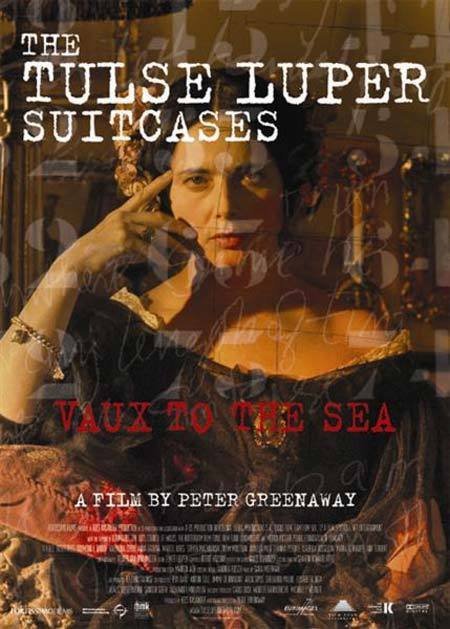

Spain/UK/Luxembourg/Hungary/Italy/Germany/Russia. 2004.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Peter Greenaway, Producers – Kees Kasander, Photography – Reiner van Brummelen, Music – Eduardio Polonio, Production Design – Pirra. Production Company – BS Production s.l./Via Digital/Televisio de Catalunya/Kasander Productions Ltd/Delux Productions/Focus Film/Gam Film/Net Entertainment/12 A Film Studios/The Art Council of Wales/The Rotterdam Film Fund.

Cast

J.J. Feild (Tulse Luper), Roger Rees (Tulse Luper), Isabella Rossellini (Madame Moitessier), Steve Mackintosh (Gunter Zeloty), Ana Torrent (Charlotte des Arbes), Nur Al Levi (Cissie Colpits), Raymond J. Barry (Stephen Figura), Marcel Iures (Genera; Foestling), Ana Maria Galiena (Madame Plens), Franka Potente (Trixie Boudain), Ornella Muti (Matilde Figura), Annabelle Apsion (Mrs Haps Mills), Scott Handy (Wolfgang Speckler)

Plot

In 1939, Tulse Luper is held a prisoner in Vaux Chateau in France by occupying Nazi troops. Escaping, he makes his way to Strasbourg where he becomes the manager of a cinema. Fleeing from there, he takes shelter in the home of Monsieur and Madame Moitessier who like to keep refugees under their roof.

Director Peter Greenaway emerged during the 1970s with a series of experimental films. He caught public attention and became an arthouse favourite during the 1980s through to the mid-90s with films such as The Draughtsman’s Contract (1981), The Belly of an Architect (1987), Drowning by Numbers (1988), the hit of The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989), Prospero’s Books (1991), The Baby of Mâcon (1993) and The Pillow Book (1996).

Later Greenaway films – the likes of 8½ Women (1999), the Tulse Luper films, Nightwatching (2007) and Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2015), as well as various documentary work – have not held the same interest for audiences that they used to, where he was seen variously accused of retracing old ground and not holding the sharpness he once did. Indeed, everything from The Tulse Luper Suitcases onwards has played to increasingly smaller audiences. The complaint that seems evident to me is that Greenaway seems to have increasingly abandoned narrative film in favour of the screen as a form of hypertext-come-cinematic art installation.

The Tulse Luper Suitcases was part of a massively ambitious undertaking on Greenaway’s part. This included three films – The Tulse Luper Suitcases 1: The Moab Story (2003), The Tulse Luper Suitcases, Part 2: From Vaux to the Sea here and The Tulse Luper Suitcases Part 3: From Sark to the Finish (2004), as well as an edited down version of the saga A Life in Suitcases (2005), two books, a website and an internet game The Tulse Luper Journey. Greenaway also wanted to release a tv series and a total of 92 dvds, cd-roms and books (92, being the atomic number of uranium, has a repeated significance throughout Greenaway works), although some of these others did not emerge.

I saw The Moab Story at a festival screening but it received a very middling reception even from Greenaway fans. From Vaux to the Sea and From Sark to the Finish played some festivals but found even less of an audience. The main part of the problem is that Greenaway intended The Tulse Luper Suitcases as part of a massive multimedia installation and the full effect of this is not evident watching them as individual films.

The other problem that becomes evident watching From Vaux to the Sea on its own is that while The Moab Story held interest somewhat and gave the impression that successive instalments might be going somewhere, this does not. What started out seeming like the opening chapters of a story has merely become a series of static scenes that give little impression they hold any dramatic momentum. This is not helped by Greenaway shooting many of the scenes in master shots that frame the entire set as a stage as though the audience is watching a play. This is broken by the constant hyperactive intrusion of pop-up frames, text running across the screen or notes about significant characters and objects. It is visually busy and occasionally interesting but it serves more as a distraction than anything else.

Rather than any kind of plot, it becomes apparent that Greenaway is making a film that is not so much a dramatic work than it is another of the long series of nonsense lists that run throughout his work – most notably the lists of rules for imaginary games that appear in Drowning By Numbers. More than anything, The Tulse Luper Suitcases feels like a more elaborate extension of the game that Greenaway played in The Falls (1980) – of creating a series of vignettes of nonsense stories about made-up characters and situations.

You can appreciate the film for the visuals, the art direction and the costuming, applaud Greenaway for the formality of his dialogue and some of the arcane references and even puns he throws in. Not to mention the constant self-referentiality of his films – various of Luper’s plays and operas are said to have formed the basis for The Draughtsman’s Contract and The Baby of Macon, while other Greenaway films are referred in the other chapters.

There is the odd moment of appealingly outright surrealism – a scene where Isabella Rosselini performs a ritual where she calls out names of people in her life and smashes ceramic dogs with a riding crop while one servant bangs random keys on a piano and another barks like a dog. But does it make for an interesting film? Not really.

Peter Greenaway’s other films of genre interest are:– the surreal post-holocaust ‘documentary’ The Falls (1980); The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989); several episodes of the modernised tv series A TV Dante (1989-91); Prospero’s Books (1991), Greenaway’s interpretation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611); and the miraculous child film The Baby of Mâcon (1993). The Greenaway Alphabet (2017) is a documentary about Greenaway.

Full film available here