USA. 1963.

Crew

Director – Don Chaffey, Screenplay – Beverly Cross & Jan Read, Producer – Charles H. Schneer, Photography – Wilkie Cooper, Music – Bernard Herrmann, Stop Motion Animation – Ray Harryhausen, Miniatures – Les Bowie, Production Design – Tony Sarzi Braga, Geoffrey Drake, Jack Maxtead & Herbert Smith. Production Company – Morningside/Worldwide.

Cast

Todd Armstrong (Jason), Nancy Kovack (Medea), Gary Raymond (Acastus), Nigel Green (Hercules), Laurence Naismith (Argus), Douglas Wilmer (King Pelias), Niall MacGinnis (Zeus), Honor Blackman (Hera), Jack Gwillim (King Acetes), Patrick Troughton (Phineas)

Plot

King Pelias invades Thessaly, putting King Arista and his two daughters to the sword. Arista’s son Jason survives and sets out to regain his father’s throne. Because one of Arista’s daughters prayed to Hera before she was killed, Zeus decrees that Hera may come to the aid of Jason – but only five times. Jason decides to go forth on a quest for the Golden Fleece, which has the power to bring peace and rid the land of sickness. With Hera’s help, Jason builds the ship The Argo, holds a Games to select a crew and then sets forth on a journey to the island of Colchis. It becomes a journey through which Jason and his crew encounter many amazing creatures.

Stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen first came to notice in the 1950s, initially with monster movies such as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955) and 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) and then the enormous success of the Arabian Nights fantasy The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). The 7th Voyage of Sinbad was much imitated by other filmmakers and Harryhausen himself returned to the adventures of Sinbad twice in his career.

Ray Harryhausen’s films are largely designed to showcase his stop-motion animated creature effects. Collectively they often seem more like travelogues through a fantasy zoo, with their scripts rarely serving to do more than bring together a menagerie of Harryhausen’s creations. (See below for a complete list of Ray Harryhausen’s films).

Jason and the Argonauts is not any different in this regard. The script takes uneven notice of the original Greek myths. Everything after leaving the Isle of Bronze is basically true to the legend if garbled. Jason’s origin is blurred somewhat – Pelias is supposed to be his uncle, for instance, and there is much that is missing, particularly a good deal of the story’s ambiguity and nastiness. As scripts for Ray Harryhausen films go, this is a little better than most. There is a certain subtext about the fickle, unmerciful fate foisted on Man by the Gods that gives it some resonance.

However, on other levels, the script is prosaic – the Medea romance is flatly introduced and without much ceremony, which leaves little room for the only interesting moment that comes in her character development, when she is asked to choose between Jason and her country, to hinge on. (If Jason and the Argonauts had adhered more to the legend, Medea would have been a far less honourable character – according to the myths she is a sorceress and later in the story murders her own children and then Jason’s bride after he abandons her for another woman).

The ending comes abruptly – King Pelias is still left in power, unvanquished, and without Jason even aware of the identity of his so-called rescuer. Perhaps, Harryhausen and Charles H. Schneer were hoping for a sequel, which never emerged after Jason and the Argonauts met a surprisingly middling box-office performance. Although, Harryhausen and Schneer did later return to the Greek mythological milieu, albeit with a different Greek myth, in Harryhausen’s last film Clash of the Titans (1981).

Don Chaffey’s direction is anonymously clipped. The non-fantastic scenes seem rudimentarily slung together without any dramatic kinesis. Maybe that is why Bernard Herrmann’s score attempts to compensate so much. His is a much celebrated score, but the reason is probably only because it is such a noticeable one – it is loud and inelegant and Herrmann totally overdoes it with thunderous melodramatic brass urgency as though he were trying to drum every moment up to epic size.

The human side of the film also lacks character. Todd Armstrong has a certain swarthy, handsome calibre that is suited to the role – he is stolid but the fault is more a script that doesn’t require him to act. It is also a spic, span and clean an evocation of Ancient Greece – everyone dresses in classical costumes that seem to have come straight from the tailors without a speck of dirt, and everybody over the age of forty gets a dreadfully fake-looking beard. Niall MacGinnis makes for a rolypoly and unintentionally absurd Zeus.

Jason and the Argonauts was almost certainly selected as a property by Ray Harryhausen and Charles Schneer because of the interest in Greek myth that had been sparked by the Italian-made Hercules (1958). This had spawned an entire Italian industry of Hercules and other films (peplum) featuring large musclemen. In contrasting Jason and the Argonauts to these, it immediately becomes apparent why it is such an extraordinary film. Most of these Italian musclemen films are resolutely non-fantastic – featuring at most the odd witch who attempts to seduce Hercules, or the muscleman of the show having to wrestle with a man in a ratty gorilla suit or a dragon. Indeed, the legend of Jason and the Argonauts was previously conducted as a peplum film with The Giants of Thessaly (The Argonauts) (1960), which makes interesting contrast, standing poles apart in terms of quality and imagination.

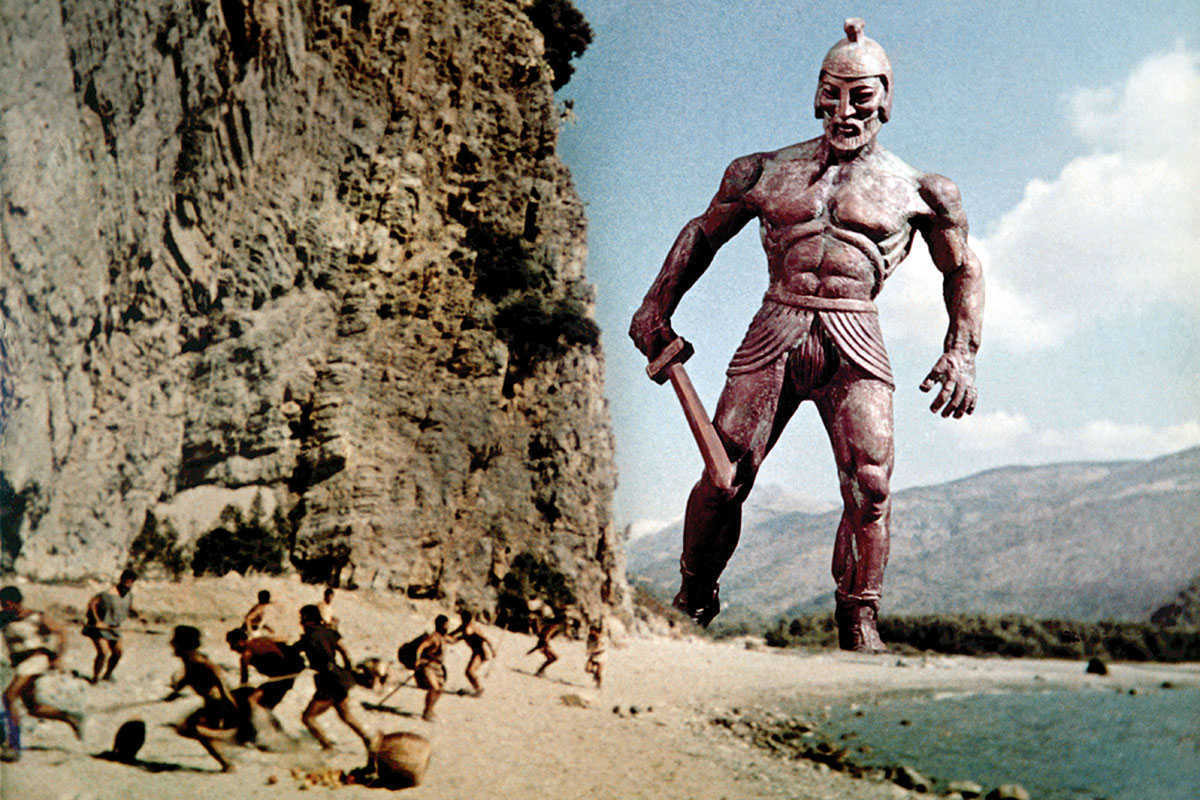

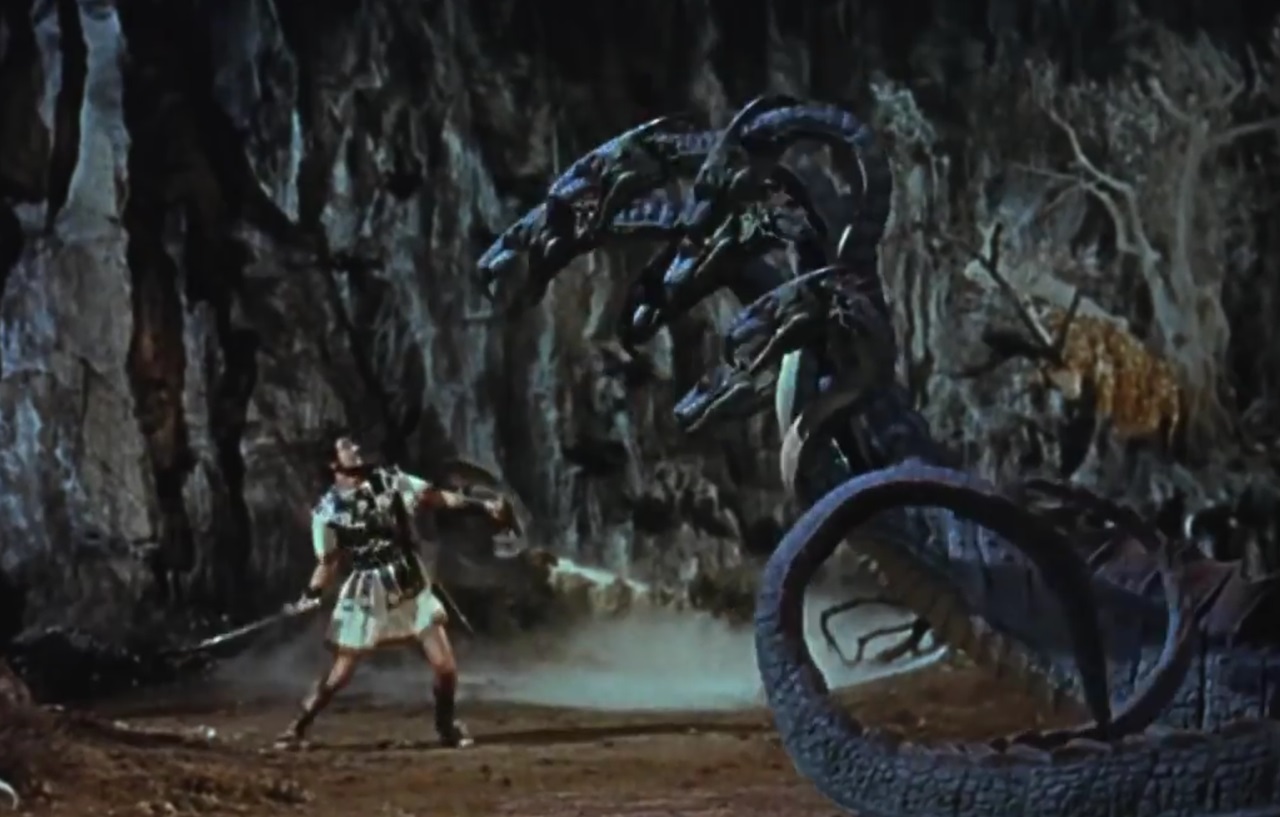

Here the fantastic scenes are mounted with a genuine sense of wonder. Jason and the Argonauts has deservously been called the greatest of all Ray Harryhausen’s films and there is much to justify the case. The scenes with the giant bronze Talos are fabulous, from the moment it slowly turns to look down at Nigel Green, to the race between its legs and Jason’s final unloosening of its bunghole. The sequence with the seven-headed Hydra is also very good, although dramatically the fight seems a little slight.

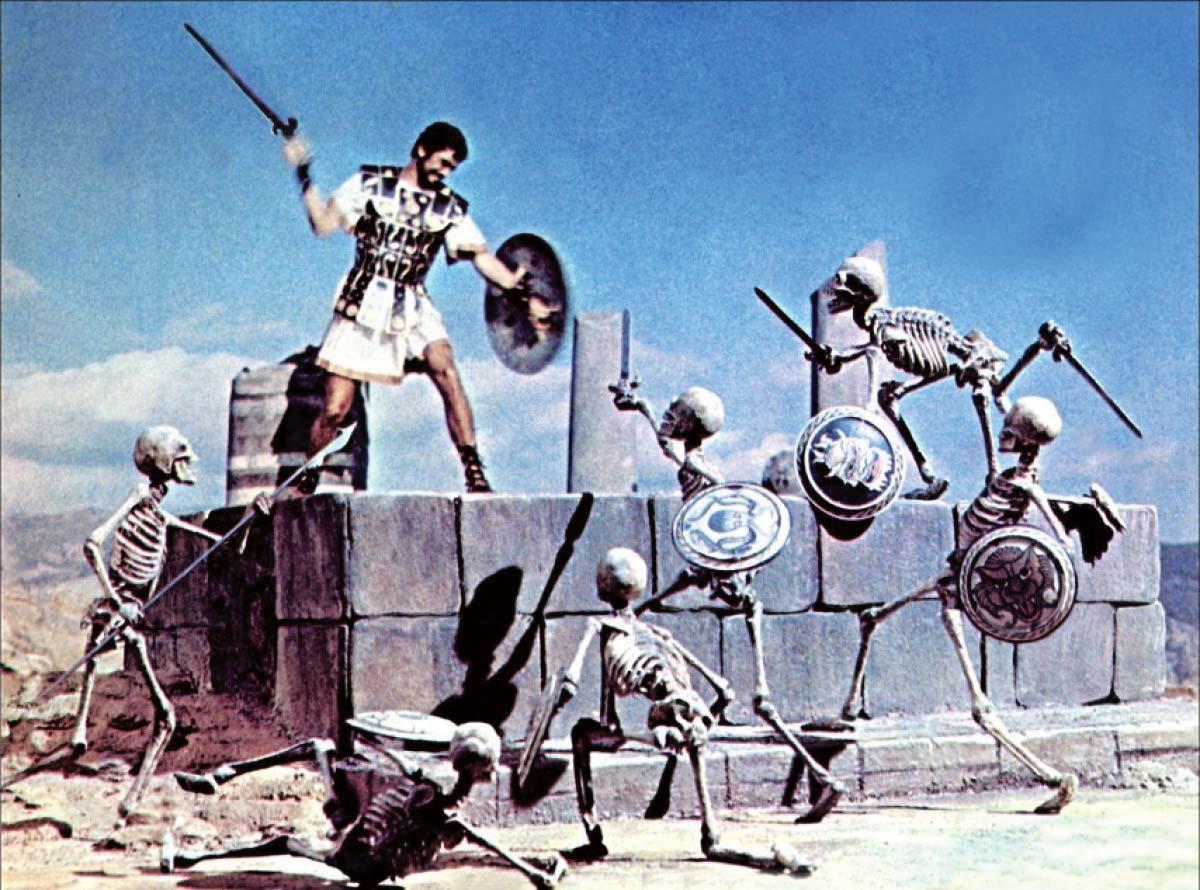

However, the ensuing climactic sequence where Jason must take on sword-wielding skeletons grown from the teeth of the Hydra is brilliant and utterly dazzling in its choreography – Ray Harryhausen manages to invest the skeletons with an indisputable evil in at least one closeup shot on a grinning skull waving the bloody sword that has just killed a man. This is the sort of film that the magic of special effects is all about.

The legend of the Jason and the Argonauts was later remade by Hallmark Entertainment as the mini-series Jason and the Argonauts (2000), which was only a pale shadow of this film.

Ray Harryhausen’s other films are:– The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), the granddaddy of all atomic monster films; the giant atomic octopus film It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955); the alien invader film Earth Vs. The Flying Saucers (1956); the alien monster film 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957); The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958); The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960); the Jules Verne adaptation Mysterious Island (1961); the H.G. Wells adaptation The First Men in the Moon (1964); the caveman vs dinosaurs epic One Million Years B.C. (1966); the dinosaur film The Valley of Gwangi (1969); the two Sinbad sequels The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977); and the Greek myth adventure Clash of the Titans (1981). Ray Harryhausen: Special Effects Titan (2011) was a documentary about his work.

Elsewhere, Don Chaffey made a handful of films during the Anglo-horror cycle, including several for Hammer’s exotica fad with One Million Years B.C. (1966) also for Ray Harryhausen, The Viking Queen (1967) and Creatures the World Forgot (1971). Elsewhere, Don Chaffey directed the psycho-thriller Persecution/The Terror of Sheba (1974). In the 1970s, he moved over to work in US television and also made several children’s films with Disney’s Pete’s Dragon (1977) and the Hanna-Barbera film C.H.O.M.P.S. (1979).

Trailer here