Australia. 1975.

Crew

Director – Peter Weir, Screenplay – Cliff Green, Based on the Novel by Joan Lindsay, Producers – Hal & Jim McElroy, Photography – Russell Boyd, Pan Flute Music – Gheorghe Zamfir, Additional Music – Bruce Smeaton, Art Direction – David Copping. Production Company – The South Australian Film Corporation/The Australian Film Commission/McElroy and McElroy.

Cast

Rachel Roberts (Miss Appleyard), Dominic Guard (Michael FitzHubert), John Jarrett (Albert Cundall), Anne Lambert (Miranda), Christine Schuler (Edith), Margaret Nelson (Sarah Weybourne), Helen Morse (Mademoiselle de Poitiers), Vivien Gray (Greta McGraw), Karen Robson (Irma Leopold), Wyn Roberts (Sergeant Bumfer)

Plot

Valentine’s Day of 1900 in New South Wales, Australia. A classful of girls from the Appleyard girls boarding school go to nearby Hanging Rock for a picnic. Four girls ignore orders and sneak away to climb the Rock. Only one of the girls returns, screaming. The other three and a teacher, who was last seen in her underwear, have vanished. An extensive search of the area is conducted but no trace of the girls can be found. Parents withdraw their children from the school, causing its finances to plummet. The son of a wealthy British family, who saw one of the girls just before she vanished, becomes obsessed with finding her. He searches on his own and later finds one of the girls, who is found to have been sexually interfered with and her memory a blank.

This low ($450,000) budget effort started an international renaissance for Australian cinema. In a 1995 centenary of Australian cinema poll, The Picnic at Hanging Rock was voted No 1 of the Top 10 best-ever Australian films.

The Picnic at Hanging Rock is an incredible and haunting film. It is constructed as a puzzle. The film sets up a disappearance, dropping clues to mysterious happenings. Answers may or may not reside somewhere in the paranormal. There are hints of something unearthly – the mysterious red cloud, watches mysterious stopped at the same moment, the boy who later receives a vision of one of the girls. It could be UFOs, something supernatural or merely the mundane activities of a killer. The brilliance of the film is its arriving at an ending that frustratingly leaves the solution to the puzzle beyond the reach of its audience. It is a daring move. As a result, The Picnic at Hanging Rock is a film that resonates with a sense of enigma that continues to work the mind long after many of its individual details have faded in memory.

Director Peter Weir has clearly drawn upon films like Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), which set up a murder and an attempt to solve it, yet circled through various incongruous accounts of what happened while leaving the audience baffled as to the ultimate truth, and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966), an ostensible murder mystery that drew an audience into photographer David Hemmings’ realisation that he had captured evidence of a murder in a photo that ended with the photos stolen and the murder unresolved. Both of these are films that play upon the nature of the thriller and the whodunnit, forms that demand a resolution but where each film deliberately confounds by closing the door before any end resolution.

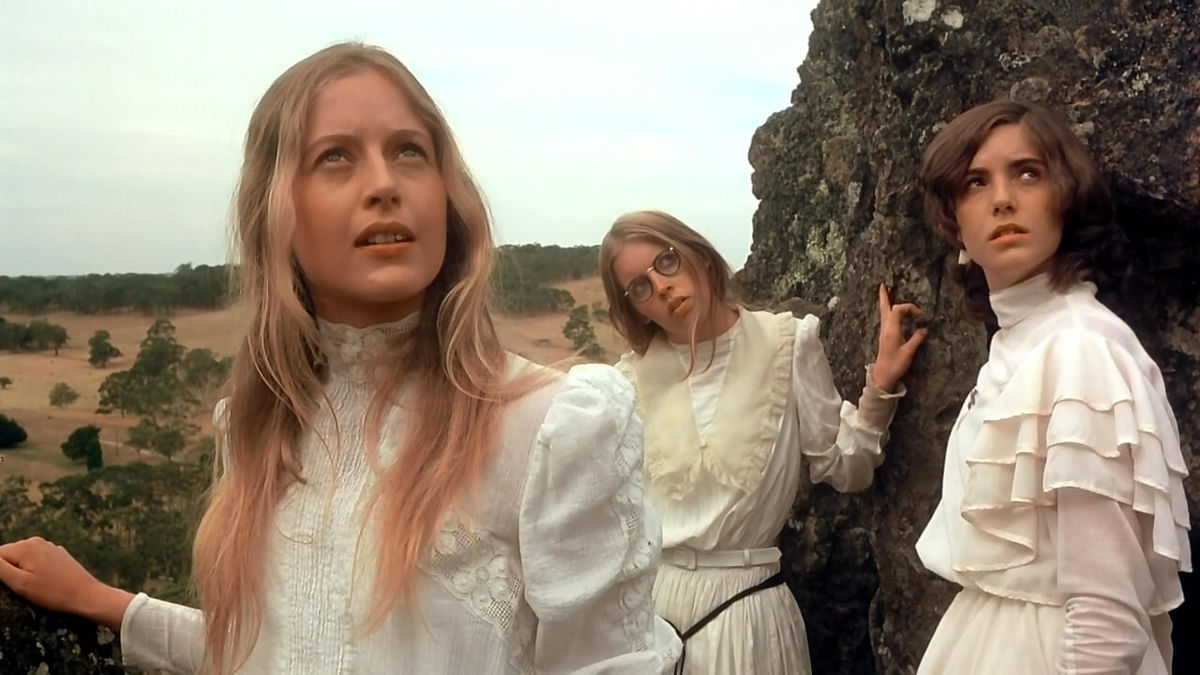

The Picnic at Hanging Rock is a beautifully photographed film. It takes place in a dreamy arthouse fantasy of girlish infatuation – of girls on picnics, reading poetry, professing naive love for one another. Peter Weir and photographer Russell Boyd fill the film with tableaux of the girls in white dresses, straw boaters and gloves, drifting in slow-motion sunlit dances through the arid landscape, accompanied by Gheorghe Zamfir’s haunting flute music. Over this hangs a disturbing sense of the immensity of time and the landscape itself exuding an almost physical presence. Hanging Rock itself sits in the film – not unlike the monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – like an opaque blank that defies any understanding. It is a film that seems to echo and resonate with a sense of the evanescent fragility of the social order up against the cruel vastness and indifference of geological time. Indeed, Australian cinema often resonates with this sense of the mythical primality of the desert landscape, of the land being something that operates on a different timescale to the human (the notion the Aborigines called ‘Dreamtime’).

Moreover, the film equates the land’s physicality with a sexual force. Over this dreamy sense of girlish infatuation, The Rock seems to hover like a looming shadow of sinister sexuality. Indeed, The Rock seems to literally exude a mysterious hypnotic power that intrudes into the initial dreamy romanticism – one of the most singularly disturbing images in the film comes to be their traversal of a defile in somnambulatory single file. As the girls draw toward the Rock, the primness of the social order seems to unravel – they shed their clothes. While it is not clear what happened, the two who return give the impression of having been raped.

You can even draw a number of similarities between The Picnic at Hanging Rock and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). In Dracula, the title character insinuates himself into Victorian upper-class society and then seduces its women, turning them into voluptuous, desirous figures. The story of Dracula contains an enormous Freudian charge – and clearly the forces of good, in staking Dracula, are asserting social repressions and banishing sexuality. The Rock here fulfils a not dissimilar function – its opaque mystery has a force that is sexual in nature and serves to tear apart the fabric of polite Victorian society. It does not take too much of a stretch of the imagination to substitute the Rock for a vampire and see it as exerting hypnotic thrall over the innocent girls and leaving them ravaged and drained of their blood. [The Picnic at Hanging Rock makes intriguing contrast to the girls boarding school vampire film Lust for a Vampire (1971)]. Although, unlike Dracula, the Rock is more rapist than seducer. The sense of the girls’ defilement is equally equated with the Rock’s having disrupted the social cohesion of the school’s order, where the disappearance is seen as having the effect of tearing down the social microcosm of the primly repressive Victorian school.

The combination of haunting unsolved mystery and broodingly sinister symbolism creates an atmosphere that is spellbinding. A resolution to The Picnic at Hanging Rock does however exist. The Picnic at Hanging Rock was not even originally intended as an ‘unsolved mystery’ until Joan Lindsay published her novel in 1967 and the publishers decided to withhold the final chapter that explained everything. That last chapter (which is only twelve pages long) was finally published as The Secret of Hanging Rock (1987). One will not spoil the explanation of what happens for people but to say that the explanation offered does conclusively push the mystery’s answer over into the fantastic.

One of the enduring myths that has grown up around The Picnic at Hanging Rock is that it is based on a true event. (This was an idea that began with Joan Lindsay herself who wrote a work of fiction but refused to ever say it was not true). The film makes the assiduous claims on the credits and in its promotion that what happened is true, although this is not the case, even though many people are prepared to fervently argue otherwise. Nobody has yet produced any newspaper clippings or documents that authenticate such a disappearance ever happened. Hanging Rock is a real place however – about 50 miles north of Melbourne – and the film’s popularity has considerably boosted its fame as a tourist destination.

Picnic at Hanging Rock (2018) was a tv mini-series remake in six one-hour episodes.

Peter Weir next went onto make the internationally acclaimed WWI film Gallipoli (1981). He has since gone onto make a number of strong and intelligent mainstream US films including The Year of Living Dangerously (1983), Witness (1985), The Mosquito Coast (1986), Dead Poet’s Society (1989), Green Card (1990), Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003) and The Way Back (2010). Peter Weir’s early work in his native Australia falls within the fantasy genre, including the bizarre The Cars That Ate Paris (1974) about a town that survives by luring people to car crashes; The Last Wave (1977) about an Aboriginal prophecy manifesting in the modern world; and The Plumber (1978), a strange culture clash comedy where a sinister handyman invades a woman’s apartment. Peter Weir’s sole subsequent work in the fantastic genre was the remarkable The Truman Show (1998) about a man who discovers that his entire life is being staged as a tv show.

Trailer here