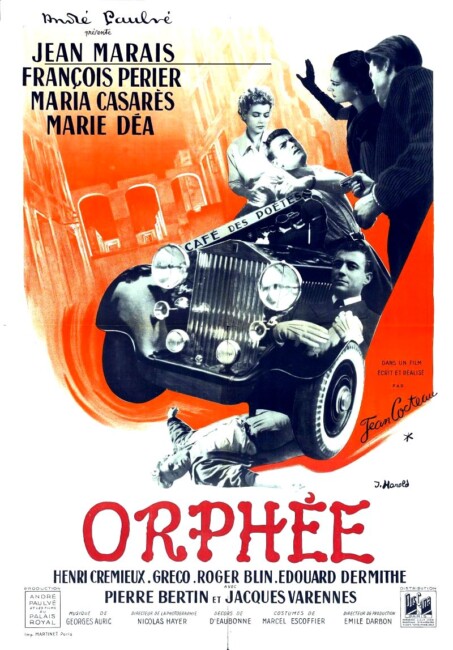

(Orpheus)

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Jean Cocteau, Producer – Andre Paulve, Photography (b&w) – Nicolas Hayer, Music – Georges Auric, Art Direction – Jean d’Eaubonne. Production Company – Andre Paulve/Films du Palais-Royal.

Cast

Jean Marais (Orphee), Francois Perier (Heurtebise), Maria Casares (La Princesse), Maria Dea (Eurydice), Edouard Dermithe (Cegeste), Juliette Greco (Agalonice)

Plot

The poet Orpheus is witness as two motorcycle riders run down his friend, the poet Cegeste, at a cafe. A mystery woman, The Princess, offers to take Cegeste’s body to the police and asks Orpheus to accompany her as a witness. Instead, The Princess takes the body to a country mansion where Orpheus watches her raise Cegeste from the dead and then disappear through a mirror with him into the Land of Death. Orpheus becomes obsessed with The Princess and preoccupied with listening to the limousine radio through which he can pick up random snippets of Cegeste’s poems. In his obsession, Orpheus neglects his wife Eurydice whose life is then claimed by The Princess. And so Orpheus ventures through a mirror into Hell to profess his love for The Princess.

Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) is one of the more interesting figures in French cinema. In the time between the two World Wars, Cocteau earned his reputation as a novelist, poet and playwright, publishing his first book of poetry when he was only 16 years old. During the 1920s and 30s, Cocteau created works in collaboration with luminaries such as Pablo Picasso and Igor Stravinsky. Many of Jean Cocteau’s works circle around traditional myths – such as the ballet Oedipus Rex (1927), which translated Oedipus Rex, the play The Infernal Machine (1934), which offered a modernised updating of the same, and the self-explanatory The Knights of the Round Table (1937), as well as an earlier stage version of Orphee (1926).

However, it has primarily been for his films that Jean Cocteau has become known. Cocteau’s first film script was L’Eternal Retour (1943), an updating of the legend of Tristan and Isolde for director Jean Delannoy. He made his own directorial debut with the surrealist short The Blood of a Poet (1930) but his full-length debut came with the stunning fairy-tale adaptation Beauty and the Beast (1946), which is still the definitive version of the tale, and was the film that consolidated Cocteau’s reputation internationally.

Orphee was Jean Cocteau’s fifth film. Rather than a classical retelling of the myth, as he attempted with Beauty and the Beast, here Cocteau updates and modernises the Greek legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. He certainly expands the story over the Greek original – there is no equivalent of the Princess in the Greek myth, for example. Indeed here, the figure of Eurydice, whom traditionally Orpheus descends into the underworld to win back, is almost an irrelevant character, Orpheus is instead romantically obsessed with the Princess; and when Orpheus and Eurydice are sent back it is not because of his undying love for her but because the tribunal decides they do not belong in the afterlife.

There is much that is autobiographical to the film – Cocteau was an acclaimed and influential poet in the Wartime era but who then was savaged by the new generation that emerged following the War, as Orpheus is here. The actor that Cocteau casts as Orpheus, Jean Marais, was Cocteau’s gay lover, which offers unusual resonance to the melancholy love story. Elsewhere, the milieu that Cocteau gives the legend unmistakably resonates with the shadow of post-War France – Hell is an area of bombed cityscape, the afterlife tribunals echo with images of the trials of Vichy collaborators, while the image of Orpheus seeking messages hidden inside random radio noise looks back to images of the French resistance obtaining code messages from the British hidden inside standard radio broadcasts.

There is an elegant intellect in some of the ideas and metaphors that Jean Cocteau swings – like the mirror being the interface to the Land of the Dead because it always shows the path of oncoming age, or the intriguing idea that those that rule the afterlife are only pawns in a game that nobody runs. The modernisation of the myth is conducted with a certain degree of wit – Orpheus’s final glance back at Eurydice takes place in the rear vision mirror of a limousine, for instance; while The Bacchantes (the Thracian women who killed Orpheus according to legend) is the name of a nightclub.

Far more so than in the fairy-tale simplicity of Beauty and the Beast, Jean Cocteau taps into the French post-war existential cinema. Typical of the film’s intellectual posturing is a scene where a much-acclaimed work of poetry is revealed as a book with blank pages. The dialogue is full of the banal exchanges that suffer as significance in these films.

Mostly though, Cocteau impresses with the sheer poetry of his images – the path through the underworld (a ruined city that is lit to seem unworldly) and the slow-motion fight with the spectral wind, or the final images as Orpheus is taken away by a motorcycle escort of angels and the Princess is led off to her fate, or the simple reverse motion effects that Cocteau uses to show the passage through the mirror. It is rare that French cinema impresses with visual imagery – but Orpheus does.

Jean Cocteau later made The Testament of Orpheus (1960), which is not a sequel but an existential meta-fictional autobiography upon Cocteau’s part, which does wind in many of the characters and images from Orpheus.