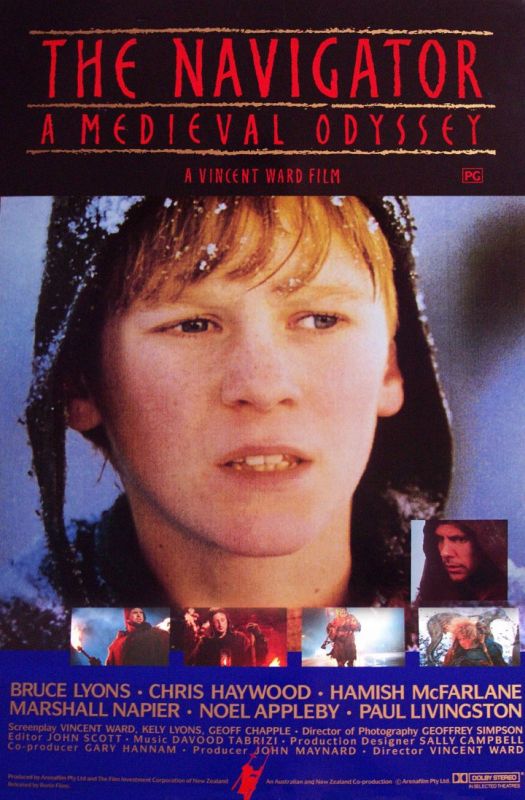

aka The Navigator: An Odyssey Across Time

New Zealand/Australia. 1988.

Crew

Director/Story – Vincent Ward, Screenplay – Vincent Ward, Geoff Chapple & Kelly Lyons, Producer – John Maynard, Photography (b&w + colour) – Geoffrey Simpson, Music – Davood Tabrizi, Production Design – Sally Campbell. Production Company – Arena Films/Film Investment Corp NZ.

Cast

Hamish MacFarlane (Griffin), Bruce Lyons (Connor), Marshall Napier (Searle), Noel Appleby (Ulf), Chris Haywood (Arno), Paul Livingston (Martin), Desmond Kelly (Smithy)

Plot

The year 1348 in a small village in Cumbria that is besieged from the outside world by carriers of the Black Death. Young Griffin has a vision that the plague will pass the village over if the villagers make a pilgrimage to carry a cross to a city of lights and mount it on a cathedral before dawn rises. Led by Griffin’s visions, a group of miners tunnel down to the centre of the earth and emerge out into modern day Auckland, New Zealand. They find this new world frightening and wholly bewildering. As they search for the cathedral, Griffin has a vision that one of them will also die before dawn.

If there is ever a list of directors who make far too few films then the name of Vincent Ward must surely sit at the top of the list. Vincent Ward is one of the most exquisitely painterly of all directors. He crafts entire films with painstaking minutiae to detail and the play of light like some Flemish master. Ward was born in New Zealand and first impressed with two celebrated but nowadays impossible to find shorts, A State of Siege (1978) and the documentary In Spring One Plants Alone (1981), before emerging onto cinema screens with the feature-length Vigil (1985). Vigil is a complex, beautiful film that almost entirely sidesteps narrative for a striking series of primal moods and images, all entirely about the play of light, mud and the Earth.

The Navigator: A Mediaeval Odyssey was Vincent Ward’s second film and is a concession to more commercial filmmaking, particularly in areas like plot, although is no less beautiful a film than Vigil. The Navigator received a rapturous response at various international film festival screenings – indeed, it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes that year – and had Vincent Ward’s star touted in Hollywood. It led to Ward being offered the opportunity to helm several mainstream productions, including The Neverending Story II: The Next Chapter (1990) and RoboCop 2 (1990).

Ward subsequently became one of the numerous directors attached to the development revolving door that was Alien3 (1992), where he came up with a mind-boggling scenario that wound in monks, a wooden planet and saw the alien as fulfilment of various religious prophecies, although he eventually only ended up with story credit on a muchly watered down version of his vision. Subsequently, Ward bummed around Hollywood directing commercials to make ends meet. He was attached to a fascinating sounding version of the epic legend Beowulf at one point but could not find the financing and later developed The Last Samurai (2003) but saw it taken over by another director.

He did manage to get the Inuit romance Map of the Human Heart (1992) off the ground, which proved a glacial and distant film that left audiences disappointed on the promise that Ward was seen as holding as a result of The Navigator – although the film does have a stunning vision of the Wartime Blitz of London that is pure Ward. Ward recovered with the amazing afterlife fantasy What Dreams May Come (1998), wherein the employment of modern CGI effects literally allowed him to craft three-dimensional realizations of classical works of art. Subsequently, Ward returned to New Zealand to make the deeply troubled River Queen (2005), a drama set during the Maori Wars, and the quasi-documentary Rain of the Children (2008) about a Maori curse.

The Navigator: A Mediaeval Odyssey came out amidst the renaissance and maturation of time travel films that followed the successes of The Terminator (1984) and Back to the Future (1985). What is noticeable about comparison between The Navigator and these other films is the backgrounds that their respective directors draw upon. With The Terminator, James Cameron draws upon a love of science-fiction literature; in Back to the Future, Robert Zemeckis draws upon a childhood love of screen science-fiction. By contrast Vincent Ward comes from a formal arts background and draws upon a love of Mediaeval art. The focus of the films is entirely different – The Terminator is a pounding powerhouse of an action film where James Cameron conducts an adept twist on classical time paradox; Back to the Future is at heart a pop culture fantasy about being able to meet one’s parents and shake up their squareness. By contrast with The Navigator, Ward leaves barrelling action and feelgood Me Generation reconciliations far behind to construct a dark vision of a completely alien modern world as seen through the eyes of uncomprehending Mediaevals. The results are utterly striking and The Navigator is certainly one of the most mature and complex films to emerge from the 1980s cinematic time travel cycle.

The story and characters are thinly sketched. The “it was all a dream” twist ending seems frustrating in that the modern world that we see seems far too familiar to be passed off as merely a dream. The metaphors that Ward, in an interview with the author, said that his odyssey stands for – the Black Plague for AIDS; besieged Cumbria for nuclear-free New Zealand – have a certain earnest naiveté.

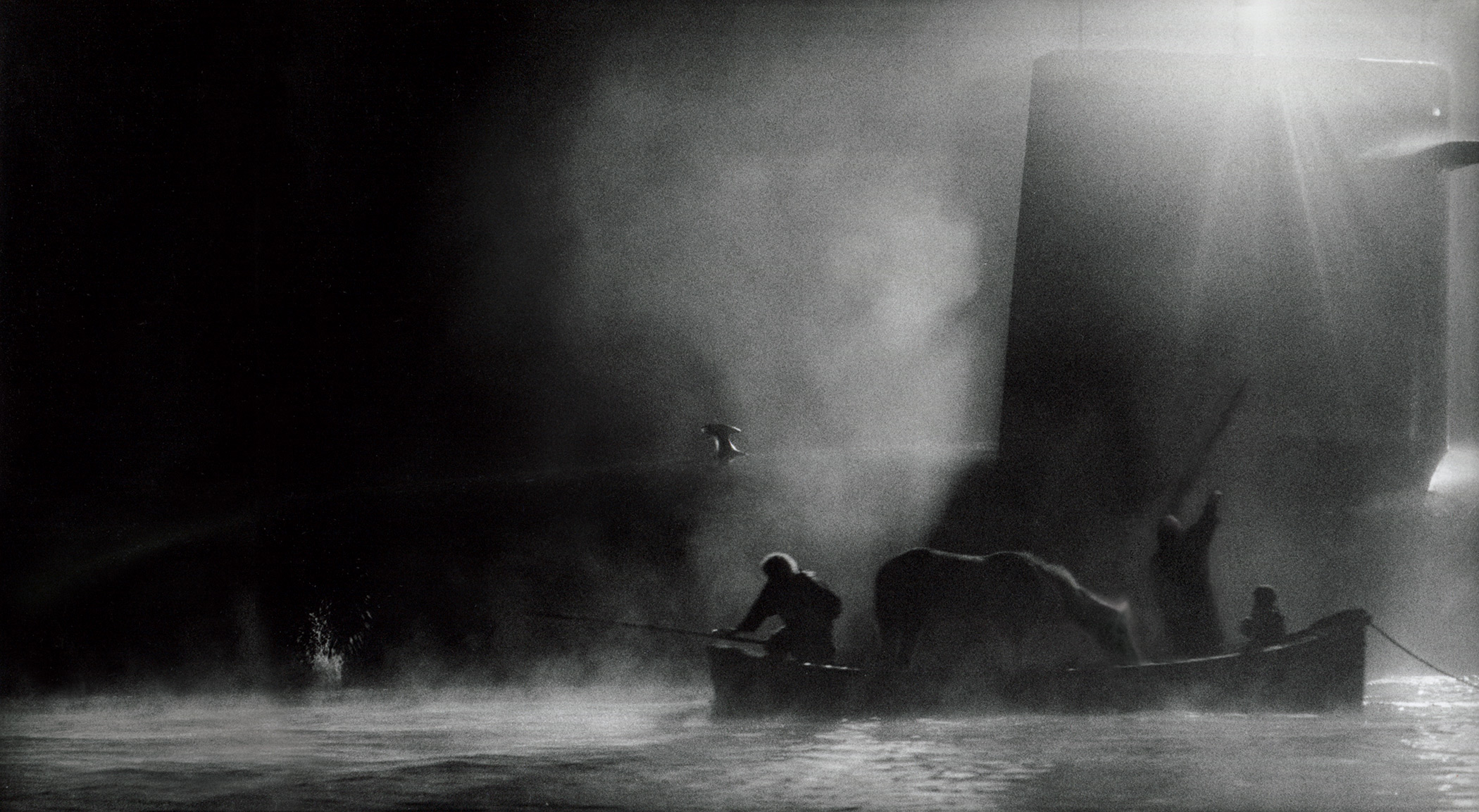

Nevertheless, The Navigator is still a Vincent Ward film and is something that moves on a subliminal level of painterly – in this case Baroque – tableaux. The images that Ward creates – visions of giant winged skeletons flying across gibbous moons – are arrestingly intense, almost hallucinatory in beauty. Most striking are the confrontations with the modern world that take on a primal nightmare quality as seen through the eyes of the Mediaevals – a submarine (which improbably surfaces in Auckland Harbour) taken for a sea-monster and the images of the Mediaevals pitifully battering against it; trucks in a junkyard and cranes with grasping claws taking on the appearance of looming gargantua; Griffin confronting the multiple images of a personified Death reflected across the banks of a storefront window of tvs in an AIDS commercial; even the terrifying problems presented in simply crossing the street.

The film is utterly fascinating, as if Vincent Ward has drawn one into something that has the clarity of a wide-awake dream. Vincent Ward is an extraordinary artist. The Navigator is stunningly photographed in both colour and black-and-white – some of the compositions of light and darkness that the film offers make one cry out in surprise – like the still, eerily lit image of Hamish MacFarlane running down an empty street pursued by Marshall Napier on a horse. Ward also made a painstaking effort to have the cast speak with authentic Cumbrian accents. There is also an exceptional eerily atonal score.

Trailer here