Crew

Director – Harold S. Bucquet, Screenplay – Alice D.G. Miller, Frank O’Neill & Claudine West, Based on the Play by Paul Osborn of the Novel by Lawrence Edward Watkin, Producer – Sidney Franklin, Photography (b&w) – Joseph Ruttenberg, Music – Franz Waxman, Art Direction – Cedric Gibbons. Production Company – MGM.

Cast

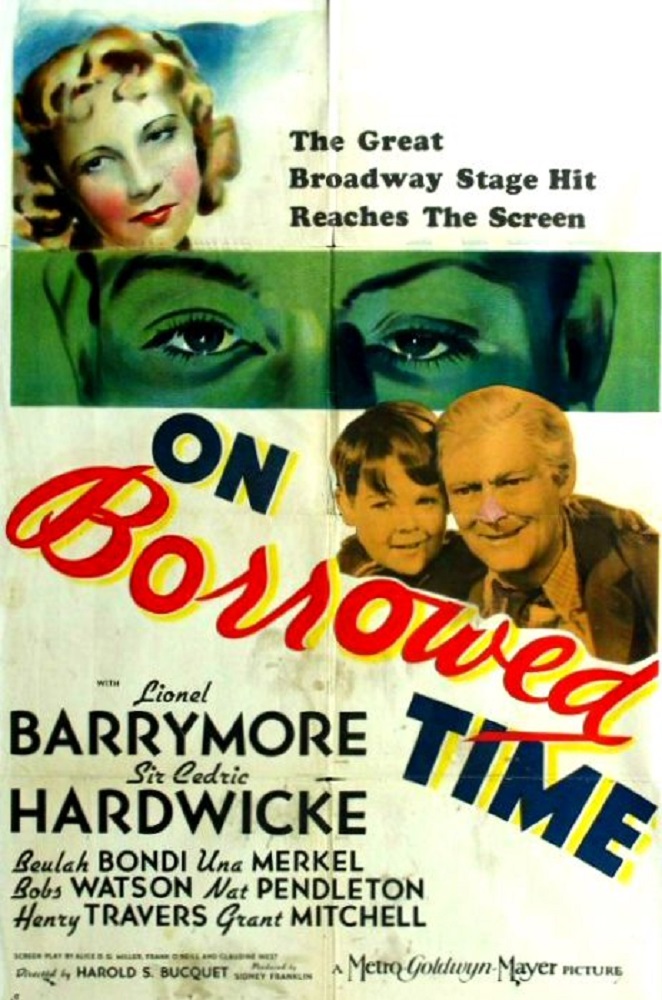

Lionel Barrymore (Julian Northrup), Bobs Watson (John ‘Pud’ Northrup), Sir Cedric Hardwicke (Mr Brink), Eily Malyon (Demetria Riffle), Beulah Bondi (Nellie Northrup), Henry Travers (Dr James Evans), Una Merkel (Marcia Giles), Nat Pendleton (Mr Grimes)

Plot

Aging, wheelchair-ridden Julian Northrup and his wife Nellie have custody of his grandson Pud. After Nellie dies, Julian has to face the efforts of Nellie’s shrewish sister Demetria Riffle to gain custody of Pud. Mr Brink, the angel of death, then appears to take Julian. Instead, Julian tricks Brink into picking an apple from the tree in his yard and then traps him up there. When Julian starts talking about Mr Brink, who nobody else is able to see, Demetria seizes upon the opportunity to have him declared insane. However, with Brink trapped in the tree, nobody else in the world is able to die except when they touch the tree, and the cunning Julian uses this to his advantage. As others discover what has happened, they try to persuade Julian to free Mr Brink and restore Death, but this mean he will have to allow himself to be taken.

On Borrowed Time is an interesting variation on the afterlife fantasies that came from the Wartime era, a period when such films were at their height. There are many similarities between this and that other classic produced a few years earlier, Death Takes a Holiday (1934). Both are adapted from stage plays and both feature an incarnate Death. In fact, On Borrowed Time could have been expanded from out of one of the ideas that featured in the background of Death Takes a Holiday – the idea that while Death is present on Earth all mortality is held in suspension. Both films also portray Death as a decent figure – here Death waits for people to finish what they are doing before claiming them, something you cannot help but compare to various accounts of less than dignified death in real life.

It is worth comparing both films to the afterlife fantasies of the 1940s that emerged following the US entry into WWII – the likes of Here Comes Mr Jordan (1941) and A Guy Named Joe (1943). Death Takes a Holiday and On Borrowed Time seem to hold the view that Death is a matter of people genteelly learning to accept the natural processes of life, whereas the films of the 1940s by comparison seem almost hysteric in the need to prove to people the existence of an afterlife in defiance of true (Wartime) tragedy.

The film itself is slow, talky and stagy. It is directed with little style, it is merely a dramatisation of a play. Without good actors giving it life, it would be considerably less than it is. Nevertheless, when the drama kicks in, it certainly becomes interesting and the plot takes a series of wild lurches and turns that are positively ingenious at times. There does remain one plausibility hole at the centre of the film – and that is that it never clearly establishes how come Death gets caught climbing into the tree and what it is that prevents him from merely jumping down when it seems he could easily do so. You sort of have to ignore this.

That said, the point that the film gets Death up into the tree, is the point that the film starts to gets interesting, spinning the story through a fascinating series of conundrums to the point where Lionel Barrymore faces the choice of either letting Death loose or losing the custody of his son. Barrymore shows great blarney and holds the screen in particular during one scene where he forces Demetria and the sheriff to back down by threatening to take them with him.