USA. 2003.

Crew

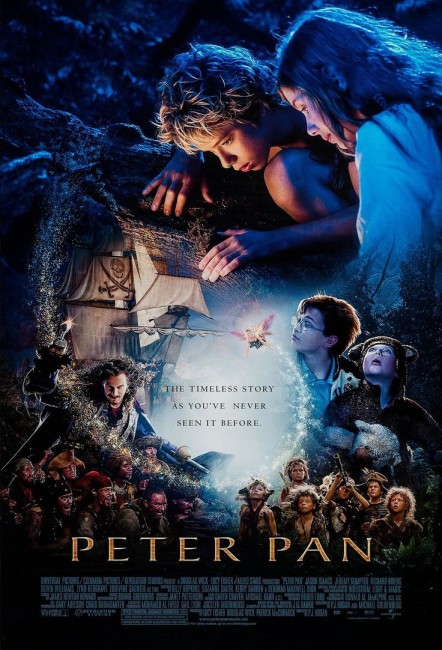

Director – P.J. Hogan, Screenplay – P.J. Hogan & Michael Goldenberg, Based on the Play and Novel by J.M. Barrie, Producers – Lucy Fisher, Patrick McCormick & Douglas Wick, Photography – Donald McAlpine, Music – James Newton Howard, Visual Effects Supervisor – Scott Farrar, Animation Supervisor – Jenn Emberly, Pre-Visualization Supervisor – David Dorovetz, Visual Effects – Digital Domain (Supervisor – Mark O. Forker), Industrial Light and Magic & Sony Pictures Imageworks (Supervisor – Mark Stetson), Pacific Title and Digital, Photon & R!ot, Special Effects Supervisor – Clayton W. Pinney, Creature Effects – John Cox’s Creature Workshop, Animatronic Crocodile – WETA Workshop, Production Design – Roger Ford. Production Company – Universal/Columbia/Revolution Studios/Allied Star

Cast

Rachel Hurd-Wood (Wendy Darling), Jeremy Sumpter (Peter Pan), Jason Isaacs (Captain James Hook/George Darling), Ludivine Sagnier (Tinkerbell), Lynn Redgrave (Aunt Millicent), Olivia Williams (Mary Darling), Richard Briers (Smee), Harry Newell (John Darling), Freddie Popplewell (Michael Darling), Geoffrey Palmer (Sir Edward Quiller Couch), Carsen Gray (Princess Tiger Lily)

Plot

In turn of the 20th Century London, Wendy Darling and her two brothers love playing make-believe adventures of pirates. Wendy’s Aunt Millicent tells her that she must learn to grow up and be a lady and that her father must become a man of proper station. Wendy’s bedroom is then invaded by a flying boy Peter Pan who has come in search of his recalcitrant shadow. Wendy helps Peter sew his shadow back on. Enchanted by him, she and her brothers accept Peter’s offer to fly away with him to Never Never Land. There they join the Lost Boys, all children who left their parents before they grew up, but must also battle Peter’s sworn enemy, the black-hearted Captain Hook, who is determined to kill Peter for feeding him to the crocodile and making him lose his hand. When Hook learns that Peter has feelings for Wendy, he determines to seduce her away from him.

J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, originally produced as a play in 1904 and later turned into a novel by Barrie in 1911, must surely be counted as one of the two or three top all-time classics of children’s literature. The enduring popularity of Peter Pan may not necessarily be its greatness as a play or book but simply the purity of the fantasy it contains – it is a wish fulfilment of lost childhoods, of banishing all adult responsibility and living in a perpetual state of play fuelled with the unbridled power of dreaming, even being able to fly. The fantasy has become so enduring that the term ‘Peter Pan’ has become one used generically to describe adults who still delight in child-like innocence – and has notably been applied to figures like Michael Jackson and Steven Spielberg.

The play is frequently seasonally revived, while there have been numerous films adaptations – ranging from the silent Peter Pan (1924) to the well-remembered if over-rated Disney animated version Peter Pan (1953) and Steven Spielberg’s live-action sequel Hook (1991). (See below for other versions). As I write this, we are on the cusp of the centenary of the J.M. Barrie play (2004) and in response it seems that screens are being inundated by a whole host of Peter Pan-related films – Disney had earlier released an animated sequel to their film Return to Never Land (2002), as well as spun Tinkerbell off in a series of animated direct-to-dvd films beginning with TinkerBell (2008); there is this live-action remake of the story; there was the fascinating but little-seen Neverland (2003), which gave Peter Pan a modernised interpretation with Peter a kid suffering from bipolar disorder; while there was also the heavily fictionalised J.M. Barrie biopic Finding Neverland (2004) with Johnny Depp and a BBC quasi-dramatised centenary documentary Happy Birthday, Peter Pan (2005). A few years later also saw Nick Willing’s science-fiction rationalised retelling Neverland (2011), the prequel Pan (2015) and the Disney live-action remake Peter Pan and Wendy (2023).

This version of Peter Pan comes from Australian director P.J. Hogan, best known for the international Aussie comedy hit Muriel’s Wedding (1994) and frothy mainstream romantic Chick Flick fare such as My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997) and Confessions of a Shopaholic (2009). (Hogan’s sole other genre work was Dark Shadows (2005), the unaired pilot for a remake of the classic Gothic soap opera). Peter Pan was shot and produced at the Warner’s Movieworld studio on Australia’s Gold Coast.

It is a very eccentric production – one of the producers listed on the credits is Egyptian-born Mohamed Al Fayed, the millionaire owner of Harrod’s in London. Mohamed of course dedicates the film to his late son Dodi Al-Fayed, the companion of another fairytale princess who it seems holds an unalloyed sense of purity and innocence in some people’s hearts – Princess Diana (who also incidentally lived in exactly the same location as the Darling household – London’s Kensington Gardens). In another interesting development, the producers of this version of Peter Pan kicked Disney out of a co-production deal – it appears that after initial negotiations, Disney began to squabble over having to give profits to the Great Ormond Street children’s hospital in London to whom J.M. Barrie deeded all rights to Peter Pan when he died, which perhaps says something about how increasingly mercenary the Disney corporation has become.

This version starts out beautifully. P.J. Hogan captures a perfect sense of the Victorian children’s fantasy, both in the amazingly fantasticized set designs for Victorian London – like something straight out of Mary Poppins (1964) – and the adult tone of narration that comes over the film. The scenes in the Darling household have been extended much more so than J.M. Barrie gave them in the book and play. The intent has been to give a more substantial series of contrasts to the fantasy scenes – one where the introduction of the starchy Aunt Millicent character acts as embodiment of adult responsibility, invoking Mr Darling to become a man of station and learn how to hold proper conversations and Wendy to learn to be a woman.

This section comes with a saddening sense of the encroaching death of the child-like imagination enforced by the mantle of adult responsibility – Olivia Williams has a lovely piece of dialogue about how Mr Darling has to keep putting his dreams away in a drawer. It is in these scenes that P.J. Hogan achieves something reminiscent of the Victorian children’s fantasy of A Little Princess (1995) – of a wondrous childhood magic tempered with an underlying sense of adult emotions waiting at the edge.

This works well up until the point that the film arrives at Never Never Land where it becomes a less well-balanced prospect. Never Never Land is expectedly a wondrous and hyper-realised realm filled with amazing jungles, waterfalls and fabulous dark castles wherever one looks. The production design and effects team have a field day in these scenes. However, Peter Pan also feels like a film that has been over-produced, as though CGI and effects have been piled on for the sake of it rather than toward achieving any particular purpose – the initial journey to Never Never Land comes with an entirely gratuitous journey up into orbit and through the (or at least a) Solar System that contains more planets buzzing about than it would ever be astronomically possible; Peter’s sword duels with Captain Hook now involve Peter flying and doing mid-air acrobatics as though he had just stepped out of The Matrix (1999) – even Captain Hook gets into the flying antics at the climax; while Peter Jackson’s WETA Workshop have been called on to provide not a mere crocodile but something that has been pumped up to the size of a small house.

For all the lavishness of attention paid towards the world that it takes place in, Peter Pan is only a film that sporadically flies. Oh it does so sufficiently enough to offer a more than adequate flight of fantasy. It is also apparent that P.J. Hogan and co-writer Michael Goldenberg seem less interested in making a fantasy adventure than they do in deconstructing Peter Pan. The film feels at times exactly like an amateurish modern exercise in taking a familiar story/character and determining to psychoanalyse and project adult emotions onto it. Hogan and Goldenberg play up the romantic attraction between Peter and Wendy that only bubbled beneath the surface in J.M. Barrie’s work and the previous film versions – this version is after all all about Peter coming to learn what a kiss is.

Indeed, Hogan and Goldenberg change the story in a way that now makes it into something about competing sexual jealousies – Captain Hook sees Peter and Wendy wooing in the forest and desires to allure her away from Peter; Hook seduces Wendy over to his side by tempting her with the opportunity to become a girl pirate; Peter gets jealous when Hook twists this against him. It is something that one feels muddies and gives an extra unnecessary level of complexity to the character motivations that in the original simply were – Hook was mean and evil and the nearest he had to motivation was desiring revenge over the fact that Peter had made him lose his hand to the crocodile; Peter was unalloyed childhood innocence embodied and Wendy was attracted to him because of that, nothing more.

Furthermore, P.J. Hogan also takes the step of having both Captain Hook and Mr Darling played by the same actor Jason Isaacs (this is in fact a casting holdover from the original play). However, with the injection of a nascent sexuality, this adds a decidedly Freudian subtext to the characterisation of Captain Hook, with Hook now seeming like a dark embodiment of all the lost dreams and enforced responsibilities towards taking up his social station that Mr Darling is advocated to take. It is unfortunately something that also, when Hook starts going on about kisses to the pre-adolescent Wendy, gives the story a less-than-entirely-pleasant whiff of incest and paedophilia. It was certainly enough for J.M. Barrie’s granddaughter to publicly castigate the film’s overt portrayal of such as a betrayal of the original story.

Jason Isaacs is a fine actor who is now only starting to come into the British leading man aboard status that he has seemed on the verge of inheriting over the last few years. Isaacs, fine actor as he is, is also miscast playing Captain Hook. Jason Isaacs is a quiet and mannered actor who is capable of portraying a sparkling charm; what he fails to do is project much in the way of larger-than-life threat that a black-and-white villain like Captain Hook embodies. On screen, this film’s Captain Hook comes across as far too sympathetic, even at times weak, and not enough in the way of plain out-and-out dastardly. Far better is Richard Briers who gives us a wry and likeable Smee.

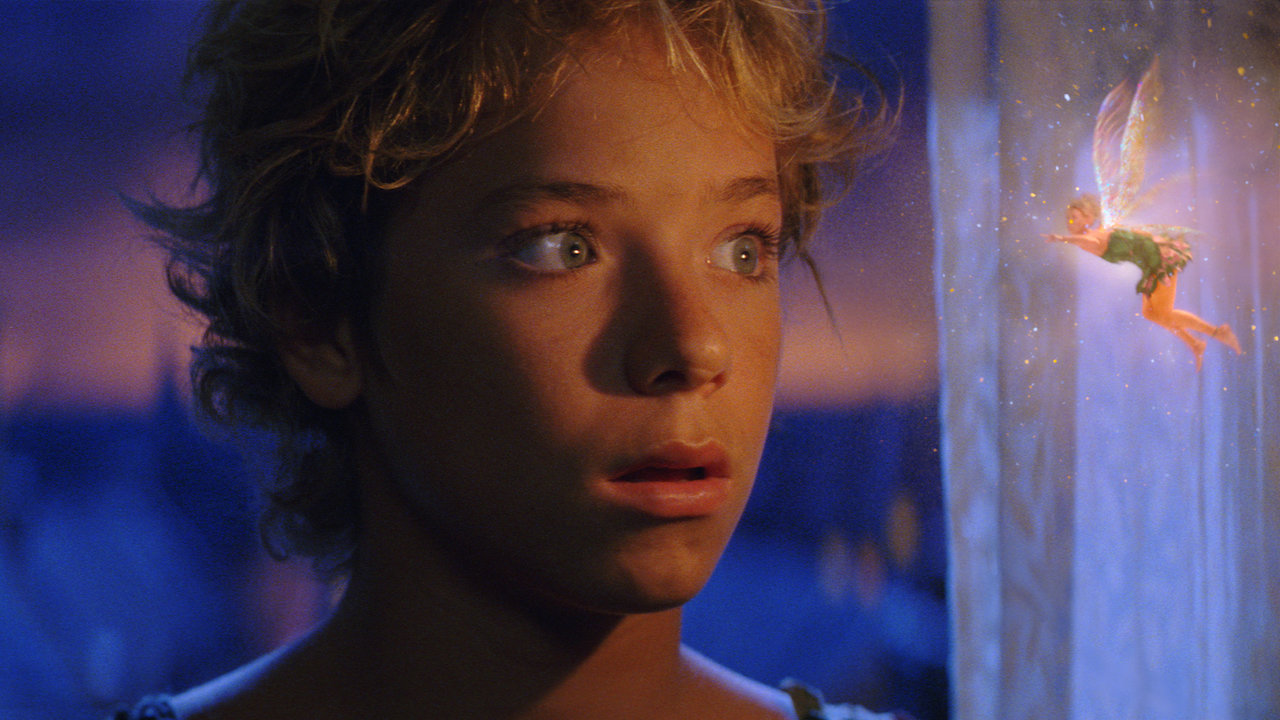

Jeremy Sumpter, snapped up after his amazing turn in Bill Paxton’s Frailty (2001), is also far too precocious a Peter. He is like a living embodiment of some toothpaste commercial where the character comes out shining like a battery of lights has been turned on inside them. Although the worst piece of casting is Ludivine Sagnier’s Tinkerbell. The characterization of Tinkerbell should have been fairly simple – something that came with a sparklingly ethereal innocence – whereas instead, for reasons entirely unknown, Hogan and Sagnier have chosen to play the character as some kind of ditzy airhead. On the other hand, Rachel Hurd-Wood has exactly the perfect degree of loveliness and sweetness as Wendy.

Other versions of Peter Pan are:– Peter Pan (1955), a live tv play; Peter Pan (1976), a tv movie version with Mia Farrow!!! playing Peter; and Peter Pan (tv movie, 2000). Steven Spielberg attempted to conduct a remake for many years and eventually mounted the live-action sequel Hook (1991), which concerns itself with a grownup Peter’s return to Never-Never Land. Disney made their own animated theatrical sequel Return to Never Land (2002), as well as a series of Tinkerbell dvd-released films with TinkerBell (2008), Tinker Bell and the Lost Treasure (2009), Tinker Bell and the Great Fairy Rescue (2010), Secret of the Wings (2012), The Pirate Fairy (2014) and Tinker Bell and the Legend of the Neverbeast (2014); and the live-action prequel Pan (2015). There was also the fascinating but little-seen Neverland (2003), which gave Peter Pan a modernised interpretation with Peter a kid suffering from bipolar disorder; the tv mini-series Neverland (2011), which offered a science-fictional rationalisation set on an alien planet; and the modernised Wendy (2020), which relocates the story in the Mississippi Delta. Finding Neverland (2004) was a biopic about J.M. Barrie and offered a heavily fictionalised account of the writing of Peter Pan.

Trailer here