Canada/UK. 2012.

Crew

Director/Co-Writer – Deepa Mehta, Screenplay – Salman Rushdie, Based on His Novel, Producer – David Hamilton, Photography – Giles Nuttgens, Music – Nitin Sawhney, Visual Effects – Zoic Studios (Supervisor – Ralph Maiers), Additional Visual Effects – Incessant Rain Studios (Supervisor – Anup Shakya), Special Effects Supervisor – Brock Joliffe, Prosthetic Makeup – Colin Penman, Production Design – Dihip Mehta. Production Company – Hamilton-Mehta Productions/Number 9 Films/Midnight Productions.

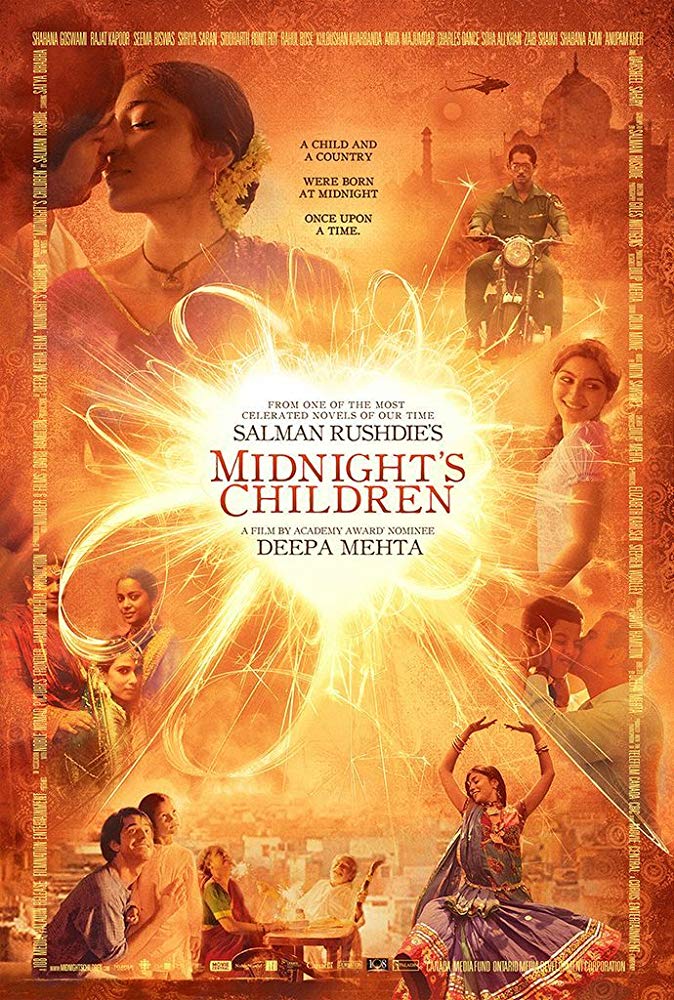

Cast

Satya Babha (Saleem Sinai), Shahana Goswami (Mumtaz Aziz/Amina Sinai), Rajat Kapoor (Aadam Aziz), Ronit Roy (Ahmed Sinai), Seema Biswas (Mary Pereira), Darsheel Safary (10-Year-Old Saleem), Shriya Saran (Parvati), Siddharth (Shiva), Rahul Bose (General Zulfikar), Charles Dance (William Methwold), Zaib Shaikh (Nadir Khan), Kulbushan Kharbanda (Picture Singh), Soha Ali Khan (Jamila Sinai), Anupam Kher (Dr Ghani), Anita Majumdar (Aunt Emerald), Samrat Chakrabarti (Wee Willie Winkie), Shabana Azmi (Older Naseem), Chandan Roy Sanyal (Joseph D’Costa), Sarita Choudhury (Mrs Gandhi), Salman Rushdie (Narrator)

Plot

As India nears independence from British rule in 1947 and the country is to be partitioned into India and Pakistan, Ahmed Sinai and his wife Amina are about to have a child. So too is the poor street busker known as Wee Willie Winkie. The two children are born on the stroke of midnight on August 15th, 1947, the hour of independence. Inspired by her activist boyfriend’s charges that in the new India the rich need to become poor and the poor rich, nurse Mary Pereira switches the two babies in the hospital. Unaware of his low birth, Saleem grows up in the wealthy Sinai household. He discovers he has the ability to summon the voices of all the other children born on the midnight hour, each of whom has unique powers. He names them Midnight’s Children. Shiva, the original Sinai child, becomes harsh and bitter, advocating force and strength. After his true birth is exposed by hospital tests, Saleem is sent to Pakistan to stay with his aunt but becomes embroiled in a military coup. In the subsequent war between India and Pakistan, the Sinai family are killed and Saleem left comatose. Upon recovery several years later, he is reduced to living in the slums. Throughout this, he sees the rise of his rival Shiva to a position of importance in India’s military under Mrs Gandhi’s Prime Ministership. During her suspension of civil liberties, Shiva begins a crackdown against the perceived threat of the Midnight’s Children and their powers.

The name of Salman Rushdie is as much if not even more wound up in controversy than it is in the literary works he has written. Rushdie was born, like the protagonist of the film here, in 1947 (albeit two months earlier than The Partition) to a father who was a Muslim businessman. Rushdie has lived most of his life outside of India (in the UK and US) after leaving to study at Cambridge. He began publishing with the novel Grimus (1975) but it was his second book Midnight’s Children (1981) that gained him major attention as a writer. The book won that year’s Booker Prize and has been celebrated on several lists as one of the great literary works of the 20th Century.

The one work that Rushdie will always be associated with however is his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses (1988), a complex interwoven narrative in which two people are inhabited by angelic entities out of Islamic mythology. The controversy over the book is due to Rushdie’s wilfully irreverent portrayal of the life of the prophet Muhammed. This caused widespread protest in the Islamic world, even riots in some countries. The controversy was heightened when Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeni passed a fatwah against Rushdie in 1989 – an edict calling on all Muslim persons to kill Rushdie. Rushdie has never been harmed, although two translators of the book have been targeted, and he has been forced to spending a good deal of his time in hiding and under police protection.

There is no doubt that Salman Rushdie is an exceptional literary figure and the lengthy list of awards, knighthoods and honorary professorships he has accrued bears testament to this. One of the least things that Rushie is celebrated as is a fantasy writer – although he does receive an entry in the estimable The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1992) by John Clute and John Grant. Almost all of his works touch base with genre fantasy in some way – Grimus is a book about a potion of immortality; The Satanic Verses features figures Islamic angels and devils; Shame (1983) and The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995) are steeped in Magical Realism; The Enchantress of Florence (2008) is a series of interwoven fantasy and historical stories; The Ground Beneath Her Wings (1999) is a modern variation on the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice; while he has also written two overtly fantastical children’s stories with Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990) and Luka and the Fire of Life (2010). Rushdie has even written an entire non-fiction analytic work about The Wizard of Oz (1939). However, the fans of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling are certainly a world apart in terms of reading bracket from those who pick up the works of Salman Rushdie.

Midnight’s Children is the first of Rushdie’s works to be adapted to the screen. He has entrusted this to the hands of Deepa Mehta, an expatriate Indian director who has resided in Canada since the 1970s. There she has gained critical acclaim as a director with her trilogy of films Fire (1996), Earth (1998) and Water (2005), along with other works such as Bollywood/Hollywood (2002) and Heaven on Earth (2008). She has even directed episodes of the tv series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992).

Midnight’s Children is essentially a variation on Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper (1881), although one where Rushdie has little interest (at least in the film version) of showing the poor Shiva’s life as compared to Saleem’s – in the film, Shiva exists as no more than a shadowy nemesis. The great concern for Rushdie is how the interlinked fate of the two children serves to wind the larger backdrop of a history of late 20th Century India.

Through a convoluted (but never difficult to follow) series of contrivations, the film follows such key dramatic events as the Partition of India in 1947 (whereby the country was controversially divided into territories along religious lines and rule handed back to India from the British Empire), the military coup by General Ayub Khan in Pakistan in 1958 and the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 that ended with the formation of Bangladesh. The particular focus that Rushdie saves his anger for is Indira Gandhi and her decree of military rule between 1975-7 (after a controversial court decision that deemed her election as invalid due to electoral malpractice), as well as her order for the demolition of the slums in areas of Delhi in 1976.

This is perhaps the story that most of the arthouse crowds are going to see with Midnight’s Children. There is however another entire fantasy film that nests inside that. In actuality, you could call Midnight’s Children an Indian version of X-Men (2000) – albeit crossbred with the Magical Realist cross-generational family saga of something like The House of the Spirits (1993).

Or perhaps even more so than X-Men you could aliken the film to Watchmen (2009), which took a classic superhero tale and wove it in and around key historical events of the 20th Century. As opposed to Watchmen, which more accurately emerges as an alternate history, Midnight’s Children is more of a secret history that offers not an alternate version of historical events but an alternate interpretation of existing historical events – like where we learn that the real reason for much of Mrs Gandhi’s assumption of power was to deal with potential threat of the Midnight’s Children and the reason for the demolition of the Jama Masjid slums and subsequent sterilisations of its people was to root out and stop the Children.

You can see what a comic-book superhero saga could been drawn out of this – children who are each granted unique powers due to being born at a magical hour, the hero having an ability to draw them together in a congress, the epic battle between good and evil as two of the personalities seek to influence the outcome of a country. Certainly, Midnight’s Children plays this out differently than a superhero film would.

A superhero film would probably not concern itself with the extended family saga dealing with Saleem’s parents and grandparents that takes up the first three-quarters of an hour (although is something necessary to set the film’s stage). It would also have placed more focus on the Midnight’s Children and had more in the way of exploration of their powers and scenes showing them in usage (Deepa Mehta is very sparing when it comes to special effects). Saleem and Shiva would have been caricatured more as superhero and super-villain with Parvati as a love interest caught between the two. The film sort of conducts an epic showdown between the two towards the end but a superhero film would almost certainly have pitted them together in actual combat.

Certainly, Rushdie and Deepa Mehta’s is not an uninteresting telling and the film tells everything against an epic and beautifully filmed canvas. Rushdie (who also narrates the film) largely takes a modest backseat – the mirthful intellectual play that his dialogue has on the page is far more subdued up on screen – mostly he sits back and allows Deepa Mehta to interpret the story visually. Great and acclaimed books don’t necessarily translate to great and acclaimed films. While the written version of Midnight’s Children was lavished with book of the century plaudits, the film version falls short of such stature. Still, it is a worthwhile and enjoyable ride.

Perhaps the oddest aspect of the film is that it is an intimate story about India yet is financed by Canadian and British money, made by Indians who live outside of India and not even filmed inside India but neighbouring Sri Lanka. (The reason would appear to be that Sri Lanka has far less of an Islamic population than India and the production team were seeking to avoid the controversy associated with the Rushdie name – an earlier proposed British mini-series adaptation of Midnight’s Children was shut down in the UK because of religious protests. This production was even shot under a different title to keep people away).

Whether this leads to a less authentically Indian film is perhaps something that only someone more familiar with the culture than I could tell. What it does do however is add up to a more open film than you suspect would have been made within India. While India readily regards such things as the depiction of kissing as taboo, this film has no such qualms and even offers up naked breasts. More crucially, Bollywood cinema is aimed at a more populist market with its songs and obligatory colourful dance numbers. With exceptions, Bollywood is largely not a genre that has managed to produce many works that aim beyond populism or discover greater literary ambitions, let alone are brave enough to tackle dealing with the country’s controversial and chequered history.

Trailer here