USA. 1932.

Crew

Director – W.S. Van Dyke, Adaptation – Cyril Hume, Dialogue – Ivor Novello, Based on the Novel Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Photography (b&w) – Clyde De Vinna & Harold Rosson, Art Direction – Cedric Gibbons. Production Company – MGM.

Cast

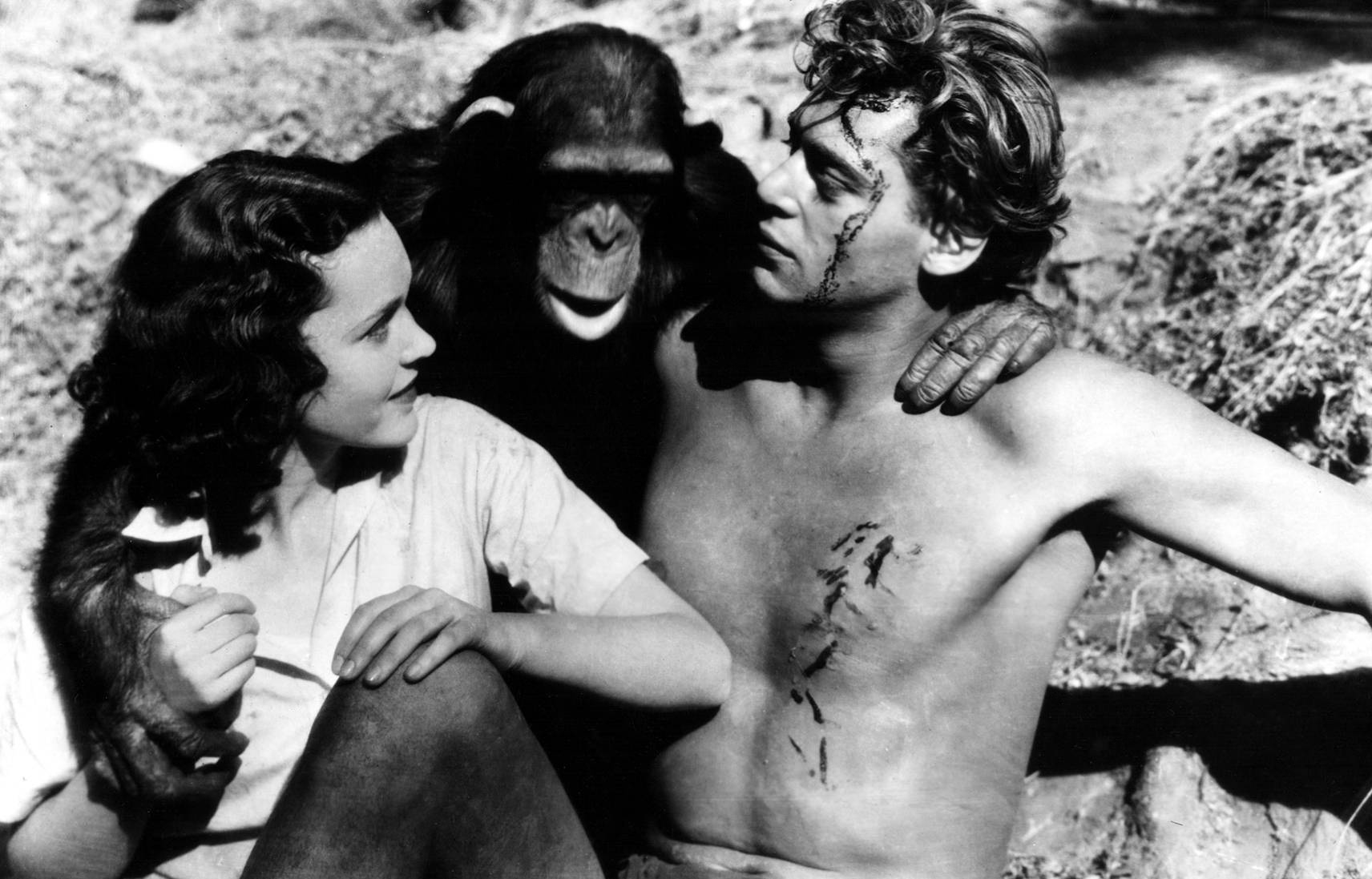

Johnny Weissmuller (Tarzan), Maureen O’Sullivan (Jane Parker), C. Aubrey Smith (James Parker), Neil Hamilton (Harry Holt)

Plot

Jane Parker arrives in Africa to visit her father who runs a trading store. When Jane learns that her father and Harry Holt are about to mount an expedition to the unexplored Mutia Escarpment, which they believe holds the location of the fabled elephant’s graveyard and a vast source of ivory, she insists on coming too. On The Escarpment, they are startled by the appearance of Tarzan, a white man in a loincloth who lives as an ape. Tarzan abducts Jane, taking her to his home among the trees. There Jane starts to fall for Tarzan and is torn between staying with him and returning to civilisation.

Tarzan was the creation of pulp writer Edgar Rice Burroughs. Tarzan first appeared in Burroughs’ second novel Tarzan of the Apes (1912) and he would go on to write a further twenty-one Tarzan books. This film is where the vastly more enduring Tarzan cinematic legend essentially began. Tarzan had been filmed before – including Tarzan of the Apes (1918), the silent version with Elmo Lincoln and five other films in the 1920s – but the character that everybody knows as the screen Tarzan today with all the “Me Tarzan, You Jane” jokes began with this film, a lineage that has resulted in innumerable films and tv series. 95% of all Tarzan films are not worth watching, however this, the first sound version, is one of the few that is. Its’ immediate sequel Tarzan and His Mate (1934) is the best of all Tarzan films, but Tarzan the Ape Man runs second place.

Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950) was a popular writer of adventure novels, who started publishing with A Princess of Mars (1912). Burroughs created many characters and series throughout his writing career, including John Carter of Mars, the Pellucidar and the Caprona series, although Tarzan is the character he will always be associated with. Tarzan is a white man’s fantasy of the Noble Savage. The Noble Savage was an idea that grew up in 17th and, in particular, 19th Century literature of how a man is truly himself when he is stripped of the trappings of civilisation – “nature’s gentleman.” It was a highly romanticised notion that many native tribes of this era were often portrayed as by Western writers. Tarzan is the ultimate embodiment of this – someone who is able to live freely in the jungle as one of the beasts, he literally becoming the king of the apes, yet operates according to a civilised code of decency and honour.

The silent 1918 Tarzan, which Edgar Rice Burroughs was involved with, was very faithful to the original book. However, from this point, there came to be a considerable divergence between what Burroughs conceived and the film portrayal of Tarzan. From the 1932 version here onwards, there would be no explanation of who Tarzan is. In the book, he is the son of John Clayton, Lord Greystoke, a British heir who is abandoned on the coast of Africa with his wife after a ship’s mutiny, where the parents are killed and the infant Tarzan is adopted into a tribe of apes by a mother whose own child has died.

In this film, Tarzan comes shorn of any connection to his baronial heritage and the Greystoke title. Gone too is an explanation of being found and raised by the apes. (Indeed, throughout the Johnny Weissmuller series and or any film that followed up until the 1980s, we never find how Tarzan ended up living in the jungle). The reason for this is possibly demonstrated by the 1918 version, which follows the novel closely but showed it was difficult to convincingly portray apes as characters while relying only on trained animals or unconvincing monkey suits. It was not up until the sophisticated animatronic ape suits in Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984) or else the talking apes in the Disney animated Tarzan (1999) that cinema started to feel comfortable with portraying this side of the Tarzan story.

The film also has Tarzan learning to speak English from Jane, although this is only pidgin English, something that became forever associated with the character, whereas Edgar Rice Burroughs had Tarzan learn to speak and write proper English. Burroughs also located Tarzan’s homeground on the coast of Africa; however, all the films in the MGM/RKO series invent the entirely new territory of The Mutia Escarpment – an untrodden plateau that lies in unexplored territory inland (something that became forgotten about in the subsequent films that had the area visited by an inordinate number of explorers and native tribes and was often within a stone’s throw of a trading post).

The film’s story starts with introduction of Jane – she becomes the point-of-view character instead of Tarzan and the film follows her journey through Africa to meet Tarzan, whereas in the book she only enters halfway through and the early section deals with Tarzan’s childhood. (She has also now been renamed Jane Parker instead of Porter, for some reason). Unlike Edgar Rice Burroughs, the film plays the story less as an adventure and more as an oddball romance. There is a charming innocence and dreamy romanticism to the scenes of the two of them playing in the treehut and frolicking in the water without being able to verbally communicate. The film does approximate some of the scenes that Burroughs describes in the book with Tarzan snatching Jane away, wrestling a lion to protect her and sleeping outside the treehut to guard her.

Unlike the end of the book, which has Jane return to Baltimore and Tarzan follow and propose to her, the film ends with her deciding to settle down in Africa with him. This becomes crucial to the sequels, which have the two of them living in domestic harmony in a treehut, waited on by Cheeta and an elephant that winches an elevator up and down. They even find a son – who falls from the sky in Tarzan Finds a Son (1939) because the Hays Code of the 1930s demanded that an unmarried couple could not give birth to a child.

Tarzan the Ape Man 1932 was made before the rest of the Johnny Weissmuller films turned the Tarzan and Jane relationship into a cosy jungle parody of middle-class life, before the addition of youthful sidekicks and scene-stealing comic-relief animals and an endless series of big game hunter/evil villagers plots dragged the series down into the most routine of formulas.

This version comes with a freshness that even its reduction to stock footage in later entries has not eclipsed. The animal action scenes are genuinely exciting – attack by water buffaloes as the explorers cross a lake on raft, with native bearers being tossed into the lake and (in one amazingly graphic piece of off-screen suggestion) being devoured by crocodiles; fabulous scenes of Tarzan conducting acrobatics and swinging through the trees in vast 40 foot loops; he wrestling leopards and gazelles hand to hand; an amazing sequence where, while wounded, he is forced to fight two lions before an elephant rescues him, carrying away his unconscious body with one arm wrapped around its trunk and dousing him with water by the river; the fabulous climax where pygmies capture the party, lower the bearers down into the pit to have their heads bitten off by the killer ape, where Tarzan comes to the rescue and stabs the ape in a ferocious fight, before the village is invaded by a horde of elephants, smashing up and trampling the huts and natives.

Tarzan was played by former five times Olympic gold medal winning swimming champion Johnny Weissmuller. Weissmuller acts like a churlish chimpanzee and is amusingly paired with the wonderfully bubbly and excitable Maureen O’Brien, who became the screen’s quintessential Jane. Watching the two of them play in the treehut is fun and the scenes with them frolicking in the water, playing without being able to verbally communicate, are quite sweet.

The film has many crudities as a result of the time it was made – it was 1932, only five years after the advent of sound film, so the film lacks a musical score, which it seems to cry out for during the action scenes. There are long fades between scenes and few closeups. None of the Johnny Weissmuller films ever visited Africa. All were shot on Hollywood backlots – the furthest they ever travelled was Acapulco in Tarzan and the Mermaids (1948). One can see the painted backdrops that make up many of the junglescapes, while we get scenes filled with stock footage of animals and native tribes where the actors have clearly been placed in front of a back projection screen.

Undeniably, condescending racial attitudes show through. Tarzan (both in Edgar Rice Burroughs and the Johnny Weissmuller films) represents very much a white colonial vision of Africa – of how a white man discovers his true self and finds his superiority to the native tribes, who are regarded as superstitious and ignorant. None of the native actors (all played by African Americans) are with the exception of Ivory Williams given credits listing in the film, for instance. Jane makes silly little comments about tribal headdress “oh look, every man his own feather duster.” At one point, Parker himself says “These people living like that have no emotions. Hardly human.”

Tarzan has become one of the most prolific screen characters of all time, producing some 80 films and five different tv series. Other direct adaptations of the Edgar Rice Burroughs novel include Tarzan of the Apes (1918), the silent Elmo Lincoln version; Tarzan the Ape Man (1959) starring Denny Miller; Tarzan the Ape Man (1981), a softcore version featuring Bo Derek and with Miles O’Keeffe as Tarzan, which is a direct remake of this film; Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984), a lavish version starring Christopher Lambert that returns to the original novel; Tarzan (1999), the Disney animated version; and the motion-captured animated Tarzan (2013) starring Kellan Lutz.

The other Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films are:– Tarzan and His Mate (1934), Tarzan Escapes (1936), Tarzan Finds a Son (1939), Tarzan’s Secret Treasure (1941), Tarzan’s New York Adventure (1942), Tarzan Triumphs (1943), Tarzan’s Desert Mystery (1943), Tarzan and the Amazons (1945), Tarzan and the Leopard Woman (1946), Tarzan and the Huntress (1947) and Tarzan and the Mermaids (1948). Maureen O’Sullivan (later the mother of Mia Farrow) appeared as Jane in the first six films.

Trailer here