Crew

Director/Story – Vincent Ward, Screenplay – Vincent Ward & Toa Fraser, Producers – Chris Auty & Don Reynolds, Photography – Alun Bollinger, Music – Karl Jenkins, Visual Effects Supervisor – George Port, Visual Effects – PRPVFX, Special Effects Supervisor – Paul Verrall, Production Design – Rick Kofoed. Production Company – Silverscreen Films/The Film Consortium/Endgame Entertainment/New Zealand Film Production Fund/New Zealand Film Commission/The UK Film Council/Capital Pictures/Wayward Film.

Cast

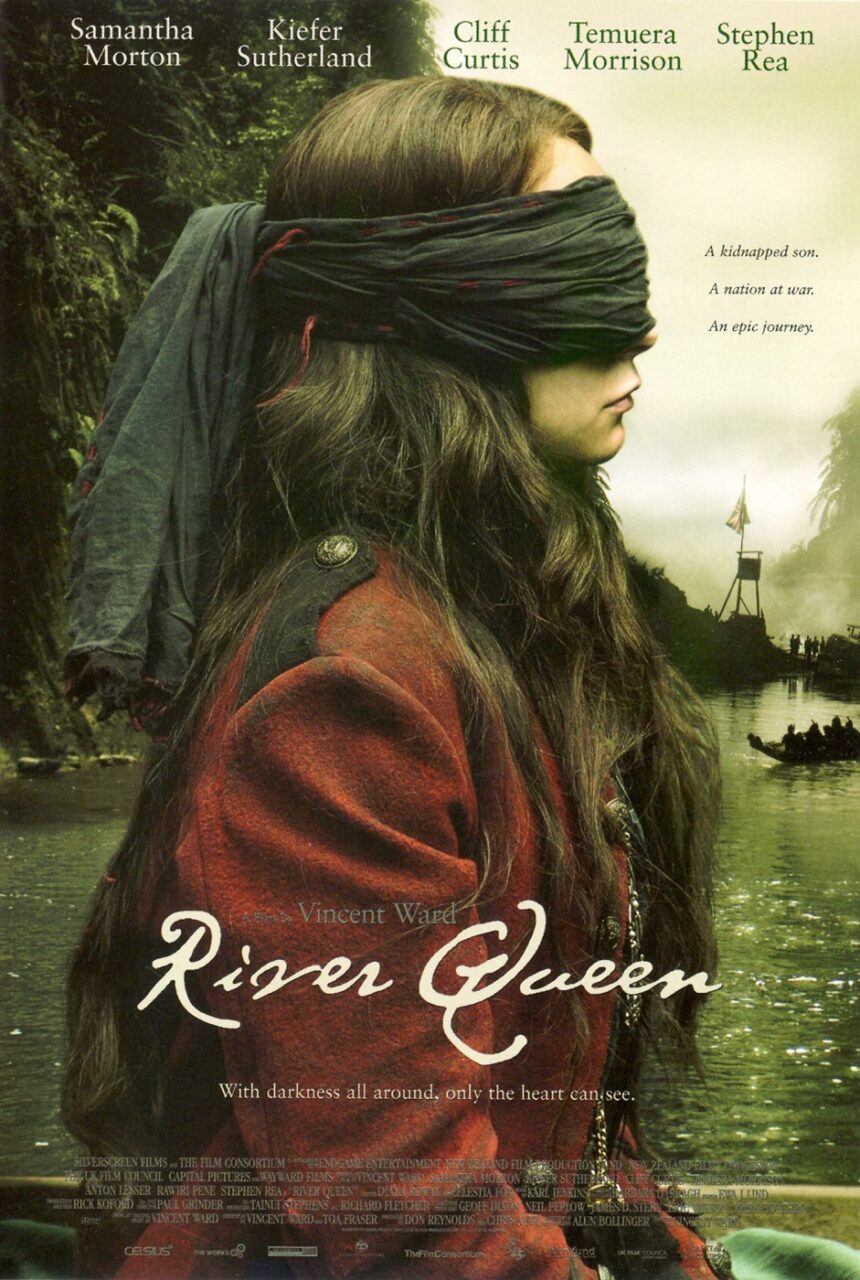

Samantha Morton (Sarah O’Brien), Cliff Curtis (Wiremu), Kiefer Sutherland (Corporal Doyle), Temuera Morrison (Te Kai Po), Rawiri Pene (Boy), Anton Lesser (Captain Baine), Mark Ruka (Hone), Stephen Rea (Francis O’Brien), Wi Kuki Kaa (Old Rangi)

Plot

Colonial New Zealand, 1868. Sarah O’Brien is an Irish settler who works as a medic. Sarah has given birth to a half-caste son from a Maori father whom she has named Boy and is raising him on her own after the father has died. Boy is then abducted by his Maori grandfather Old Rangi. The distraught Sarah spends the next seven years searching for Boy, trying to trace Old Rangi, the only moku artist in the area. She eventually finds Old Rangi, only to see him shot by British soldiers. Sarah is given protection by the British army. Wiremu, the brother of Sarah’s Maori lover who serves as a soldier with the British, then promises to take her to Boy if she will heal the tribe’s chief Te Kai Po. She is taken in secrecy into The Interior where whites are regarded with hostility by the Maori tribes. Sarah heals Te Kai Po and in doing so shares his dream of the conflict to come, only to then realise that she has saved the life of the man who is about to declare war on the British. She also meets Boy again – but he has grown up among the Maori ways and is hostile to the Europeans. As Sarah tries to find a way between both cultures, both she and Boy become essential figures in the coming war between the two sides.

I have maintained for a number of years now that New Zealander Vincent Ward is one of the great, underrated directors in the world. Even though most of his films get glowing reviews, Ward lacks much of a name outside of New Zealand and gets far too few opportunities to make films. After making two acclaimed short films, A State of Siege (1978) and the documentary In Spring One Plants Alone (1981), Ward first appeared with the feature-length Vigil (1985), which, if one can ever track down in international release, is a stunning work of cinematic art. Vigil is a film where Ward has sidestepped narrative and crafted the film as a single primal poem in light, shadow and muddy earth tones. Ward next made the time travel film The Navigator: A Mediaeval Odyssey (1988), which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and is about the meeting between Mediaevals and the modern day, which is seen in a series of frightening, primal images of terror. Ward next went to Hollywood and became caught up as part of the revolving door of creative talent involved with Alien3 (1992), before making Map of the Human Heart (1992), a somewhat remote Inuit love story, which was at least memorable for Ward’s stunningly surreal vision of the Wartime Blitz over London, as well as producing The Last Samurai (2003). Vincent Ward’s most financially successful film was the afterlife fantasy What Dreams May Come (1998), a remarkable work where he harnessed the emergent CGI technologies to create a vision of the afterlife as a world of classical paintings come to three-dimensional life. Ward co-writes River Queen with playwright Toa Fraser, later the director of No 2 (2006), the appealingly eccentric reincarnation drama Dean Spanley (2008), the Maori wars action film The Dead Lands (2014) and 6 Days (2017) about the Iranian Hostage Crisis.

River Queen was celebrated as the first film that Vincent Ward had made back in New Zealand in more than fifteen years. It was clearly mounted on the backs of the new renaissance of New Zealand cinema in the early 2000s – Peter Jackson’s mega-successful Lord of the Rings trilogy, Whale Rider (2002) – even though Vincent Ward had been there long before Peter Jackson or Niki Caro were ever known names. Alas, almost as soon as it began shooting, River Queen began to befall all manner of disasters. Indeed, if you were try to imagine a ‘making of’ documentary about River Queen, it might emerge as something akin to a sequel to Lost in La Mancha (2002). A group of radical Maori separatists announced in a local newspaper that they had placed a makutu (Maori curse) on the project, claiming the filmmakers had violated the river being used as location. Actor Cliff Curtis hit the headlines when he crashed through the living room of a house in his SUV while texting as he was driving.

The biggest problems with River Queen however appeared to be those that were going on on set. Lead actress Samantha Morton quickly gained a reputation as being someone who was difficult and highly demanding. Morton then fell ill with a dose of the flu, which caused the entire production to have to be shut down for five weeks. At this point, with River Queen spiralling over-budget, the completion guarantor (the insurer who determines the film is brought in on budget and time) was called in. In order to salvage the film, the decision was made to fire Vincent Ward and have the remaining scenes shot by cinematographer Alun Bollinger. A matter of weeks after shooting wrapped, the decision was made to rehire Ward and he receives sole directorial credit on the released film.

In films like this that come laden with all manner of pre-release stories about set disasters and conflicts between key personnel – see examples like The Island of Dr Moreau (1996), Titanic (1997) and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003) – the press usually alight on them with a gleeful feeding frenzy. One always ends up hoping – doubly so in the case of someone like Vincent Ward – that in all of it there is an artistic vision that someone was trying to persevere with that might still shine through despite everything. Alas, River Queen emerges disappointingly on screen.

It is not easy to pinpoint River Queen‘s problems. The plot feels like a distillation from two previous New Zealand films – Geoff Murphy’s epic Utu (1983) and its telling the story of the Maori Wars on a wide canvas from different sides of the conflict, and of Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993) about a determined woman in colonial era New Zealand and her tempestuous romantic quandaries. Although the film that River Queen reminds of more than anything else is John Boorman’s Amazonian rainforest drama The Emerald Forest (1985) about a man whose son is kidnapped by Indians, who spends years searching for him and eventually finds the son alive amidst a tribe who have never encountered civilisation before, where he realises that the son has been raised in the tribe’s ways, leaving him conflicted about which culture the son belongs to.

Ward also returns to the precognitive visions that fuelled The Navigator with both Samantha Morton and rebel chief Temuera Morrison experiencing a shared dream of events to come during the healing. The elements of the dream are brought together with a certain cleverness and ambiguity, although this precognition element is much less stronger here than it was in The Navigator and is only a minor plot element here.

River Queen‘s story feels sprawling. I never figured out what Kiefer Sutherland was meant to be doing in the story. (The sight of Kiefer running about in bare chest, kilt and beard, roaring with an Irish accent kept seeming faintly ridiculous, not to mention was constantly having its suspension of disbelief undercut by one unable to stop thinking: “It’s Jack Bauer in a kilt”). The story is on the constant move between the various parties and it often feels like Ward loses touch with the central narrative of Samantha Morton and the quest for her son. There is not nearly enough focus on her story.

Contrast River Queen with a very similar film, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), which has many parallels in its story about a man who ventures up a river into unknown territory to track down a rogue colonel. River Queen has a much stronger central drive to its story than Apocalypse Now – a mother venturing to find her missing son rather than merely a rogue military officer – but somehow Vincent Ward never gets in there emotionally with Samantha Morton’s journey. While Apocalypse Now‘s journey was lit up with a haunting and hallucinatory splendour, Vincent Ward only takes us along with Samantha Morton in occasional moments. To be fair to River Queen, the story does start to come together in about the last third and knits together nicely but the film that takes a long time to get there.

River Queen is also lacking in much of the visual poetry of the rest of Vincent Ward’s work. While Ward’s other films seemed fired up by extraordinary and haunting visions, River Queen seems at most a formula modern grittily realistic historical epic a la Braveheart (1955). Certainly, Alun Bollinger contributes some stunningly beautiful naturalistic photography of the Wanganui and Taranaki regions (in the middle of New Zealand’s North Island).

The film is not without some occasional moments of Ward-like poetry. I particularly liked the scene with Samantha Morton bound in the waka with her face palely illuminated amidst the gloom as she seeks to remove her blindfold and then a rifle barrel comes down and caresses her face to discourage her, before Ward pulls back to reveal that the holder of the rifle is merely a young boy (Rawiri Pene), as well as the later scenes where Morton tells the boy about her missing son before reaching out to caress his knee and finding the scar, realising that she has been talking to her son all along. The film is run over by an obtrusive and insistent pseudo-Celtic score. There are also some spotty digital effects – ships in bays and the like – from former Peter Jackson effects supervisor George Port.

Ward also shoots some tough and brutal war scenes, although these are probably the least satisfying aspect of River Queen. The film feels very much like it is making a concerted effort to be ‘historically realistic’ and is determined to be rough and muddy. However, the costumes and period dressings feel more like actors in dress-up rather than a window into an historic past. Indeed, when it comes to historic depth, it feels like River Queen never has much more to say than a Fifth Form New Zealand History essay that might get a C– mark – “English settlers treated the Maori badly, the Maori fought back bloodily, some Maori fought on both sides”. One was hoping that River Queen had something more substantial to say about its chosen subject than that. See however Vincent Ward’s subsequent film, the quasi-documentary Rain of the Children (2008) for a much more substantial journey inside Maori culture.

Trailer here