Bioscop.

Cast

Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Dr Mabuse), Bernhard Goetzke (State Prosecutor von Wenk), Aud Egede-Nissen (Cara Carozza), Gertrude Welker (Countess Dusy Told), Alfred Abel (Count Told), Paul Richter (Edgar Hull), Robert Forster-Larrinaga (Spoerri), Hans Adalbert von Schettow (Georg)

Plot

Behind the guise of a respected psychoanalyst, Dr Mabuse is a criminal genius who is a master of disguise and hypnotism. Mabuse steals state documents that allow him to manipulate the stockmarkets. In the Folies Bergere, he influences the mind of a weak-willed playboy Edgar Hull into losing a fortune at the card tables and then sets him up with Cara Carozza, a dancer he controls. Mabuse’s schemes attract the attention of State Prosecutor von Wenk who becomes determined to find Mabuse’s identity and stop him. As he becomes aware of von Wenk, Mabuse sets a series of traps for him.

Dr Mabuse, The Gambler is one of the great epics of German silent cinema. Dr Mabuse’s influence is enormous – most obviously in its generation of a series of sequels in the 1960s (see below). More so than that, Dr Mabuse is the seed from which the James Bond super-villains were drawn – one can still see Mabuse the calculating criminal genius reflected in contemporary villains like Hannibal Lecter (even if Norbert Jacques and Fritz Lang drew the basic character from Professor Moriarty in Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories).

The character of Dr Mabuse originally appeared in Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (1921), a novel by Luxembourger writer Norbert Jacques. Jacques wrote a couple of other Dr Mabuse novels but these are almost completely forgotten today and what everybody remembers is the various film incarnations. This, the first of the films, was taken on by German director Fritz Lang (1890-1976).

Fritz Lang first emerged as a director with works like The Spiders (1919) and Destiny (1921) and then gained wide acclaim with Dr Mabuse. Lang became regarded as one of the greatest of all directors in the great period of German silent cinema that flourished between the wars where he made epics such as Siegfried (1922), Metropolis (1927), perhaps the most famous of all silent films, Spies (1928), Woman in the Moon (1929) and M (1931). Into the sound era, Lang fled Nazi Germany for France and later America, where he became a regular director of crime thrillers and lived up until his death in 1976. (See below for Fritz Lang’s other genre films).

In Dr Mabuse, Fritz Lang taps into the decadence of post-War Europe – the Folies Bergere, the flourishing gambling clubs, the free-wheeling continental set, the world of international finance, the flourishing of spiritualism. Some of Lang’s images of the bored rich are striking. One of the gambling dens advertises itself: “Hilarious enjoyment without restrictions. Our motto is ‘Whatever Gives Pleasure is Permissible’.” The Countess is wont to stating intertitle cards like: “We need adventure to make life worthwhile” and [of watching people gamble]: “I find thrills and sensations which help to make existence less dull.” In this milieu, Dr Mabuse is seen as the ultimate decadent – “Nothing is interesting in the long run – except one thing. Playing with human beings and human fates,” he states at one point, and at another: “There is no such thing as love. There is only desire – and the will to possess what you desire.”

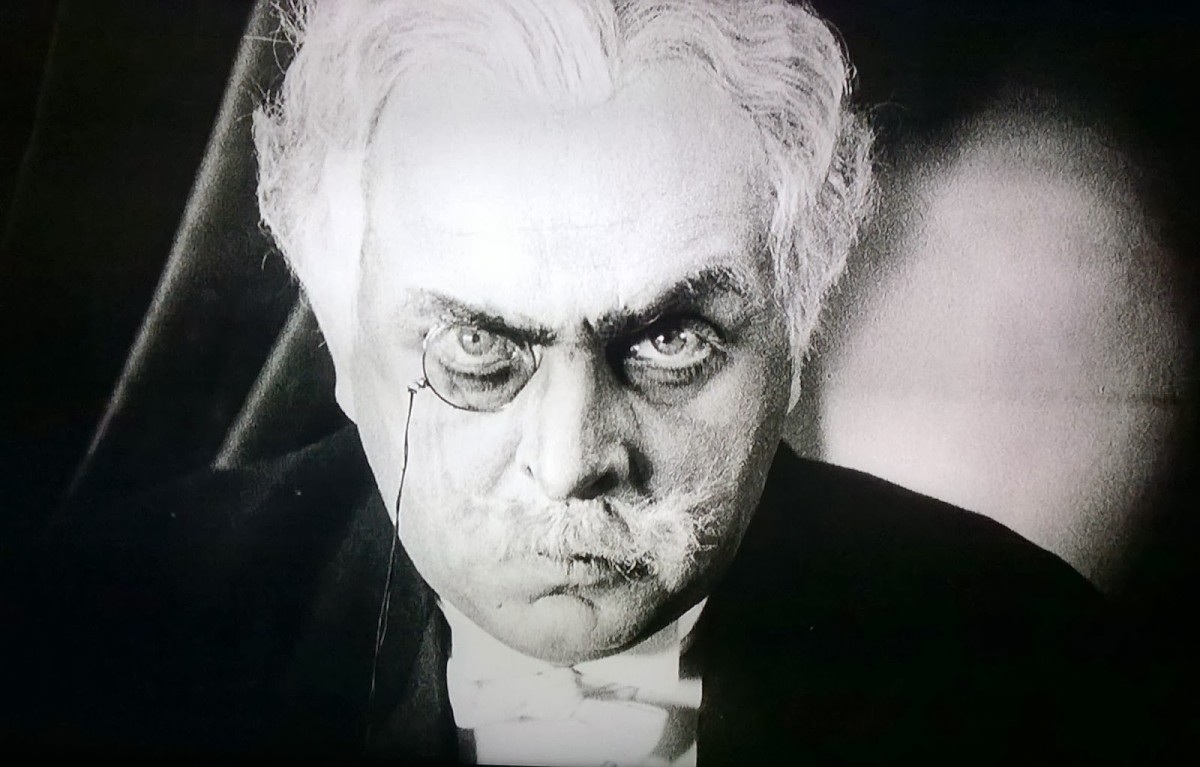

Lang had a fascination with masses being controlled by Machiavellian minds – as in many of his American sound thrillers, or with images like the robot Maria turned rabble-rouser in Metropolis. As Mabuse, Rudolf Klein-Rogge (who was also Rotwang in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the former husband of Lang’s wife/screenwriter Thea von Harbou) physically dominates the film with a ruthlessly brutal performance, glaring right into the screen with a look of pure malevolence. Lang engages in some wonderful cinematic effects to demonstrate Mabuse’s mental powers at work – like a shot that looks up over a player’s cards to show Mabuse’s eyes glowing, which then closes in as everything else goes black until we see nothing except his eyes in the dark. Despite Rudolf Klein-Rogge dominating the film, Lang does a fine job in the creation of his adversary Wenk, which Bernard Goetzke (who was Death in Lang’s Destiny) plays with a steely brilliance.

Lang creates some amazing scenes. There is little in the film that matches the opening act, which starts with a car/train chase and then ventures to the stockmarket (inhabited wholly by men wearing top hats) as they speculate while one figure stands above the crowd calling out “I will buy … I will sell,” before the end of the session and the camera closes in on the figure to reveal it is Mabuse in the first of his disguises. (It is a scene that would have had even more potency back in 1922 where Germany was in the midst of an inflation crisis due to the country’s misguided attempt to deal with War reparations by printing more money, causing a single mark to spiral to millions of times its value over the space of five years). Or the sequence where Rudolf Klein-Rogge sits down opposite Paul Richter at the card table and the Chinese Glasses of his disguise become lit up, hypnotising Richter, where Klein-Rogge becomes lit up by a band of light in the darkness. The screen narrows to place Richter in the centre and the phrase ‘tsi nin fang’ becomes repeated and is even written in glowing letters on the table that Richter cannot seemingly erase as he falls under Mabuse’s control. It is a fabulous sequence that works all by visuals alone, no spoken dialogue. Similar effects are present in the great scene where Mabuse hypnotises von Wenk by posing as a stage hypnotist and gets him to drive to Merliot where the phrase ‘Merliot’ comes shimmering towards us out of the screen as he drives off.

Fritz Lang is a master of mise-en-scene. The texture in some scenes, the detail that goes into creating background characters is extraordinary. The sets are superb – restaurants with massive angular arched roofs, hotel rooms bigger than the lobbies of some hotels. A hotel foyer is dominated by a giant chandelier and beneath it a large circular carpet where the walls of the rest of the room fade into the distance so that there is a single set that almost entirely consists only of the chandelier and carpet with people seen as distant figures circling around it. The most fabulous set is the nightclub where the centrepiece is a large circular table with slides for the patrons to send their bets down, where the croupier emerges from the centre of the table and a giant electrically-lit chandelier descends and opens its wings out to reveal a dancer. This was part of the German Expressionism movement – something that began with The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919), which became a classic because of its highly distorted sets and lighting scheme and had influence of many other films in Germany during this period. Lang and Thea von Harbou readily mock this with Mabuse getting a line “Expressionism’s just playing around. And why not? Everybody’s playing around these days.”

The original German version hails in at nearly five hours in length. The English-language print released in the USA in 1924 is under 90 minutes and was the version available for many years and released to video. Unfortunately, this is not a particularly good translation – as witness the director being called Fritz Lange. The characters, with the exception of Mabuse, have all been renamed – in the German version, for instance, the character of Richard is the Countess’s husband, while in the US version he becomes her brother. A fully restored version was released by the Goethe Institute in 2004, which now runs at 297 minutes. This version gives the complete sense of the story and of the fiendish games that Mabuse plays. On the other hand, there are times you do feel the show is being drawn out and is in need of cutting. The first half-hour of the second half of the story is taken up by a lengthy plot where Mabuse abducts Gertrude Welker with the intention of making her his own, while at the same time her husband Alfred Abel gives himself over to Mabuse who orders that he shut out the rest of the world – something that becomes a long series of scenes that sideline the principal nemeses in favour of these plotting contortions.

The other Dr Mabuse film are:– The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1933), The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), The Return of Dr Mabuse (1961), The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1962), The Invisible Dr Mabuse/The Invisible Horror (1962), Dr Mabuse vs Scotland Yard (1964), The Death Ray of Dr Mabuse/The Secret of Dr Mabuse (1964). The first two of these sequels were directed by Fritz Lang. Dr Mabuse was also modernised by Claude Chabrol as Dr M/Club Extinction (1990).

Fritz Lang’s other films of genre interest are:– Destiny (1921) wherein Death incarnates two lovers throughout various historical periods; the two-part Niebelungen saga, Siegfried (1924) and Kriemhild’s Revenge (1924), based on the Teutonic myths; Metropolis (1927); Woman in the Moon (1929), a realist attempt to portray a Moon landing; M (1931), a thriller concerning the hunt for a child killer; The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1933); the afterlife fantasy Liliom (1933); the film noir psycho-thriller Secret Beyond the Door (1948); and a further Dr Mabuse sequel The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). Lang also wrote the script for Plague of Florence (1919), an adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death (1842)

Full film available online. Part 1 here:-