USA. 1983.

Crew

Director – Jack Clayton, Screenplay – Ray Bradbury, Based on his Novel, Producer – Peter Vincent Douglas, Photography – Stephen H. Burum, Music – James Horner, Visual Effects Supervisor – Lee Dryer, Additional Visual Effects – Van Der Veer Photographic Effects & Visual Concepts Engineering, Photographic Effects – Peter Anderson, Art Cruickshank & Phil Meador, Mechanical Effects – Roland Tantin, Makeup – David Ayres & Robert Schiffer, Production Design – Richard MacDonald. Production Company – Walt Disney Productions/Bryna Co.

Cast

Vidal I. Peterson (Will Halloway), Jason Robards (Charles Halloway), Shawn Carson (Jim Nightshade), Jonathan Pryce (Mr Dark), Pam Grier (Dust Witch), Royal Dano (Tom Fury), Diane Ladd (Mrs Nightshade), Mary Grace Canfield (Miss Foley), James Stacy (Ed), Richard Davalos (Mr Crosetti), Jack Dengel (Mr Tetley), Bruce M. Fischer (Mr Cooger)

Plot

Dark’s Pandemonium Carnival arrives in Greentown, Illinois, and the townspeople willingly attend. 12 year-old Will Halloway and his best friend Jim Nightshade discover that the carnival people are creatures who live on the suffering of human beings. The carnival sideshows are designed to offer the townspeople the manifestation of their secret ambitions and desires so that in surrendering to them they lose their souls and are transformed into the circus’s freaks. When the carnival proprietor, the sinister Mr Dark, realizes that the boys know the truth, he comes after them.

Ray Bradbury was one of the handful of science-fiction and fantasy writers who was able to crossover into the mainstream and enjoy success there with works like Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1963) and short story collections such as Dark Carnival (1947), The Martian Chronicles (1950), The Illustrated Man (1951), The Golden Apples of the Sun (1953), The October Country (1955), Dandelion Wine (1957) and I Sing the Body Electric (1969).

The wistful poetry of Ray Bradbury’s writing has been called phenomenally difficult to translate to the screen – a notion that Bradbury himself ridiculed and that one tends to concur with. Certainly, there have been several prominent occasions where Bradbury’s whimsy and nostalgia has ended up being rendered with crashingly pedestrian literalism – the film version of The Illustrated Man (1969) and the tv mini-series adaptation of The Martian Chronicles (1980) being two notably guilty offenders. Equally, there have also been occasionally notable exceptions where Ray Bradbury has worked on screen – some of Francois Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966) and the tv anthology series The Ray Bradbury Theater (1986-92), where Bradbury successfully adapted many of his own short stories.

The crux of Ray Bradbury’s writing seems less about science-fiction and fantasy than it is about nostalgia and whimsy. Bradbury perpetually circles around and evokes a lost smalltown American childhood. When he was at his best, Bradbury seemed to encapsulate the sadness of a perfect smalltown childhood summer day that can never be recaptured. At its worst, Bradbury’s poetry was often heavy-handed – he seems like Walt Whitman overrun by Steven Spielberg on a bad day, or just an old-timer who has never kept up with changes whimsically embittered in their pining for a time when things were simpler or less complicated. Bradbury does have a propensity for poetic overkill – Something Wicked This Way Comes, both the script and novel, seems so densely laden in allegories and metaphors it is virtually impossible to decipher what Bradbury means sometimes.

Bradbury tried to push an adaptation of his novel Something Wicked This Way Comes (1963) for many years, trying to elicit people like Steven Spielberg and David Lean to the director’s chair. The adaptation finally reached audiences with Jack Clayton, who had made the classic ghost story The Innocents (1961), in the director’s chair and as a production backed by Disney. It was an occasion where Ray Bradbury obtained a fair treatment on the screen – primarily because he wrote the script himself.

Jack Clayton has a masterly affinity for the evocation of Ray Bradbury’s text. Clayton and cinematographer Russell Boyd (and one suspects with a helping hand from the special effects crew) create impossibly beautiful pastoral autumnal compositions – there is one gorgeous shot with fireside flames reflected off Vidal Peterson’s glasses – that would seem to live in no real world but the pages of Ray Bradbury-type lost childhood stories.

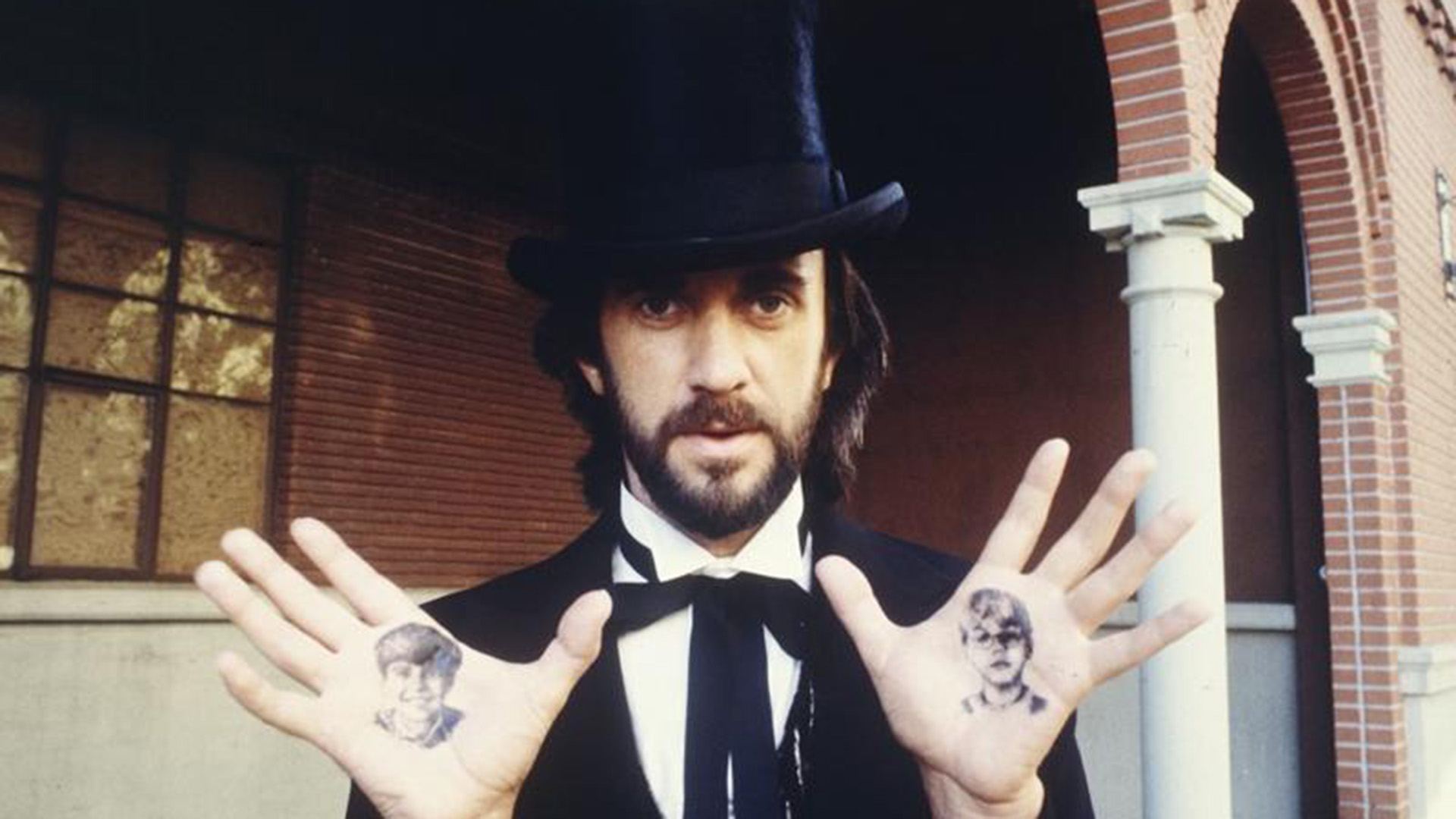

There are some superbly directed scenes. One of these is the parade through the town with the boys trying to hide from Mr Dark in a drain, which is a expertly connived piece of suspense – with Vidal I. Peterson and Shawn Carson nearly being given away by a barking dog as they hide in the drain; Jonathan Pryce’s Mr Dark taunting father Jason Robards to find their whereabouts, his hands painted with their pictures and blood from his clenched fists dripping unseen down onto the face of Peterson directly below Pryce’s feet; and the final poignant image of Peterson reaching up through the drain to touch hands with his father.

Jonathan Pryce makes a fascinating Mr Dark. Instead of playing with an elegant evil, Pryce gives the character a thuggish voice – rather than a coiled viper, he strikes out right and left in short, sharp bursts. The best scene in the film is one where Jonathan Pryce prowls through the library taunting Jason Robards about his oncoming age, tearing pages from a book that burst into flames as he tosses them over his shoulder. Here Ray Bradbury writes his very best dialogue for him, dialogue that breathes with a lingering poetry that can turn on the edge of an image:–

“We are the Autumn People. Your torments call us like dogs in the night. And we do feed, and feed well. To stuff ourselves on other people’s torments. And butter our plain bread with delicious pain … Funerals, marriages, lost loves, lonely beds – that is our diet. We suck that misery and find it sweet. We can smell the young ulcerating to be men a thousand miles off. And hear a middle-aged fool like yourself groaning with midnight despairs from halfway round the world.”

Something Wicked This Way Comes is an excellent film. James Horner delivers a superb score – the music that accompanies the arrival of the train in the town over the credits is a wonderfully shivery, eerie piece that runs right up and down the back of one’s spine.

Apparently Disney were not satisfied with the film that Jack Clayton turned in, deeming it too tame for contemporary audiences, and went and added some more visceral scenes – notably the spider attack on the house. In fact, this is the only part of the film that does not work. Who knows, perhaps the studio had a point though, in that Something Wicked This Way Comes was a financial flop for them.

Other Ray Bradbury screen works are:– the screenplays for the classic atomic monster movie The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and the classic alien body snatcher film It Came from Outer Space (1953); Francois Truffaut’s adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 (1966) about a dystopian future where books are forbidden; The Illustrated Man (1969), which adapts three Bradbury stories; the tv movie The Screaming Woman (1972) adapted from his story about a woman buried alive; the tv mini-series adaptation of The Martian Chronicles (1980); the tv movie The Electric Grandmother (1981) about an android granny; The Ray Bradbury Theater (1986-92), a tv anthology of Bradbury stories; his screenplay for the animated adaptation of the classic comic-strip Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989); the screenplay for the animated children’s film The Halloween Tree (1993); Stuart Gordon’s adaptation of The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit (1998) about a seemingly magical suit; A Sound of Thunder (2005) based on Bradbury’s classic time travel story; Chrysalis (2008) where a man mutates into another lifeform; and the tv movie remake of Fahrenheit 451 (2018).

Trailer here