Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer – Martin Rosen, Based on the Novel Watership Down (1972) by Richard Adams, Music – Angela Morley, Music Director – Marcus Dods, Animation Director – Tony Gay, Animation Supervisor – Philip Duncan. Production Company – Neptune Productions.

Voices

John Hurt (Hazel), Richard Briers (Fiver), Michael Graham-Cox (Bigwig), Zero Mostel (Kehaar), Harry Andrews (General Woundwort), Hannah Gordon (Hyzenthlay), Denham Elliott (Cowslip), Ralph Richardson (Chief Rabbit), Roy Kinnear (Pipkin), Michael Hordern (Frith)

Plot

The rabbit Fiver has a vision of a field of blood and is certain that something terrible is about to happen and that the warren must move. However, the Chief Rabbit dismisses Fiver and his brother Hazel when they approach him with this. And so Fiver, Hazel and a group of other rabbits make their own plans and leave. Their journey is beset by natural predators and traps. In setting up a new warren, they realise that they need to find does otherwise the warren dies with them. When then they hear of the dictatorship of Efrafa under the rabbit general Woundwort, they come up with a plan to infiltrate the general’s army and liberate the does there.

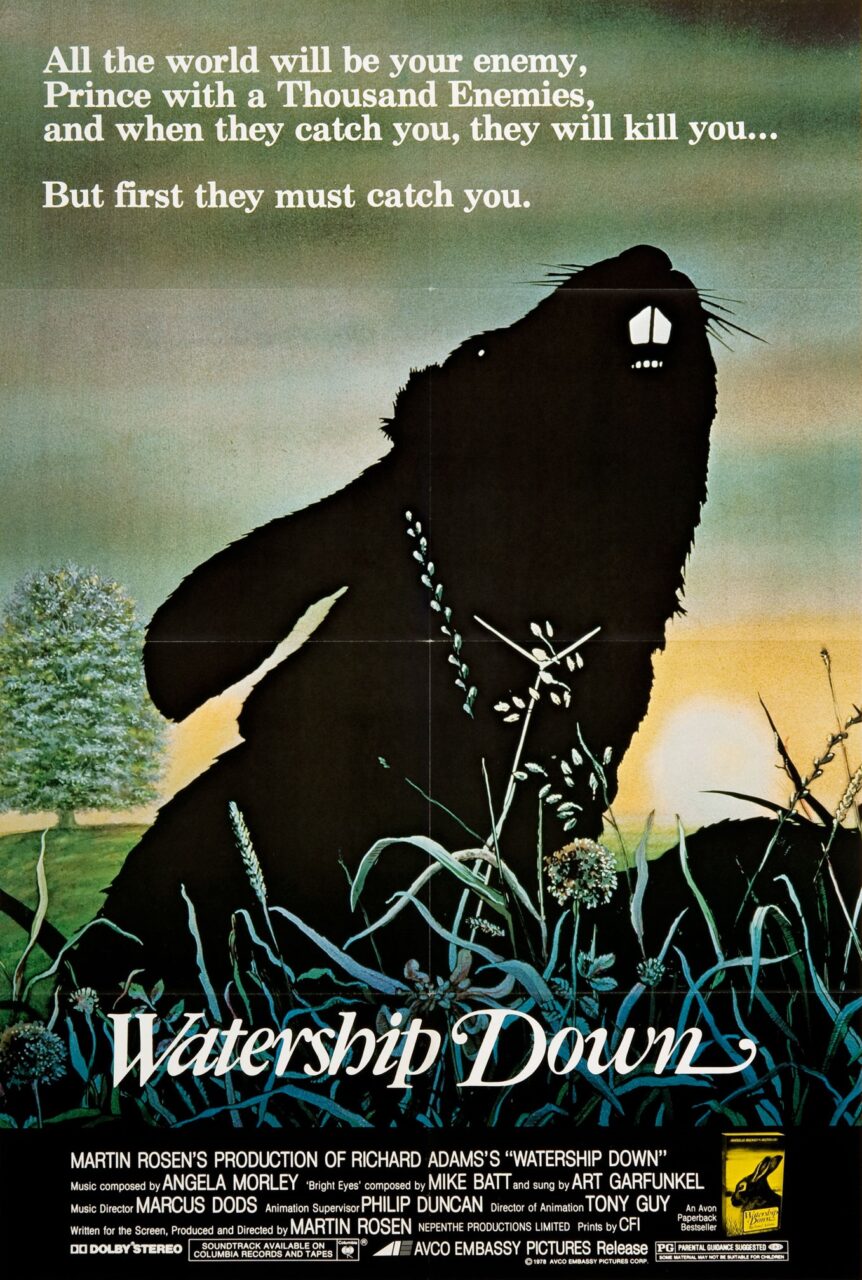

Upon its publication, Richard Adams’s Watership Down (1972) was one of those rare books that found equal appeal among adults as it did children. A BBC survey in 2003 named Watership Down as no 47 on the 100 greatest books of all time. This animated film adaptation was equally celebrated upon its release.

Watership Down is an extraordinarily good film. It is beautifully animated – the characters have a clear and rounded simplicity, the backgrounds come in watercolours that lovingly recreate the rural English countryside. The voice talents are chosen from the cream of the British acting community – names like John Hurt, Ralph Richardson, Harry Andrews, Michael Hordern, Denholm Elliott and Joss Ackland. (Of these, the most endearing is Zero Mostel’s turn as the wounded gull whose proud squawks are a comic delight).

Where Watership Down works is in its extraordinary evocations of the world as rabbits might see it in mythic terms. The opening sequence shows how rabbits might perceive creation myths, taking us through the formation of all rabbits as equal by the god Frith and then the origin of predators as punishment for the playfulness of the Trickster prince El-ahrairah, and the origin of the fluffy tail. It is an extraordinary piece of mythopoeia. And throughout, Watership Down is filled with equally extraordinary pieces of mythic imagery – like how the appearance of a train that providentially crushes pursuing rabbits is seen as one of the mysterious messengers of Frith.

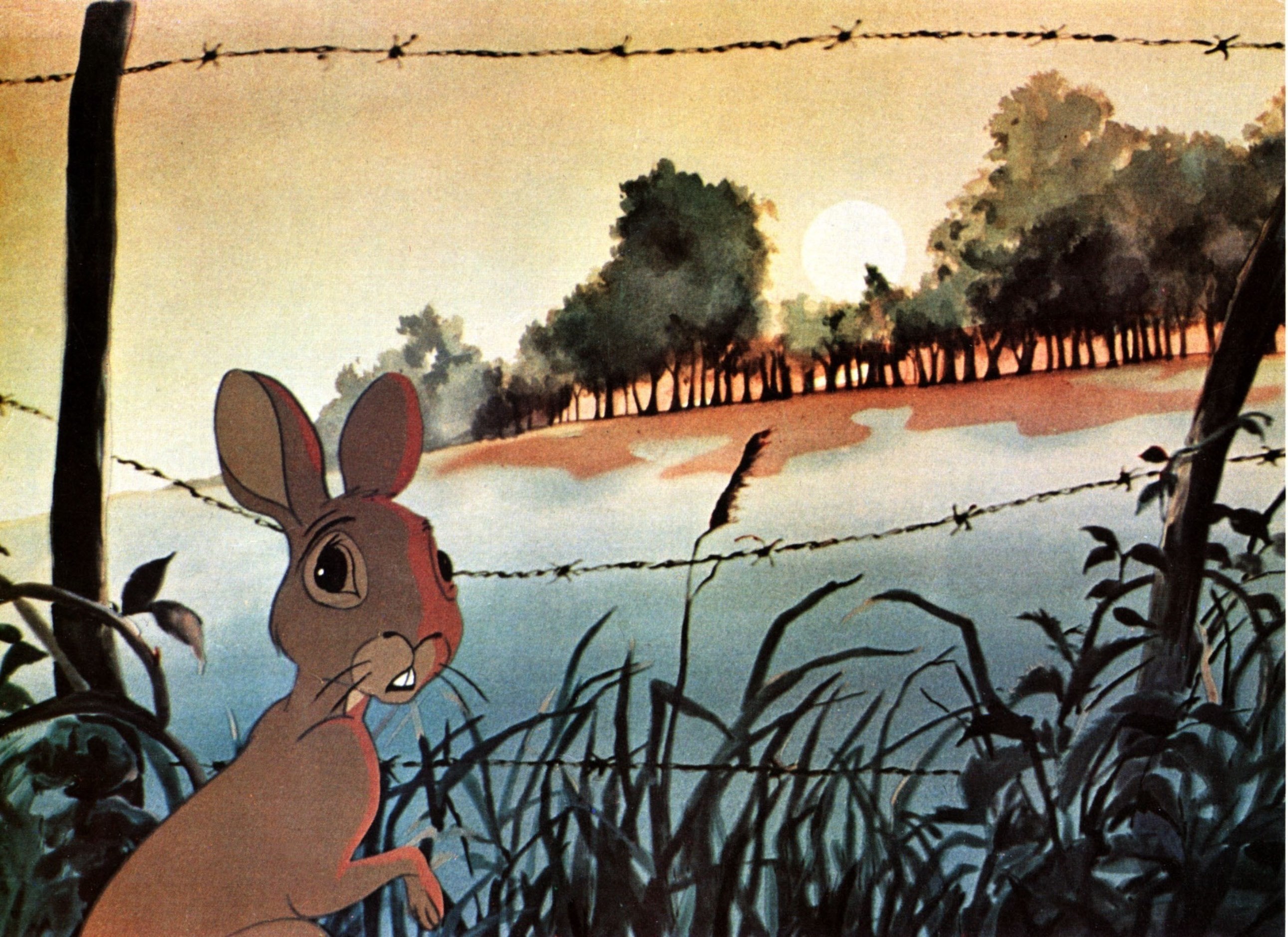

Like all classic fantasy, Richard Adams understood the emotional power of setting a small young person or persons of pure heart against the rest of the world. There is a heart-breaking frailty to some of the journey. The film works as much for its translation of Richard Adams’s book to the screen as for its willingness to deal with emotions that are rarely seen in Disney films – one of the most overriding images in the film is that of ever-present death. Unlike Disney, Watership Down is not afraid to show death as a real thing – the scene where Bigwig is caught in a trap and believed killed has a considerable brutality for a kiddie film and the narrated flashback describing the destruction of the burrow, telling of how the rabbits were forced together and crushed, is a extraordinarily dark piece as well. The venture into the poisoned burrow manifests an incredibly oppressive atmosphere.

The most heart-wrenching scenes in Watership Down are the appearances of the Black Rabbit of Death. The scene with Fiver following it over the hill when he believes Hazel has been killed, accompanied only by Art Garfunkel’s song Bright Eyes, is a moment that leaves an entire audience’s breaths’ frozen. The final scene with the appearance of the Black Rabbit to Hazel, gently asking him “Would you like to be in my Owsla? I know you would,” and Hazel lying down to die while his spirit capers off with the Black Rabbit is an ending so tragically sad that it guaranteed to leave every eye in the house, child and adult alike, going out wet.

Richard Adams went on to write a number of other animal stories, although none that have enjoyed the success of Watership Down. Watership Down director Martin Rosen later returned to make a film out of Adams’ The Plague Dogs (1982), about the adventures of two dogs escaped from a bio-research lab, although this was little seen bu is an excellent film well worth of rediscovery. The only other Richard Adams work adapted to the screen so far is The Girl in a Swing (1988), which is a ghost story.

Watership Down (1999) was a short-lived animated tv series, produced by Martin Rosen. Watership Down (2018) was a CGI animated tv series remake from the BBC.

Trailer here