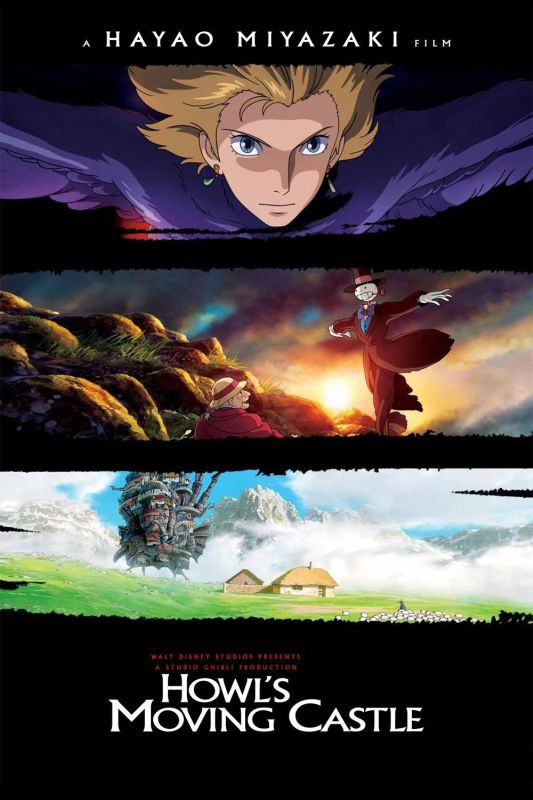

(Hauru no Ugoku Shiro)

Japan. 2004.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Hayao Miyazaki, Based on the Novel by Howl’s Moving Castle (1986) Diana Wynne-Jones, Producer – Toshio Suzuki, Photography – Atsushi Okui, Music – Joe Hisaishi, Animation Supervisors – Takeshi Inamura, Kitaro Kosaka & Akihiro Yamashita, Art Direction – Yozi Takeshige & Noboru Yoshida. Production Company – Studio Ghibli/Dentsu/Nippon Television/Tokuma Shoten.

Plot

Sophie Hatter leads a quiet life working in a milliner’s shop. One day a mystery man asks her to accompany him as the two of them are suddenly pursued by strange blob creatures. The mystery man escapes by flying up into the air with Sophie. Later Sophie receives a visit from the feared Witch of the Waste who places a curse that turns her into an old woman. Horrified at her appearance, Sophie flees into the wilds. Eventually she comes across the ambulatory castle of the feared wizard Howl who is reputed to eat the hearts of maidens. Inside, Sophie meets Howl’s young apprentice Markl and Calcifer, a fire demon that has been imprisoned by Howl to light the hearth and power the castle. She strikes up a deal with Calcifer to find a way to free it in return for it agreeing to restore her youth. She settles in, insisting on doing the cleaning, and is eventually accepted by Howl who turns out to be the mystery man from the alley. She also finds that the front door of the castle opens into different areas of the land, depending on which setting its magic dial is turned to. An invitation comes to Howl for an audience with the king to discuss the war that ravages the land. Howl insists that Sophie go in his place and pretend to be his mother while he accompanies her in shapechanged disguise. The king’s magician Madam Suliman wants Howl, her former apprentice, to come back to fight for the king but Howl refuses. A fierce battle begins as Madam Suliman sends her forces to hunt down Howl. All the while, the warships commanded by both the king and the Witch of Waste ravage the lands.

Japan’s Hayao Miyazaki is almost certainly the greatest animation director in the world. Miyazaki has made extraordinary films such as The Castle of Cagliostro (1980), Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind/Warriors of the Wind (1984), Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) and Porco Rosso (1992). It was not however until recent years with the dazzling likes of Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away (2001), which won the second ever Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, that Hayao Miyazaki’s name came to attention in the West and his films crossed over to be beheld by mainstream audiences. Subsequently, Miyazaki would go onto make Ponyo on a Cliff By the Sea (2008), The Wind Rises (2013) and The Boy and the Heron (2023), as well as to write/plan Arrietty/The Secret World of Arrietty (2010) and From Up on Poppy Hill (2011). The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (2013) is also a documentary about Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli.

Howl’s Moving Castle was Hayao Miyazaki’s ninth film. It is probably not Miyazaki’s best film – it is on the less great side but is still a more amazing film than almost any other animation director’s best. It holds all the regular Miyazaki themes. There is the familiar character of the young girl who wins out through nothing other than her virtue and purity of heart – a character we also see in Nausicaa, My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki and Spirited Away – although here at least Miyazaki has her transformed into an old woman early in the piece. There is the constant fascination with eccentric and archaic flying machines that can be found in almost any Miyazaki film. And there is the recurrent theme of respect for nature – Hayao Miyazaki’s films come filled with beautifully contemplative landscapes and frequently arrive at the realization that peace is found in a respect for and harmony with the natural environment.

Miyazaki adapts the film from Howl’s Moving Castle (1986), a novel by British fantasy writer Diana Wynne-Jones. Miyazaki remains very faithful to the text of the novel, the only major changes being the addition of a war theme that takes over the latter half of the film and takes the story in different directions to the ones that Diana Wynne-Jones did.

There is a sublime and uniquely original imagination to the film – the eccentric image of the title moving castle, which looks like an ambulatory potbelly stove, anthropomorphised with a mouth and tongue, clockwork cogs and even ramshackle cottages hanging off its body; the door that opens into different parts of the world depending on which setting the dial is turned and each emerging out of a perfectly normal doorway where Howl advertises as a different magician; Howl’s bedroom, which is a marvel of dangling lenses, ornate jewellery and clockwork devices.

Most of all, there is Hayao Miyazaki’s penchant for strange and offbeat non-human characters – Turnip, the scarecrow that hops along on a single pole and, though revealing no expression, proves strangely deferential and loyal to Sophie, even in one delightful image hopping along holding a clothesline of washing after him; the terrier dog that plods through the film with thorough indifference; and especially the character of the fire demon Calcifer that powers the castle who gleefully feeds himself logs and lives in terror of the wood going out or Sophie throwing water over him.

Howl’s Moving Castle delights, as all Hayao Miyazaki films do, in its small moments – especially when most of the abovementioned characters are on screen. On the other hand, Howl’s Moving Castle never quite climbs up there into the transcendentally beautiful heights of other Miyazaki films like My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke or Spirited Away. There is never a point where the climax of the film pulls back in a moment of breathtaking awe or a major confrontation, which is something that one almost expects of a Hayao Miyazaki film. If anything, the climax of the film here, involving Sophie somehow travelling back in time or into Howl’s memory, comes out as confusing. Nor do aspects of the wider canvas that Miyazaki casts seem fully satisfactory – the war is left unresolved at the end of the film, even though it forms a major backdrop to the story, while the Witch of the Waste, though cast as the central adversary early on in the piece, is neutralised far too easily and the film continues on without an adequate antagonist.

Maybe this is simply due to the fact that Howl’s Moving Castle was not a project that Hayao Miyazaki was deeply involved in like his other films, rather one that he inherited from another director – Mamoru Hosoda, whose only previous film was as co-director of Digimon: The Movie (2000) but later went onto make The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006), the amazing Summer Wars (2009) and the very Miyazaki-esque Wolf Children (2012) and The Boy and the Beast (2015) – after Hosoda departed over creative differences.

Many of Hayao Miyazaki’s films take place in almost-alternate realities – worlds that seem closely designed on parts of Europe or the Victorian era. Oddly, Howl’s Moving Castle was the second anime film of 2004 to sit in a retro Victorian-era world of Steampunk, coming out two months after Katsuhiro Otomo’s Steamboy (2004). Here Miyazaki chooses an almost-familiar world that seems to be located in late 19th Century Prussia – where a Dickensian Victorian cosiness and Teutonic military uniforms, trains and Steampunk machinery abruptly contrasts with casual use of magic. For a time, this makes you sit astounded, wondering what world the film is taking place in. Like Steamboy, the background of the world is filled with huge ironclad battleships and marvellous flying machines that could have been designed by Albert Robida. Both Howl’s Moving Castle and Steamboy also have strong anti-war and pacifist themes – indeed both films have protagonists caught up in the middle of two warring sides and concluding that war is a bad thing, no matter which side is fighting.

The film is based on a 1986 book by British fantasy writer Diana Wynne Jones (1934-2011), to which she also wrote two sequels. Wynne Jones’ work also served as the basis of Earwig and the Witch (2020) from Miyazaki’s son Goro and also been adapted into the children’s tv mini-series Archer’s Goon (1992).

(Winner for Best Adapted Screenplay at this site’s Best of 2004 Awards).

Trailer here