Crew

Director/Screenplay – Robert Bresson, Producers – Jean-Pierre Rassam, Francois Rochas & Jean Yanne, Photography – Pasqualino de Santis, Music – Philippe Sarde, Special Effects – Alain Bryce, Production Design – Pierre Charbonnier. Production Company – Mara Films/Laser Productions.

Cast

Luc Simon (Lancelot du Lac), Laura Duke Condominas (Queen Guinevere), Humbert Balsan (Gauvain), Vladimir Antolek-Oresek (The King), Patrick Bernard (Mordred), Arthur De Montalembert (Lionel)

Plot

The Knights of the Round Table return from the quest for the Holy Grail empty handed and disconsolate. Lancelot seeks to recommence his relationship with the Queen Guinevere, but they are torn between their vows of love to one another and the one that Lancelot made to God while on the quest. Unhappy and aimless, the knights take to fighting among themselves. The knight Mordred schemes to bring about Lancelot’s downfall.

French director Robert Bresson (1901-99) is someone who inspires film school and critical theory aficionados to almost rapturous heights of adoration. Bresson is celebrated as one of the influential directors of the French New Wave of the 1960s, although was making films well before this. During his career, Bresson made such works as Angels of Sin (1943), The Ladies of the Bois du Boulougne (1945), Diary of a Country Priest (1950), A Man Escaped (1956), Pickpocket (1959), The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), Mouchette (1967), A Gentle Creature (1969), Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), The Devil Probably (1977) and L’Argent (1983).

Robert Bresson’s works are stripped of contrived dramatics, are about the expressions of inner turmoils and yearnings. His style was minimalist, something that removed all non-essentials from the equation. Bresson even preferred the use of non-professional actors, regarded them as static objects on a stage in the service of his themes – Luc Simon, the lead actor in Lancelot du Lac, for instance, never worked on film again.

I must admit to being one of the naysayers who fail to get Robert Bresson. I am not by any means against films that are not easy to get and have to be interpreted. On the other hand, Bresson’s films feel dull and affectless – the qualities you find in them seem more often to be ones where you have to go and read critical notes and then come back and say “oh yes, that simply wasn’t a dull, static scene, it was one representing an ineffable state of spiritual yearning beyond what could be seen on the screen.” The difference between inner qualities of the spirit invisibly present in a scene and a film that is simply being dull and dramatically inert surely seem like a case of the Emperor’s New Clothes that is dependent on whether or not you chose to impose a certain reading over it.

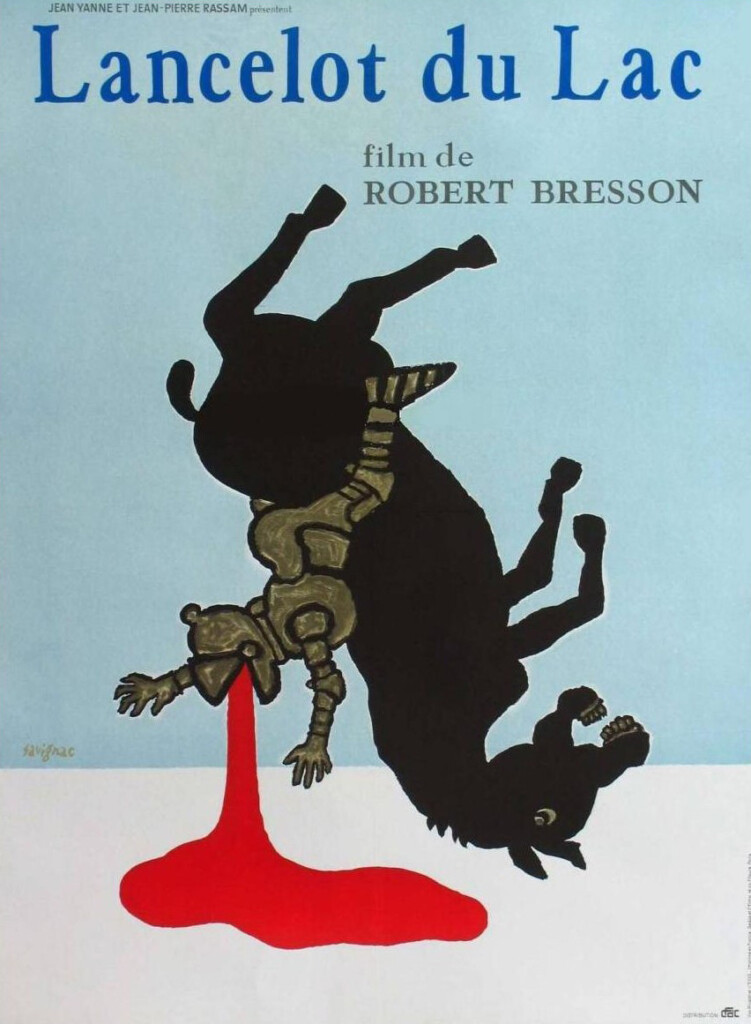

Lancelot du Lac is Robert Bresson’s take on the Arthurian Legends. At the point that Bresson made the film, there was not the major industry of Arthurian fantasies steeped in magic and noble virtues that has grown up since. Screen ventures into the Arthurian legends up to that point had principally been represented by the likes of the Cinemascope spectacular Knights of the Round Table (1954), Disney’s animated The Sword in the Stone (1963) and the ponderous musical Camelot (1967). By the 1970s, the Arthurian cycle had not been discovered by fantasy cinema in a major way so most of these other versions saw it as a stuffy work about knights in pageboy haircuts clanking around in aluminium armour and a certain stiff heroism, or else the romantic silliness of Richard Harris and Vanessa Redgrave singing on swings.

What Robert Bresson gives us with Lancelot du Lac is a version of the Arthurian legends that is stripped of nobility and heroism. The film begins with the knights returning from the Holy Land having failed to find the Holy Grail and the rest of the work deals with that bitterness and loss. Equally, rather than the twee romanticism of Camelot and the expected romance between Lancelot and Guinevere, Bresson gives us two characters tormented and unable to come together by opposing vows they have made. Rather than the nobility of the Knights of the Round Table, we see the knights bickering and scheming amongst themselves, resorting to creating show pageantry because they are bored. In comparison to the subsequent Arthurian fantasies, this is also a version of the cycle that, as you might expect from Robert Bresson, is resolutely grounded in realism and removes Merlin the Magician, Morgan-le-Fay and any display of magic from the telling.

I can kind of appreciate what Robert Bresson is doing here, but I have to say he finds a not terribly interesting way of doing it. The drama in Lancelot du Lac is flat, the characters deliberately blank. It may be that he is communicating some inner spiritual virtue in doing so but I failed to see it; the other side of the coin is that you could also say exactly the same thing about a film that is dull and made with no style.

Bresson is also terrible when it comes to the action scenes. The film opens with a sequence of knights in bloody combat in a forest. The blood looks completely fake and the fight goes on in such an absurdly gory but equally uninvolved way that all you sit doing is comparing it to the encounter with the Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) – indeed, you get the feeling that the Pythons conceived their scene as a parody after watching Lancelot du Lac, which only came out the year before they made their film. Similarly, we get a jousting sequence and a climactic ambush by archers, but Bresson fails to direct these in any dramatic way and simply focuses on the knights pulling down their visors, the legs of the horses and arrows impacting into trees.

Just subsequent to Lancelot du Lac, we had three wildly differing interpretations of the Arthurian legends with Eric Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois (1978), John Boorman’s magnificent Excalibur (1981) and George A. Romero’s modernised Knightriders (1981). Perceval le Gallois was another French New Wave film that sits at diametrically opposite remove to Lancelot du Lac and takes place almost as a work of surrealism amid stylised, unrealistic sets. Boorman bought into the romance and fantasy of the cycle, offering up the definitive screen version, while setting it in a world of grit, blood, armour and magic that was a world away from Knights of the Round Table and Camelot, while Romero offered a vision of contemporary medieval re-enactors jousting on motorcycles and trying to make chivalrous ideals work in the modern world. The French New Wave interpretations are largely forgotten but it is Boorman and Romero’s films that between them created the modern cinematic vision of the Arthurian legends.