Mexico. 1973.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Production Design – Alejandro Jodorowsky, Producers – Alejandro Jodorowsky, Allen Klein, Robert Taicher & Roberto Viskin, Photography – Rafael Corteidi, Music – Alejandro Jodorowsky, Don Cherry & Ronald Franjipane, Special Effects – Marcelino Pacheco. Production Company – Abkco Films.

Cast

Alejandro Jodorowsky (The Alchemist), Zamira Saunders (The Written Woman), Juan Ferrara (Mon), Adriana Page (Isla), Burt Kleiner (Klen), Valerie Jodorowsky (Sel), Nicky Nichols (Berg), Richard Rutowski (Axon), Luis Loveli (Lut)

Plot

After being placed on a cross by children and then saved by a legless dwarf, a man wanders through Mexico City where he becomes regarded as a messianic figure. Eventually he passes through a giant chimney into the realm of an alchemist. The alchemist gives the man mystical instruction and then introduces him to eight others from various walks of life. The alchemist tells them of the holy mountain where nine men who have discovered immortality secretly rule the world. It is the alchemist’s intention that he and his recruits will kill the nine masters and take their place. They set out on a journey to the mountain, during which they must undergo mystical understanding in order to complete the task.

For the arthouse vultures who like deranged and strange movies, the poster children are David Lynch and Peter Greenaway. For those who regard Lynch and Greenaway as passe, to be dismissed once the masses have staked a claim, the god that hangs over all weird movies is Alejandro Jodorowsky, a director whose work is so consistently offbeat you can guarantee it will never be claimed by the mainstream.

The personality of Argentinian/Russian Alejandro Jodorowsky himself hangs over and is inseparable from his films – he seems to exude the physical electricity and magnetism of a cult leader, while his biography is impossible to differentiate from self-aggrandising claims. His films are designed not as entertainment but as mystical, transcendental experiences – aptly Jodorowsky casts himself here as a character known as The Alchemist who gives lessons in transcendental thinking (Jodorowsky had originally intended to have his actors hypnotised throughout filming).

Jodorowsky’s mysticism verges on the sometimes purely nonsensical, other times strikingly apt, and is always shocking and violent, not to mention brutally direct in its pragmatism – his solution both here and in El Topo (1970) upon finding the wise masters is to immediately kill them; his advice here to one novice who gets frostbite on the mountain is to cut his fingers off for the sake of the journey. And, as the end of The Holy Mountain indicates, Alejandro Jodorowsky is as much trickster as genuine mystic who could just as easily reveal everything to be a big joke.

El Topo is usually celebrated as Alejandro Jodorowsky’s best work but in truth El Topo is only crude shock theatre tactics with Zen pretensions. At least by the time of The Holy Mountain, which is altogether a better (although generally regarded as a lesser) film, Jodorowsky had polished his pretensions. (With later films, Jodorowsky would abandon mysticism and learn about such things as narrative). The budget allows Jodorowsky wider scope and more lavish lunacy.

What strikes about The Holy Mountain is what a versatile film it is. The first twenty minutes or so could be a reprise of El Topo. These scenes follow a man whose journey becomes a surreal picaresque – we are introduced to him as he is found covered in bees; he makes a recovery after being placed on a cross by children, is saved by a limbless dwarf and wanders through casual vignettes where birds emerge from the wounds of executed victims while the executing soldiers fuck prostitutes while posing for tourist photos; through parades carrying skinned lizards on poles and a recreation of the Spanish Conquest of Mexico with a frog circus; is used as a mold for lifelike Christ statues, which he then smashes up before carrying one through the streets accompanied by a trail of hookers and a monkey.

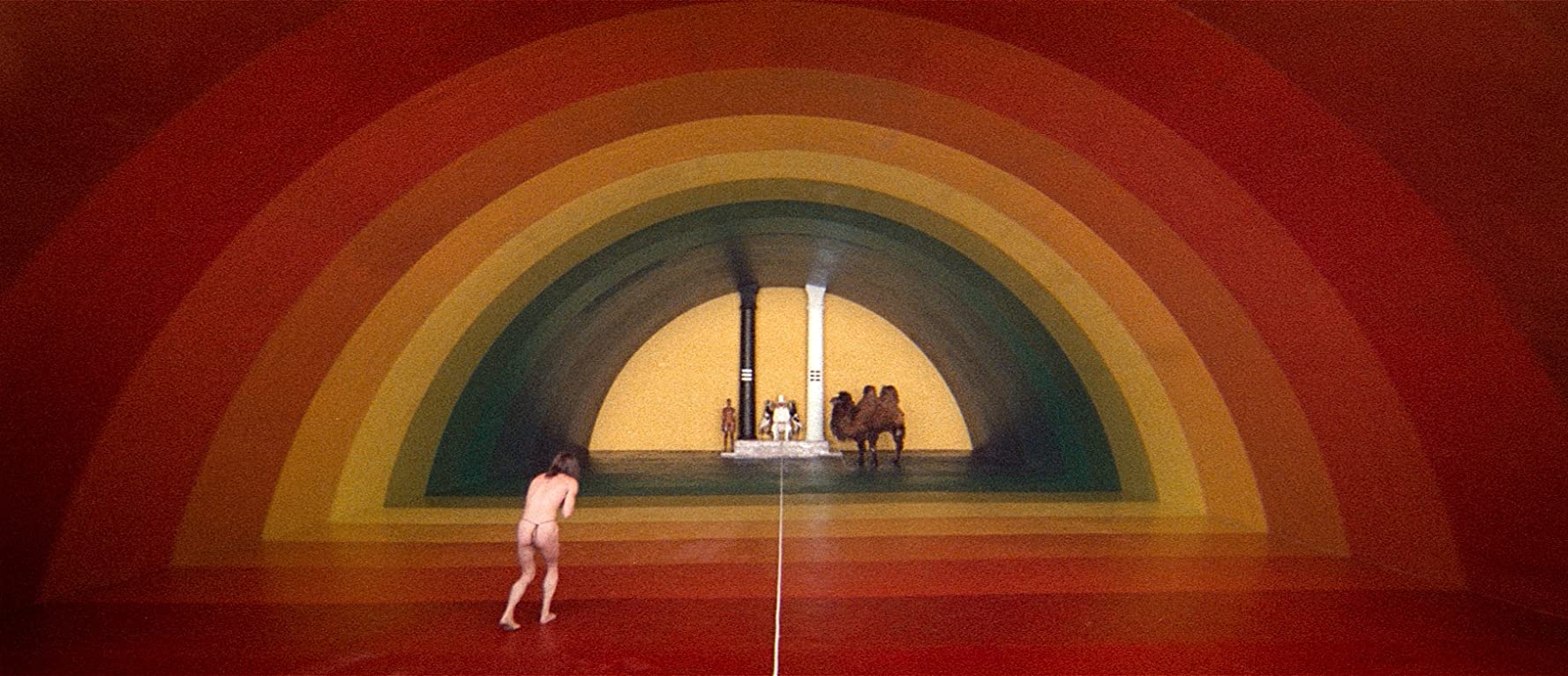

The hero then climbs a smokestack and arrives at The Alchemist’s inner sanctum, whereupon the film becomes something different – what might be described as a mix of Carlos Castaneda and some of Kenneth Anger’s occult film rituals. Having a budget on hand (that came as a result of the cult reception of El Topo) has allowed Jodorowsky to indulge himself and the sets are lush. Jodorowsky himself parades about as The Alchemist, strikingly dressed either in all black or all white with his face hidden by a giant tall peaked sombrero, and surrounded by oxen, hippos, pelicans and a half-naked women with silver fingernail-extensions and cryptic symbols written on her body, as he dispenses Zen-like lessons in eating one’s own shit and breaking a rock by destroying its soul.

Thereafter, as Jodorowsky introduces the postulants and as each gives a potted life history, The Holy Mountain becomes something different again – one where Jodorowsky reveals a heretofore unknown penchant for absurdist comedy. Any of the vignettes could easily have been transplanted into a Monty Python sketch – the blind bed manufacturer who makes business decisions by feeling whether his wife’s sex is wet or not; the weapons manufacturer who produces guns for all creeds – thus crucifix, menorah and Buddha-shaped guns, as well as psychedelic and guitar-shaped guns for youth, plus the wonderfully dotty image of product testers running to impale themselves on bayonets; the manufacturer of facemasks who creates masks that keep moving in the coffin after the wearer’s death – lips that make kissing motions, a cleric’s hand that keeps waving and a pair of rotating breasts; the sex machine – a giant mechanical computer bank that opens up and unfolds and flashes lights as it is titillated with a large rod; and some alarmingly close to the bone satire with the manufacturer of war toys who shows how children are conditioned for a coming war with Peru with war comics that portray Peruvians as villains and a nursery where they are trained to throw mud pies at a picture of a Peruvian.

The last section concerns the journey to the titular mountain with Jodorowsky lecturing the novices on their journey in sometimes striking, sometimes loopy cryptic epigrams:– “I am afraid of heights,” one woman complains to which Jodorowsky’s advice is “Rub your clitoris against the mountain.” The most fascinating aspect is the ending where they reach the top of the mountain only to find that the nine masters are stuffed dummies seated at a table. In the extraordinary final image, Jodorowsky sits laughing with the novices and then says: “Zoom back camera,” which the camera promptly does, revealing the film crew and several camera trestles. “Goodbye Holy Mountain. Real life awaits,” bids Jodorowsky. It is an ending that is both a big shaggy dog joke on the audience and an extraordinary collapsing of the figurative fourth wall.

It is not inapt that Jodorowsky calls himself The Alchemist for that is exactly what his films are – alchemical experiences, theatres of the transcendental. They are experiences where Jodorowsky most fervently wants to upset, jolt and shake up expectations, to break down illusions and leave audiences changed. The ending of The Holy Mountain is an earnest appeal on Jodorowsky’s part for the audience to carry the experience away. Whether Jodorowsky succeeds is a matter for debate, but you cannot deny that he leaves people variously bewildered, amazed, angered, fascinated and stunned by the experience. Which is exactly what he has set out to do.

In an interesting piece of trivia, financing for the film was raised by John Lennon who was an admirer of El Topo. Jodorowsky wanted Lennon to play the central role but Lennon was unable to due to scheduling.

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s other films include Fando and Lis (1968), a surrealistic picaresque; Tusk (1980), about the strange relationship between a woman and an elephant that were born on the same day, which was a financial disaster that has remained unseen outside of France; The Rainbow Thief (1990) about a prince who goes to live in the sewers, which was disowned by Jodorowsky due to interference from producers; and Santa Sangre (1989), a characteristically violent, sexually contorted and over the top tale about a circus performer who acts his mother’s arms (which have been severed by her lover) in a knife-throwing act and is driven to kill women by her domineering personality.

Most recently, Jodorowsky returned with the surreal autobiographical works The Dance of Reality (2013) and Endless Poetry (2016), as well as the documentary Psychomagic: A Healing Art (2019). One of the most fascinating of Jodorowsky’s works was a planned production of Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965) that was announced around 1976 with an amazing cast and production line-up. Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013) is a fascinating documentary made about the failed production.

Trailer here