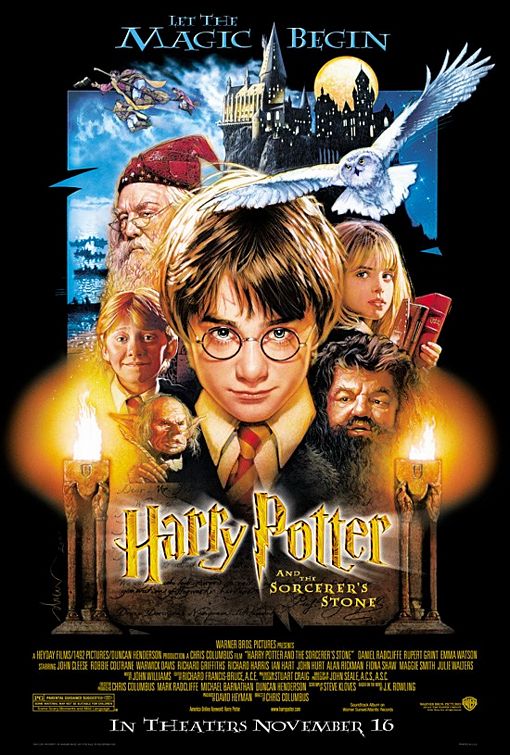

aka Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Crew

Director – Chris Columbus, Screenplay – Steve Kloves, Based on the Novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1997) by J.K. Rowling, Producer – David Heyman, Photography – John Seale, Music – John Williams, Visual Effects Supervisor – Robert Legato, Visual Effects – Cinesite (Europe), The Computer Film Co, Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Roger Guyett), Mill Film Ltd (Supervisor – Karl Mooney), The Moving Picture Co, Rhythm and Hues (Supervisor – Richard E. Hollander), Smoke & Mirrors & Sony Pictures Imageworks (Supervisor – Jim Berney), Special Effects Supervisor – John Richardson, Creature/Makeup Effects Supervisor – Nick Dudman, Creature/Makeup Effects – The Jim Henson Creature Workshop (Supervisor – Jamie Coulter), Production Design – Stuart Craig. Production Company – Heyday Films/1492 Pictures/Duncan Henderson.

Cast

Daniel Radcliffe (Harry Potter), Rupert Grint (Ron Weasley), Emma Watson (Hermione Granger), Robbie Coltrane (Rubeus Hagrid), Richard Harris (Professor Albus Dumbledore), Alan Rickman (Professor Severus Snape), Maggie Smith (Professor Minerva McGonnagle), Ian Hart (Professor Quirrell), Tom Felton (Draco Malfoy), John Hurt (Mr Ollivander), Richard Griffiths (Vernon Dursley), Fiona Shaw (Petunia Dursley), Harry Melling (Dudley Dursley), Zoe Wanamaker (Madame Hooch)

Plot

Harry Potter lives in a cupboard under the stairs with his adopted family, the horrid Dursleys. On his eleventh birthday, Harry receives a visit from the wizard Hagrid who tells Harry that he is the child of two magicians and that he has a promising future ahead of him as a wizard. Harry accompanies Hagrid to Hogwarts School for Witchcraft. There he befriends two classmates Ron Weasley and Hermione Grainger and soon learns all about spells, potions, levitation, broomstick flying and such like. Harry increasingly comes to suspect that the potions master Severus Snape is up to sinister things. Harry, Ron and Hermione discover that a giant three-headed dog on the third floor is guarding the all-powerful sorcerer’s stone, which can transmute metals and grant immortality, and that the stone is wanted by Lord Voldemort, the dark magician who killed Harry’s parents.

The Harry Potter phenomenon is the most amazing thing to hit the publishing world in some time. It has been called “the phenomenon that got kids reading again”. It was the brainchild of J.K. Rowling, a former teacher who wrote the first book in cafes while an unemployed single mother. J.K. Rowling wrote a total of seven books in the series – Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1997), Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1998), Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (1999), Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2000), Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2003), Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2005) and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2007). I must admit to being about the last person in the English-speaking world who has not yet succumbed and read Harry Potter. That said, one has never heard a single word, from adult or child, who does not speak highly of the infectious readability of the stories. This film was the inevitable outthrust from the phenomenon. It became the No 1 box-office success of 2001 and on its opening weekend set box-office records in the US for the highest-ever weekend gross.

One had a dreadful sinking feeling about Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone from the signing on of Chris Columbus. Columbus began as a scriptwriter for Steven Spielberg with films like Gremlins (1984), The Goonies (1985) and Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) and other works like Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989), before making his directorial debut with Adventures in Babysitting (1987) and going onto the nauseating Home Alone (1990) and entirely frivolous light comedies such as Mrs Doubtfire (1993), Nine Months (1995) and Bicentennial Man (1999).

Chris Columbus’s track record only spelt bad things for Harry Potter and it wasn’t helped by the studio renaming the film Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone over the book’s title Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone on the presumable assumption that Americans would not go and see something that sounded too intellectual. Nevertheless, one heard positive moves in that J.K. Rowling had used her clout to insist that the film was faithful to the book (resulting in a film that is 152 minutes long, nearly twice the length of the average feature) and that it be cast with British actors (employing most of the British Screen Actors Guild by the looks of it, with even small cameos filled by the likes of John Cleese, Julie Walters and Geraldine Somerville).

The result that emerges is certainly better than expected. Everyone in the know comments that the film has treated the source material with the utmost respect. Daniel Radcliffe makes a perfect Harry. What one found especially appealing is the film’s capturing of an essential Britishness despite being American made on the other side of the cameras. J.K. Rowling is another writer who fall into a lineage that comes from the Billy Bunter and Ginger stories and the works of Richmal Crompton, all British children’s comedy/adventure stories set around boarding schools. In this respect, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone gets the essence of the boarding school genre with its geriatric school masters, cavernous dining halls, competing sports houses, dorms, British train stations and children’s fascination with sweets down perfect – the film even stages the broomstick-bound equivalent of a soccer game. Much of this will not translate to the American public – indeed, many of J.K. Rowling’s British colloquialisms had to be rewritten for the American editions of the books in order to be understood – and it is nice to see attention paid to it in the film.

No expense has been spared to bring the stories to the screen but that is part of the problem with the film. The magic is portrayed with lavishly spectacular regard – the Grand Hall filled with hundreds of floating candles, a house completely inundated by owl-dropped letters, spectacular broom flights, animal metamorphoses, giant slavering three-headed dogs, centaurs, trolls, shifting staircases and hallways filled with animated portraits. The problem is that the desire to create wondrous effect on the part of Chris Columbus and the nine special effects houses employed by the film ends up becoming so persistent that the result contrarily becomes banally unaffecting.

The film feels over-produced. It is not enough for Chris Columbus to show a street of magician’s shops but it has to be one teeming with wizards as far as the eye can see; it is not merely enough to have one kid accidentally fly off on a broomstick but it has to be a dizzying rollercoaster flight down and around courtyards and buildings; it is not enough to merely have portraits whose figures move but every available foot of wall space in the school has to be covered by them.

One suspects that the way J.K. Rowling told it in the books, the magic was nonchalant and wittily offhand, but here it seems that Chris Columbus and his partner in crime John Williams on the score has to reach for banal awe-filled cues every time one of these set-pieces are introduced. Columbus demonstrated the same problem in Bicentennial Man where he frequently drowned the simple process of telling the story with lavish visions of the future, flashing holograms and banal sentimental nudging every time he wanted to convey a point. For Chris Columbus, battering an audience for wondrousness seems to serve as a substitute for simply telling the story.

A couple of the effects set-pieces do work because Columbus invests them with drama rather than simply putting them there and expecting us to go ‘wow’ – one the game of quidditch, the soccer game on flying broomsticks, a set-piece that one can easily imagine George Lucas having conceived for one of his Star Wars films, and the other the giant-size game of chess. The film tends to work better in the second half than the first, where J.K. Rowling’s control over the film forces Chris Columbus to no longer spend his time introducing set-pieces and instead concentrate on the story. However, for all that Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone promised to be, the results are banal.

In the end, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone is better than one expected it to be, yet not all it could have been. It feels like a film that has been spun out of a multi-media franchise rather than its own entity. The question that should be asked is this – were Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone a film standing on its own and not spun out of a remarkably popular series of books, would it be having the same success? Would it be inspiring child and adult audiences to unqualified levels of delight on its own or does the audience’s delight merely come at seeing what is on the page having been brought to life? The only film that one can compare to the books’ success to is Star Wars (1977) and sequels. Is Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (the film) a Star Wars for the 00’s? Personally, I doubt it.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was followed by Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002), Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004), Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005), Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007), Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009), Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1 (2010) and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2 (2011). Subsequently, J.K. Rowling launched a Harry Potter prequel series with Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016), Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald (2018) and Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore (2022).

Chris Columbus’s other directorial ventures into fantastic cinema include Bicentennial Man (1999), a film about a robot becoming self-aware that reduced Isaac Asimov to agonizingly insipid mush, and the subsequent Percy Jackson & The Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010) about a teen who discovers he is the son of a Greek god and the comedy Pixels (2015) in which alien invaders recreate classic arcade videogames. Columbus has also produced a number of other high-profile fantasy films including Monkeybone (2001), Fantastic Four (2005) and Night at the Museum (2006) and sequels to the latter two, The Witch: A New-England Folktale (2015), I Kill Giants (2017), The Lighthouse (2019), Scoob! (2020), Chupa (2023) and Nosferatu (2024).

(Nominee for Best Musical Score and Best Special Effects at this site’s Best of 2001 Awards. No. 1 on the SF, Horror & Fantasy Box-Office Top 10 of 2001 list).

Trailer here