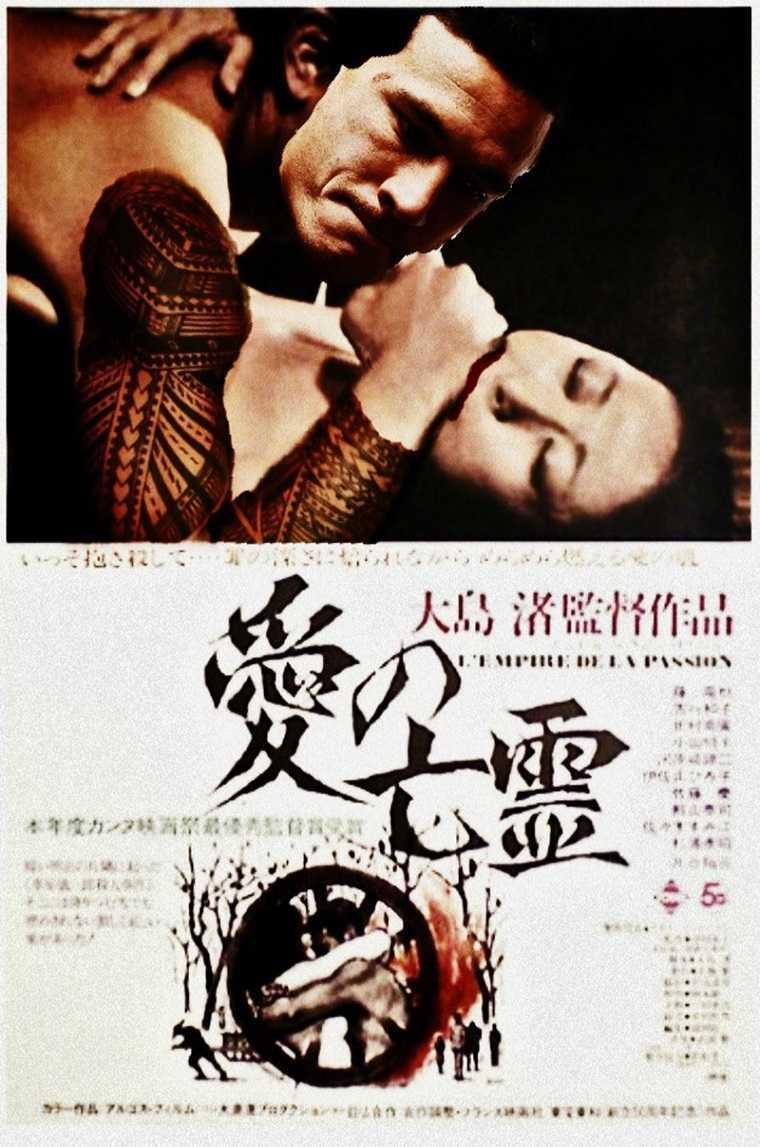

(Ai No Borei)

Japan/France. 1978.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Nagisa Oshima, Based on the Novel Three Generations to Make the Land Fertile: The Earth by Itoko Namura, Photography – Yoshio Miyajima, Music – Toru Takemitsu. Production Company – Argos Films/Oshima Productions

Cast

Kazuko Yoshiyuki (Seki), Tatsuya Fuji (Toyoji), Takahiro Tamura (Gisaburo Desa), Takuzo Kawatani (Inspector Hotta)

Plot

In a small Japanese village in 1895, a wife Seki has an affair with a younger man Toyoji. On the spur of the moment, Toyoji shaves her pubic hair. They then decide that they must kill her husband Gisaburo so that he doesn’t find her shaven. Seki gets Gisaburo drunk and they kill him and dump his body down a well and then pretend that he has gone away to find work. Three years later, Gisaburo returns as a ghost, confused and lost. The guilt of his return drives Seki and Toyoji to desperation.

The kaidan or Japanese ghost story has a long tradition that goes well back to the 17th Century. As a genre, it was popularised in printed fiction around the turn of the 20th Century. The filmed equivalent, the kaidan eiga, emerged in the 1950s and 60s with works such as Ugetsu Monogatari (1953), Ghost Story of Yotsuya (1959), The Ghosts of Kasane Swamp (1959), Jigoku (1960), Kwaidan (1964) and Illusion of Blood (1965), among others.

This venture into the kaidan eiga was highly acclaimed on its release in 1978 but was little seen out of limited arthouse release and has been entirely forgotten since. Director Nagisa Oshima (1932-2013) became a highly respected name in Japanese cinema, having made some forty films during his career, including Night and Fog in Japan (1960), Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969) and In the Realm of the Senses (1976), of which the best known in the West is probably Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (1983). Empire of Passion was his ony venture into genre material.

Far more so than Western ghost stories ever do, most kaidan centre around themes of guilt and retribution. Nagisa Oshima’s twist on the ghost story is that his ghost is not so much an avenging spirit as it is a sad and confused lost soul whose vague stumblings around drive his murderers to guilt and anguish. Oshima’s presages the ghost’s appearances with an eeriness – three years after the body has been dumped down the well, a friend dreaming of Gisaburo telling her to bring him some clean clothes, he is tired of sleeping in the same ones; or his daughter dreaming of him telling her that he will be home by New Year.

Locating the story in a 19th Century rural peasant setting, Oshima employs the style of Japanese post-War neo-realist cinema to considerable effect. At times, the camera does no more than sit impassively observing scenes of extraordinarily raw effect transpiring before it. Throughout the love scenes and the shaving scene Oshima keeps focused on Kazuko Yoshiyuki’s face, watching not the passion or the act but the pain on her face and the effect has cuttingly emotional power. The actual murder plot occurs with astonishing casualness – Tatsuya Fuji shaves Kazuko Yoshiyuki’s pubic hair and then suddenly announces “We must kill him. How can we let him see you shaved?”

Trailer here