Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer – Harry Hurwitz, Photography (colour + some scenes b&w) – Victor Petrashevic, Music – Igo Kantor & Irma E. Levin. Production Company – Maglan Films.

Cast

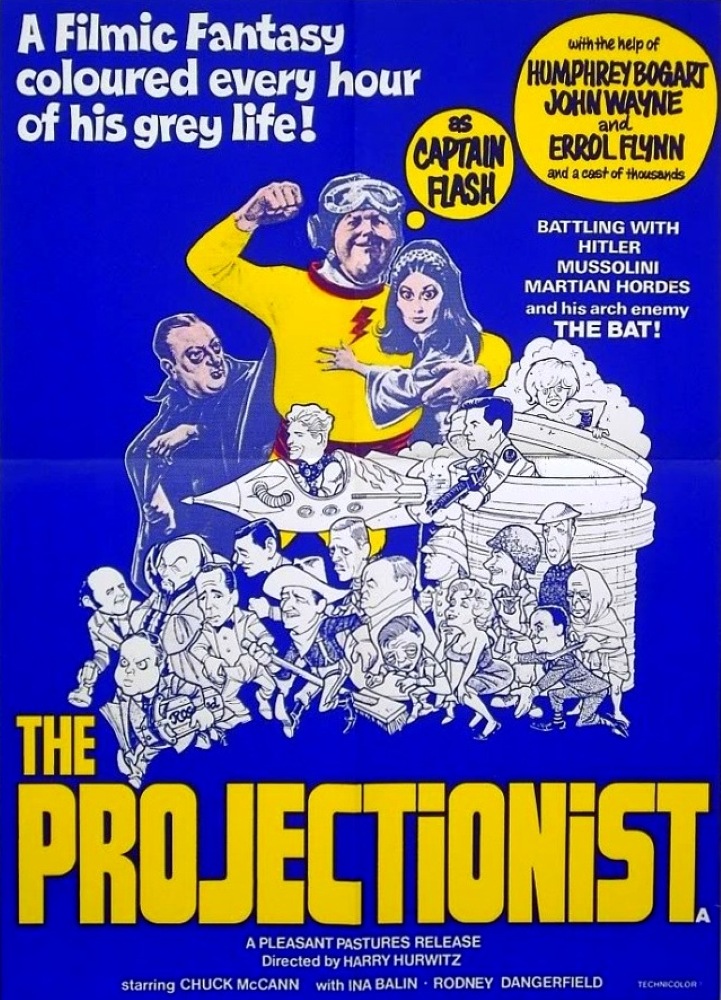

Chuck McCann (Chuck the Projectionist/Captain Flash), Rodney Dangerfield (Renaldi/The Bat), Ina Balin (The Girl), Jara Kohout (Candy Man/Scientist), Harry Hurwitz (Harry the Friendly Usher), Robert Staats (The Pitchman)

Plot

Chuck is a projectionist at a movie theatre in New York City. An avid movie fan, he is constantly daydreaming of movie scenarios where he is the superhero Captain Flash who is saving a girl and an aging scientist from the dastardly criminal The Bat who looks suspiciously like the theatre’s autocratic manager Renaldi.

The Projectionist is a film that you feel should have been a cult effort. It isn’t but most of the people who speak of it say things to a similar effect. Part of the problem is that the film has never had wide exposure. It disappeared shortly after it came out, seemed to slip by any kind of release during the video era and belatedly turned up on dvd in 2002.

You could call The Projectionist a version of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947) – wherein nobody Danny Kaye played out a fantasy life in daydreams – or maybe the much superior French-made Beauties of the Night (1952) – having been made for movie lovers. An actual remake of Walter Mitty has been announced since around the late 1990s, finally emerging with the disappointing Ben Stiller directed/starring The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013). Or perhaps even more so, a variant on the Buster Keaton classic Sherlock, Jr. (1924) wherein a milquetoast projectionist dreams himself into the story of the film.

Partially The Projectionist also falls into the trend for deflating superheroes that started around the late 1960s/early 70s after tv’s Batman (1966-8). Here much comedic emphasis is placed on the real-world awkwardness of the superhero – of seeing Captain Flash in baggy tights or his struggles to change into costume in a phone box.

Most of the scenes that take place in the movie fantasy consist of stock footage cannibalised from other films – throughout one was able to recognise clips from Charlie Chaplin’s His Prehistoric Past (1914), Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938), Citizen Kane (1941), Casablanca (1942), The Horn Blows at Midnight (1942), It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), Earth Vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), as well as various others from werewolf and mad scientist films. The film’s climax is a madcap escapade where Captain Flash’s battle against the villain (Rodney Dangerfield) is represented by a bewildering blur of clips that mix together Casablanca, Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars, Westerns and World War II combat films, even images of the Ku Klux Klan going into action. The wilful anachronisms and juxtapositions of eras make for some amusement. Director Harry Hurwitz’s triumph here though is managing to whip this madcap melange up into an exciting set-piece.

Even though it was not a great success, The Projectionist managed to be prophetic of a number of subsequent trends. Many films that followed took from ideas it laid down. It was one of the first films to prefigure the superhero with no powers comedy that we had several decades later with the likes of Special (2006), Defendor (2009), Griff the Invisible (2010), Kick-Ass (2010) and Super (2010), all of which make ironic contrast between comic-book superheroes and bittersweet reality. The Steve Martin film Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982) and various commercials and music videos during the 1980s took the idea of editing (and later digitally inserting) actors into classic film footage – here, for instance, it is made to seem that Chuck McCann visits Rick’s bar from Casablanca and mingles with the patrons.

The film was also prophetic of the whole cinema of Meta-Fiction that took off from the mid-1980s onwards – at one point, we see that the film Chuck McCann has been attending is the premiere of the film we are watching. In the last scene, Captain Flash and The Girl (Ina Balin) start dancing in the theatre and disappear into the movie screen together, where the scene then pulls back to show up on the movie screen in the theatre, while the projectionist version of McCann is left alone in his projection booth and turns the power off, whereupon the film ends.

Largely, The Projectionist is a film that is made with a love of silent routines – there is not much in the way of dialogue and the gags are very visual in nature. It is also a one idea film – lugubrious softie Chuck McCann is an average schmuck who has daydreams in which he ventures into a movie screen and plays out through various film genres. That is the sum of the film. There is no particular complication or development of the idea – even The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, while not a very good film, gives its idea some spin by adding romantic complications and a spy caper to the story. Chuck McCann does get a romance here but there is zero development or complication to it in the real world scenes – in a film like this, for instance, the romance in the daydream is usually an ironic contrast to the hero’s lack of success in the real world scenes.

The film has a mildly risque and occasionally out there edge to it. At one point, Chuck McCann visits an adult bookstore and start reading a pornographic magazine whereupon the girl inside the pages comes to life, which merges into a montage of whip-wielding dancers and nightclubs, interspersed with newsreel footage of Hitler. You could argue that this is prophetic of another cinematic trend and prefigures the Nazi erotic fascination that began with The Night Porter (1974).

There is also a satiric infomercial with a salesman (Robert Staats) pitching torture equipment for Christians. At another point, Hurwitz includes a montage that juxtaposes footage of John F. Kennedy and his famous “Ask not what your country can do for you …” speech with images of Hitler – although quite what he seems to be making a point about here, other than outrage for outrages sake, is something that escaped one.

Subsequently, Harry Hurwitz went onto a sporadic writing-directing career before his death in 1995. He made the satiric Richard (1972), a lampooning of the presidency of Richard Nixon; the documentary Auditions (1978) about actresses auditioning for a porn film; Fairy Tales (1978), an X-rated version of various fairytales; the disco vampire film Nocturna: Dracula’s Granddaughter (1979); the Hollywood spoof The Comeback Trail (1982); the comedy Safari 3000 (1982); the sex comedy The Rosebud Beach Hotel (1984); That’s Adequate (1989), a Hollywood mockumentary; and the erotic thriller Fleshtone (1994). He also wrote the screenplay for the disastrous flop of Under the Rainbow (1981), a comedy set behind the scenes of the making of The Wizard of Oz (1939).