Crew

Director – Mark Tarlov, Screenplay – Judith Roberts, Producers – Jon Amiel, Joe Caracciolo Jr & John Fielder, Photography – Robert Stevens, Music – Gil Goldstein, Music Supervisor – Christopher Brooks, Special Effects Supervisor – Connie Brink Jr, Crab Created & Operated by Paul Mantell, Production Design – William Barclay & John Kasarada. Production Company – Polar Entertainment.

Cast

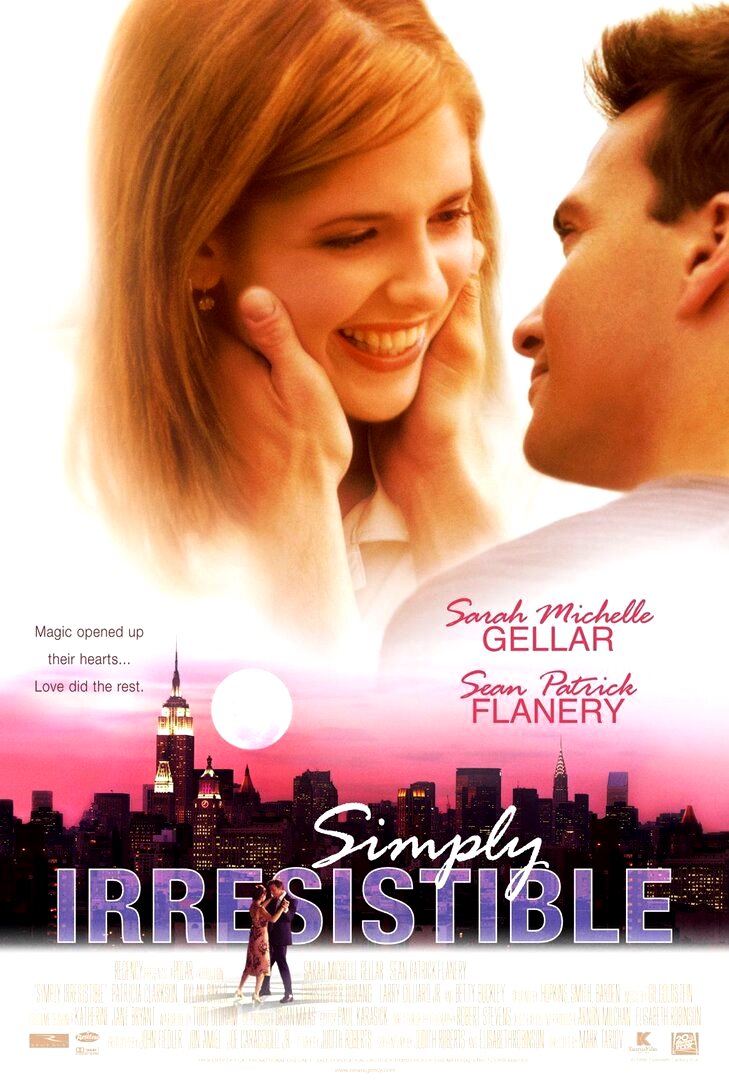

Sarah Michelle Gellar (Amanda Shelton), Sean Patrick Flanery (Tom Bartlett), Patricia Clarkson (Lois McNally), Larry Gilliard Jr (Nolan Traynor), Dylan Baker (Jonathan Bendel), Christopher Durang (Gene O’Reilly), Amanda Peet (Chris), Alex Draper (Francois DuMaier), Betty Buckley (Stella)

Plot

The restaurant that was left to Amanda Shelton by her mother is about to be sold. At the same time, Amanda suddenly gains magical cooking abilities, apparently granted by a crab that she carries home from the market. All the meals she now cooks have an incredible emotional effect on the people that eat them. These help her fall into the arms of Tom Bartlett, the executive in a new department store that is opening an upmarket restaurant. However, as Amanda is employed as the restaurant’s new chef, her magical abilities start to scare Tom away.

The term Magical Realism may well be more a creation of literary labelling and a desire upon the parts of some writers to seek a differentiation that separates them from standard generic fantasy – the same way horror films with pretensions try to insist they are not horror films – than it is any genuine subgenre. Whatever the case, Magical Realism has become associated with a certain type of fantastique storytelling – one that is related to an earthy (usually Latin American) tradition where the fantastic and the fabulist blend in as perfectly natural elements of storytelling. Most recently, Magical Realism has come to be associated with a certain type of romantic fantasy, one where fate, precognition, magical potions, angelic intervention and the like operate to influence the lives of lovers. It is a form of fiction that delights in wilfully improbable twists of contrivance that in any other genre would be regarded as melodramatically absurd.

There have been several efforts at Magical Realist films. The first of these was Robert Redford’s delightful The Milagro Beanfield War (1988), although that was arguably preceded by Bille August’s borderline entry Babettes Feast (1987), which was also about transcendental cooking. There have been a number of others – Simply Irresistible producer Jon Amiel’s Queen of Hearts (1989), The Butcher’s Wife (1991), Like Water for Chocolate (1992), Bille August’s disappointing adaptation of Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits (1993), Celestial Clockwork (1995), Rough Magic (1995), Chocolat (2000), Woman on Top (2000) and The Mistress of Spices (2005).

Simply Irresistible is an attempt to import Magical Realism into the formulaic genre of the romantic comedy. The plot, about a woman whose cooking weaves a magical spell that articulates the emotions she feels, is a straight steal from Like Water for Chocolate. Only where Like Water for Chocolate was a constant delight, Simply Irresistible fails to work in any way at all. The problem seems in part to be director Mark Tarlov’s failure to understand the genre. The whole point of Magical Realism is the very word Realism. Magical Realism works through its very unaffectedness, through its ability to make the fantastic and the everyday blend with a whimsical nonchalance.

However, the scenes of fantastic in Simply Irresistible seem constructed with haphazard regard. All that strikes about the film is the bizarre arbitrariness of the scenes. Scenes where food causes people to float up to the ceiling; a daydream where the two characters seem to momentarily enter a ballroom dance like something out of a 1950s Astaire/Rogers musical; a love scene where steam from a pot forms a layer of mist across the floor. The character of what seems to be the ghost of Sarah Michelle Gellar’s father turns up at the start of the film and later as a taxi driver who acts as deus ex machina to bring Gellar and male lead Sean Patrick Flanery together but the character is subsequently forgotten about without explanation as to what he was doing there or even who he was in the first place.

Other scenes make an impression only in their silliness – particularly one where Sarah Michelle Gellar’s cooking sends Amanda Peet into an uncontrollable fit, causing her to throw food and plates about in the restaurant, or the climactic scene where Gellar’s big dinner causes everybody to burst into uncontrollable tears. In Like Water for Chocolate, the scenes of each magical banquet were a capricious delight; by contrast in Simply Irresistible, they come so left field and so bizarrely awful that they only draw attention to the absurdity of the exercise.

Furthermore, Simply Irresistible fails to work as a romance either. What makes the romance (and indeed Magical Realism) work is dramatic tension. In Like Water for Chocolate, it was two lovers who have been cruelly separated, he forced to marry another woman and she forced to work as her mother’s maid; in The Butcher’s Wife, Celestial Clockwork and Rough Magic, it was improbable twists of plot contrivation that had lovers married to the wrong people, separated and even killed off before equally improbable twists of fate eventually brought them together in True Love; in The Milagro Beanfield War, it was angels stepping in to aid poor but honest Mexican farmers against ruthless landowners.

However, Simply Irresistible lacks any appreciable dramatic or romantic tensions. The two lovers realise their attraction early in the piece and the only tensions that subsequently develop are … well, he briefly pushes her away because he thinks she is a witch after they float up to the ceiling while kissing, and she is plagued with self-doubts (despite already knowing that she has the ability to create magically transforming meals) over whether she will make a big success of the restaurant’s opening night. The vagueness of these plot devices is infuriating. In any well constructed story, ex-girlfriend Amanda Peet would become the woman that Sean Patrick Flanery keeps getting drawn back to, possibly even engaged to, before fate intervenes to make him realise that he really loves Sarah Michelle Gellar; or else Dylan Baker’s boss would be a hard-ass who doubts Gellar’s abilities, something her triumph in the kitchen at the climax would finally silence by causing him to loosen up.

Not even the characters in the film work. Sarah Michelle Gellar, riding on the success of tv’s cult phenomenon Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2004), has inherited a role that in any other circumstances would be handed to Drew Barrymore. However, Gellar’s acting only ever seem to vary between a snooty cynicism, a self-reflexive awkwardness and a seeming series of audience asides – which may well be perfect for Buffy but does not make her a particularly endearing romantic lead here. She seems more like the whiny self-absorbed preppy girl you would be eager not to call again after the first date. Equally, Sean Patrick Flanery who, while he has proved himself a capable actor in the past – the likes of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1994-5) and Powder (1995) – seems no more than a handsomely tanned model in a designer suit whose concept of loosening up is to unbutton his shirt.

Director Mark Tarlov, better known as a producer notably for several John Waters film, has only directed one other film with the fantastical musical Temptation (2004).