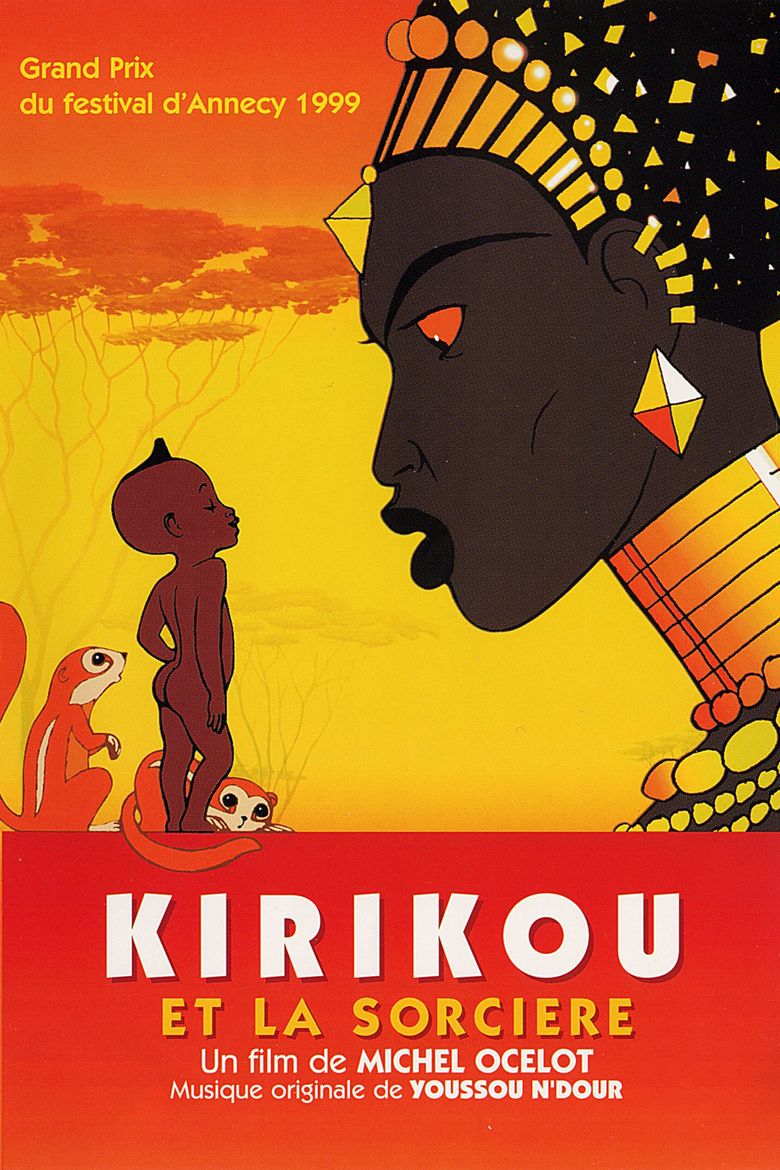

(Kirikou et la Sorcerie)

France/Belgium/Luxembourg. 1998.

Crew

Director – Michel Ocelot, Songs – Youssou N’Dour, Animation – Exist Studio, PTD Tiramasu Studio, Rija Studio, Studio Les Armateurs & Studio ODEC Kids Cartoons. Production Company – Les Armateurs/ODEC Kids Cartoons/Monipoly/France 3 Cinema/R.T.B.F. (Belgian Television)/Studio O/Trans Europe Film/Exposure.

Plot

In an African village, a young boy Kirikou gives birth to himself out of his mother’s womb. Curious as to where the other menfolk in the village have gone, he learns that they have all been eaten by the sorceress Karaba. Kirikou joins his uncle on a journey to confront Karaba, concealing himself inside his uncle’s hat. The sorceress thinks that the hat is magic and agrees to spare Kirkou’s uncle if he will give her the hat. When she learns that she has been tricked, Karaba sends her wooden fetishes to demand all the gold from the women in the village, burning down the house of one woman who tries to hide her jewellery. Kirikou angers the sorceress by asking why she is mean and evil. She sends a canoe and then an ambulatory tree to steal away the village’s children but in both cases Kirikou’s quick witted ingenuity foils her. Kirikou then discovers that the drought in the Cursed Well is due to a creature inside that drinks all the water and so he climbs in and punctures the creature’s stomach. He is drowned as the water is released but is brought back to life by the villagers’ love. He then decides to set forth to meet his grandfather, a wise man who lives on the other side of the mountain, in order to find a means of defeating Karaba. However, Karaba’s fetishes see all that pass the mountain and will try to kill him and Kirkou realises the only way to travel there is to undergo a perilous journey by burrowing underneath the mountain.

Kirikou and the Sorceress was the feature film debut of French animator Michel Ocelot. Ocelot had previously made a number of acclaimed and award-winning animated shorts, although these remain as yet unseen in English-speaking countries. Kirikou and the Sorceress won quite reasonable acclaim on the film festival and arthouse circuit, although had some difficulty obtaining a mainstream America release due to its portrayal of bare-breasted women and the child hero who walks around naked with visible penis.

Kirikou and the Sorceress clearly showed Michel Ocelot as holding the promise of a major new animation talent. He subsequently went on to make Princes and Princesses (1999), an anthology of potted fairytales, the Arabian fairytale Azur and Asmar (2006), the anthology Tales of the Night (2011) and Dilili in Paris (2018), all animated in the same simple line drawn style as Kirikou.

There is an astonishing simplicity to Michel Ocelot’s animation. The characters are all two-dimensional figures drawn in incredibly plain lines and are only ever seen from the side as they move along a two-dimensional horizontal plane. The backgrounds and buildings have a similar bare minimalism, yet also amazingly vibrant colour.

Despite stripping the animation away to next-to-nothing, Kirikou and the Sorceress comes with an enormous strength of story, not to mention a considerable sense of humour. Ocelot is not interested in the cutsie cues of Disney and other children’s animators – there is no touchy-feely sentimentalism, no cute animal sidekicks. This is animation for adults – the story is pitched at a considerable level of maturity (and all in the guise of a children’s film).

The film delights from the very first scene where the young hero calls out from inside his mother’s womb demanding: “Mother, bring me into this world,” only to be told: “A child who can speak from the inside of his mother can bring himself into the world,” whereupon he does. The scenes a few minutes later with Kirikou going to visit the sorceress are hysterical, especially in the images that Ocelot creates of a hat with a pair of feet running away and the wonderfully nonsensical images of the sorceress’s wooden fetishes pursuing (the fetishes prove to be the scene stealers of the show).

The character of Kirikou has a wonderful precociousness – he is really a trickster figure from myth, someone who wins out through a combination of brash curiosity and earnest innocence. There is a lovely scene where Kirikou is drowned after puncturing the water-drinking creature and the whole village comes and starts singing as his mother holds him to her breast and brings him back to life.

Most of the film consists of a series of self-contained stories, although the latter half is taken up by the longer episode of Kirikou’s journey under the mountain to meet his grandfather. This is a charming sequence filled with Kirikou’s encounters with skunks and squirrels, with the squirrels adopting him as their saviour and bringing him gifts, and then helping him avoid the fetishes by disguising him as a bird, only for a cockatoo to take a dislike to him. Ocelot winds the show up with an appealingly left field romantic ending.

There is the feeling throughout that Ocelot is telling a cultural folk myth. The story could be an African folk legend, and many have assumed it was even though the story is one that Ocelot has entirely made up himself. (Ocelot grew up in the former French colony of Guinea in West Africa and almost certainly assimilated much of Kirkou out of native tales and cultural detail).

Kirkou and the Sorceress enjoyed enormous international popularity. Michel Ocelot followed it up with two sequels Kirkou and the Wild Beasts (2005) and Kirikou and the Men and Women (2012), which tells a handful of other tales and allow Ocelot to expand his artwork on a much more expansive canvas. The Kirikou story was later expanded into a stage musical, Kirikou and Karaba (2007), although this has so far not played outside of France.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 1998 list).

Trailer here