France/Belgium/Ireland. 2009.

Crew

Director/Story/Visual Development – Tomm Moore, Co-Director – Nora Twomey, Screenplay – Fabrice Ziokowski, Producers – Didier Brunner, Vivianne Vanfleteren & Paul Young, Music – Bruno Coulais, Animation Supervisor – Fabian Erlinghauser, Art Direction – Ross Stewart. Production Company – Les Armateurs/Vivi Film/Cartoon Saloon/France 2 Cinema/The Eurimages Fund of the Council of Europe/Media Plus Programme 121 Audiovisual/The Media Programme of the European Community/Canal+/Cinecinema/Conseil General de la Charente/Conseil Regional de Poitou Charentes/Piste Rouge/Bord Scannan na Heireann (Irish Film Board)/The Broadcasting Commission of Ireland/Flanders Audiovisual Fund/Centre du Cinema et de l’Audiovisual de la Communaute Francaise de Belgique/The Walloon Region – Prominage/The Walloon Region – Wallimage/Tax Shelter IngInvest of Tax Shelter Productions/Belgacom/Kinepolis Multi.

Voices

Ewan McGuire (Brendan), Brendan Gleeson (Abbott Cellach), Mick Lally (Brother Aidan), Christen Mooney (Aisling), Michael McGrath (Adult Brendan), Liam Hourrican (Brother Lung/Brother Leonardo), Paul Tylac (Brother Assoua), Paul Young (Brother Square)

Plot

The young orphan Brendan has been taken in at the monastery of Kells by his uncle the abbot. Brendan is greatly fascinated by the illuminated manuscripts the monks make and has become an apprentice. He becomes even more fascinated when Brother Aidan from the monastery of Iona seeks refuge at Kells to continue work on his legendary book, having been driven out by the Vikings. However, the abbot is more concerned with the coming Viking advance and erecting a wall to protect them than he is with Aidan’s work. Brendan befriends Aidan who starts to teach some of his secrets. Brendan agrees to undergo a venture into the forest, where his uncle has forbidden him to go, to obtain some of the berries Aidan needs to make ink. There Brendan meets and is befriended by the fairy Aisling. When he discovers what Brendan has done, the abbot responds by banishing him from working on the book and locking him away. Aisling steals the key so that Brendan can sneak into the forest and confront the fearsome god Crom Cruac in order to retrieve the crystal eye that is needed to make the most intricate hero page of the book. All of this is interrupted as the Viking hordes arrive and break through the monastery’s walls.

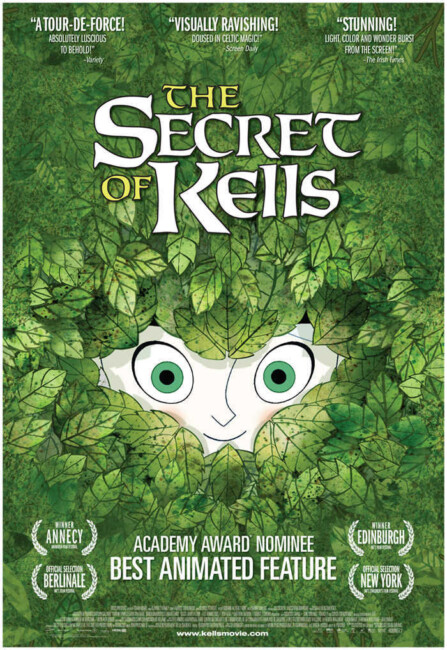

I must confess that I had never heard of The Secret of Kells prior to the announcement of the 2009 Academy Awards for Best Animated Feature. Now, the Academy Awards for Best Animated Film are no necessary indicator of great quality – look at other years when they have nominated inferior fare like Jimmy Neutron, Boy Genius (2001), Shark Tale (2004) and Shrek 2 (2004). On the other hand, their attention did serve to push Hayao Miyazanki from a cult festival figure to a breakthrough name with their award to Spirited Away (2001), while in recent years other works like The Triplets of Belleville (2003) and Persepolis (2007) have gained a big boost from attention in this category. The Secret of Kells was certainly a case of a film being a total unknown until such focus swung onto it, even though it was easily the left field entry in a race that was effortlessly swept up by Pixar’s Up (2009).

While most animated films are centred around talking animals or insufferably cute happenings, The Secret of Kells stands out by its very title alone. This is taken from The Book of Kells, which is the most famous of all illuminated manuscripts – it consists of the text of the four Gospels in Latin where the lettering and frame of the page has been elaborately illustrated and lettered. The exact date the Book of Kells was made is not known – it was created somewhere in the 9th Century by Celtic monks, it being so named after the Abbey of Kells in Ireland (not far from Dublin) where most of it was believed completed (after being started at the Abbey of Iona) and where it remained until the 16th Century.

Almost immediately, taking an historical subject and creating an authentic historically based setting, even casting the accents with authentic Irish voices, makes The Secret of Kells into a very different work than almost any other animated film out there. Few kids, for instance, are likely to pick up on namedrops of the various abbeys of the era or reference to Crom Cruach, a human sacrificial deity of pre-Christian Ireland. Disappointingly, the way the film has been made, it seems by its nature destined to be one that plays film festivals as opposed to being a multiplex hit.

Visually, the film is patterned after the illustrations in the Book of Kells. This lends to a unique form of stylised representation where characters are seen largely two-dimensionally, like something out of Michel Ocelot’s Kirikou and the Sorceress (1998), and have flattened out, blank features, not unakin to some demented artistic collision between Byzantine icon paintings and the characters in tv’s South Park (1997– ).

While the animation gives the appearance of being limited, what you have to commend the film for is its enormous degree of visual invention and the highly complex things happening within it. There are some exquisite watercolour landscapes and backgrounds. The frames are often designed like panels for illuminated manuscripts or break into split-screen panes. The backgrounds are frequently an amazing array of patterns and tessellations, like some kind of avant garde or psychedelic wallpaper taking over the frame.

One of the loveliest scenes is where Aisling and the cat contrive to steal back the key and free Brendan, a scene that passes through some beautifully drawn backdrops while accompanied by a haunting child’s voice singing on the soundtrack. The film reaches its artistic heights during the confrontation with Crom Cruac, which is designed as a patterned two-dimensional snake that moves at right angles and where Brendan manages to trap it by winding it into a self-enclosed square.

The story that supports the film is on the slim side, more often being there to support the visuals. The Book exists more to borrow the unique visuals from than necessarily tell a story about its creation – the journey into the forest for the berries and the crystal eye are mostly there to drive the plot. We are never given any explanation, for instance, as to why the abbot so obsessively and harshly wants to keep Brendan away from the outside world. The film does have a fair message about following the path of creativity and standing up against the voice of authority, control and safety often at personal cost and risk.

Director Tomm Moore next went onto make Song of the Sea (2014), another beautifully animated work set around Celtic mythology, the On Love segment of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet (2014) and then co-directed the full length WolfWalkers (2020).

Trailer here