(Shi Mian Mai Fu)

China/Hong Kong. 2004.

Crew

Director – Zhang Yimou, Screenplay – Zhang Yimou, Li Feng & Wang Bin, Producers – Zhang Yimou & Bill Kong, Photography – Zhao Xiaoding, Music – Shigeru Umebayashi, Visual Effects Supervisor – Angie Lam, Visual Effects – Animal Logic Film (Supervisors – Andy Brown & Kirsty Miller), Digital Pictures Iloura & Mandford Electronic Art and Design Co, Production Design – Huo Tingxiao, Action Director – Tony Ching Siu-Tung. Production Company – Edko Films Ltd/Zhang Yimou Studio/Beijing New Picture Film Co Ltd.

Cast

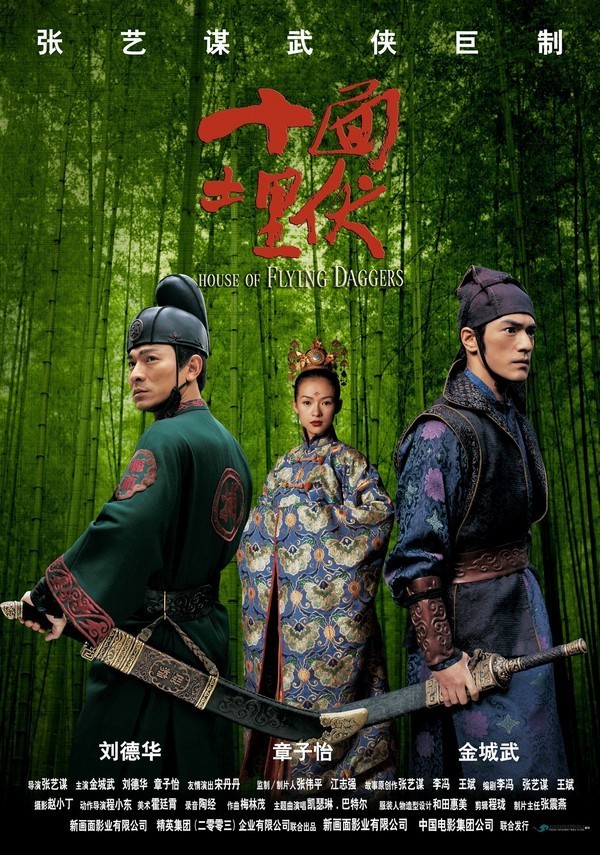

Takeshi Kaneshiro (Captain Jin/Wind), Zhang Ziyi (Mei), Andy Lau (Captain Leo), Song Dandan (Madam Yee)

Plot

The year 859 in the Feng Tian province of China. The Emperor is weak and an organised guild of assassins known as The House of Flying Daggers is plotting his downfall. Two imperial soldiers Jin and Leo follow a rumour that one of the assassins operates in guise as a courtesan at the Peony Pavilion. Jin goes in as a customer and asks to see the best girl, the blind Mei, while Leo then pretends to burst in to stop his boorish behaviour. Mei dazzles Leo with her dance but then tries to kill him. He has her arrested, believing that she is the daughter of the Flying Daggers’ recently assassinated leader, someone who is reputed to be both blind and a martial arts master. Jin pretends to be smitten with Mei and breaks her out of jail and heads north with her as part of a plan to root out the House of Flying Daggers. They are pursued by soldiers who pretend to try and kill them to add conviction to the escape. As they travel, the mission is tested by the inflamed passions between Jin and Mei and then the news that a general has mutinied and has now ordered the pursuing soldiers to kill them for real.

The enormous worldwide success of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) brought about a great interest in Wu Xia cinema, which features a combination of chivalric swordplay and martial arts along with Eastern supernatural elements and casually fantastique moves. Chinese director Zhang Yimou, previously known for sumptuous arthouse films like Red Sorghum (1987) and Raise the Red Lantern (1991), joined the renewed interest in Wu Xia with the extraordinary Hero (2002).

Hero was a film that was made with a spectacular love of the cinema where Zhang Yimou dazzled with the pure beauty of visuals – be it the traditional period settings or the sheer poetry of swordsmen dancing across the tops of lakes. House of Flying Daggers was designed as a companion piece by Zhang Yimou. It featured many of the personnel who were involved in Hero, including lead actress Zhang Ziyi, celebrated action choreographer Ching Siu-Tung, producer Bill Kong and co-writers Li Feng and Wang Bin.

Both Hero and House of Flying Daggers were afforded rapturous acclaim by arthouse audiences upon their appearance in the West, including both being nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards and the Golden Globes. As was the case with Hero, one enjoys House of Flying Daggers for the gorgeous sumptuousness of the visuals that Zhang Yimou throws at us.

The entire film takes places with a dreamy elegance, filled with exquisitely dressed period settings, costumery and gorgeously photographed landscapes dripping with autumnal colours, snow and falling leaves. One reviewer hit the nail on the head when they called Zhang Yimou’s films Wu Xia made in the style of Douglas Sirk, after the legendary expatriate German director who made such Hollywood films as Magnificent Obsession (1954), All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Imitation of Life (1959) where the screen seemed to ooze with the lushness of the Technicolor and dreamy set dressings.

House of Flying Daggers was seen as the slightly lesser sibling of Hero. Hero was filled with dazzling, visually stunning set pieces and Zhang Yimou’s problem with House of Flying Daggers is that while the first film had a newness, House of Flying Daggers comes somewhat in Hero‘s shadow. House of Flying Daggers also takes longer to get to the main story than Hero did. Moreover, House of Flying Daggers is not so much driven by the set-pieces, nor are they quite as rapturously dreamy.

There is even the odd moment – a somewhat over-hyped scene where Takeshi Kaneshiro runs across a field on horseback gathering flowers for Zhang Ziyi – when the set-pieces seem to be trying to be more than they are. Certainly, Zhang Yimou does produce little pieces of mise-en-scene that dazzle with their floridness – the opening scenes with Zhang Ziyi flicking her surplice to beat on drums and then even picking up a sword in the end of it to try and attack Takeshi Kaneshiro; the fights in the forest with Takeshi Kaneshiro firing arrows that simultaneously down four opponents; and the blood-drenched climactic showdown in the snow.

The one sequence that leaps right off the screen is the battle through the bamboo forest with Zhang Ziyi combating an army of soldiers swinging around and bouncing up and down on the trees, she perched halfway between bamboo saplings, fighting swordsmen off with a splintering wooden stake and especially the image of the soldiers flitting through the tops of the trees like phantoms raining down a hail of bamboo spears as Takeshi Kaneshiro and Zhang Ziyi run along the ground.

Zhang Yimou has also borrowed from Japanese samurai cinema the iconic figure of the blind swordsman, made famous through the long running Zatoichi series. (Indeed, Takeshi Kitano had just conducted a remake of the series with Zatoichi (2003) around the same time as Zhang Yimou made these films). Added to this is the traditional melodramatic plotting of Wu Xia – secret societies and clans, love triangles, revelations of elaborate identity masquerades.

Certainly, Zhang Yimou provides us with far more substantial plot than is usually the case in Wu Xia. As in Hero, he gives us an unfolding Chinese Box of a story that opens out multiple times to reveal sudden twists about people’s identities and schemes within schemes. One is not entirely sure if the eventually unveiled plot makes complete sense – I was quite sure in the end why the Flying Daggers needed to lure Jin all the way to their northern provinces – but the larger-than-life melodrama sits perfectly amidst the dreamy visuals.

Zhang Ziyi, who made an astounding debut in Crouching Tiger, and has since become somewhat typecast in these films, is fine – her porcelain features having an ability to radiate both haughty certainty and a tremulously repressed passion. Against her, Taiwanese actor Takeshi Kaneshiro plays with an effortlessly laconic charm.

Zhang Yimou would subsequently return to Chinese dynastic drama with Curse of the Golden Flower (2006), which goes over-the-top with colour and the lushness of set dressings, although unlike Hero and House of Flying Daggers does not contain any fantasy elements. Zhang later returned to fantasy with the English-language The Great Wall (2016) and then made a further Wu Xia drama with Shadow (2018).

(Winner for Best Cinematography, Nominee for Best Director (Zhang Yimou) and Best Actress (Zhang Ziyi) at this site’s Best of 2004 Awards).

Trailer here