New Zealand/Germany. 2002.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Niki Caro, Based on the Novel The Whale Rider by Witi Ihimaera, Producers – John Barnett, Frank Hubner & Tim Sanders, Photography – Leon Narbey, Music – Lisa Gerrard, Visual Effects – The Vision Digital Team, Production Design – Grant Major. Production Company – South Pacific Pictures/ApolloMedia Filmproduktion/Pandora Film/The New Zealand Film Production Fund/The New Zealand Film Commission/NZ On Air.

Cast

Keisha Castle-Hughes (Paikea Apirama), Rawiri Paretene (Koro Apirama), Vicky Haughton (Nanny Flowers), Cliff Curtis (Porourangi Apirama), Grant Roa (Rawiri), Mana Taumaunu (Hemi)

Plot

In a rural New Zealand community, a baby daughter Paikea is born to Porourangi, the son of the Maori chief Koro. Paikea’s twin brother dies, along with her mother, and Koro is bitterly disappointed that he has no son to carry on the family tradition. Porourangi leaves and becomes an artist around the world. Growing up with her grandparents, Pai is hurt by her grandfather’s constant rejection of her. A return visit from Porourangi convinces Koro that it is time to choose a new chief. As he begins selecting from among the other boys of the tribe, Pai begins to learn the art of the taiha staff in secret. She starts to feel the deep mythic call of the family’s bond with the whales of the ocean. However, her grandfather constantly refuses to allow her to accept this because she is a girl.

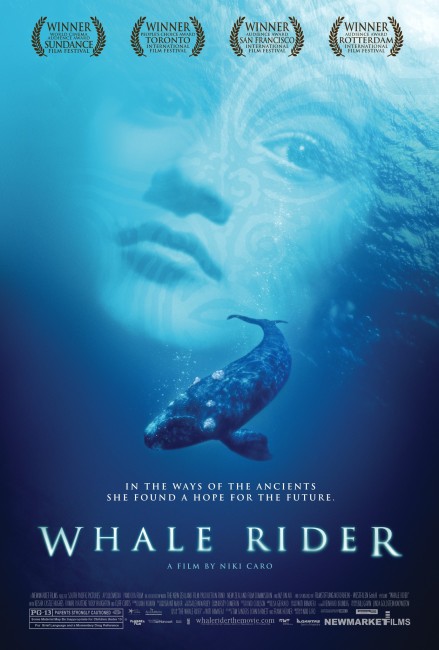

Outside of the Lord of the Rings brouhaha, Whale Rider was one of the most internationally acclaimed films to emerge from New Zealand in the 2000s – indeed, it was the most acclaimed New Zealand film since probably Peter Jackson’s own Heavenly Creatures (1994). Whale Rider won the People’s Choice Award when it premiered at the 2002 Toronto International Film Festival and went onto considerable acclaim at the 2003 Sundance festival and in international arthouse release.

The story builds slowly – and probably too meanderingly for Hollywood blockbuster standards. You can see where everything is going from the outset – in terms of Paikea’s inevitable triumph to inherit her destiny, her grandfather’s eventual admission that he is wrong, of who will be the one that retrieves the carved whale tooth from the bottom of the sea. Through all of this, the story does shine through. Paikea’s triumph and final assumption of the title role eventually becomes a moving and triumphal scene. Whale Rider is a film that is no small part given over to and carried by its actors. Particularly good is Rawiri Paretene as the grandfather.

As a film, Whale Rider sits halfway between the earnest deference towards biculturalism of the liberal Pakeha – while the cast are almost entirely all Maori, the film crew are almost entirely Pakeha (European New Zealanders) – and between the polishing of the picture postcard tourist shots and ritual aspects of Maori that cultural visitors are drawn to for international sales. The story is ever so dragged out of shape at times by the filmmakers apparent feeling the need to insert messages – about the high rate of smoking among Maori women, about healthy eating and a whole subplot that doesn’t happen about one child being neglected by a parent who has joined the gangs, all of which are concern issues among Maoridom. At times, Whale Rider cannot help but seem like one of the Ministry of Health posters in local doctor’s surgeries warning about lung cancer and heart disease among Maori.

It is interesting to make comparison between Whale Rider and Once Were Warriors (1994), the one other film about New Zealand Maori to attract attention on the international stage. Both Whale Rider and Once Were Warriors feature Cliff Curtis, both come from books by two Maori novelists to have made crossover success into mainstream acceptance in the ghetto of New Zealand publishing. Both Whale Rider and Once Were Warriors are also films that are concerned with the state of the modern Maori people and the erosion of Maoritanga (Maori culture).

In both films, we see a sharp crosscut of Maori down the lower end of the New Zealand socio-economic scale and a depiction of the problem that exists there with alcohol, drugs, gangs and parental neglect. Whale Rider is certainly kinder and more accepting of this than Once Were Warriors was. Once Were Warriors was based on a novel by Alan Duff, who has become notoriously outspoken in his message of tough self-reliance, in telling unemployed and poor Maori to get their act together.

Both are also films told principally from the perspective of a Maori woman who faces an angry or (here) sullen Maori man. Where Alan Duff and Once Were Warriors‘ message was for her to stand up and take reliance of her life into her own hands, Whale Rider is more genteel in that it sees the need of modern Maori to return to a sense of community and tradition. Although, considering that Maori tradition is a notoriously patriarchal one, Whale Rider does offer a considerably more liberal message – it is, after all, a film about challenging the traditional patriarchal nature of Maoritanga and cautiously suggests that Maoridom needs to import a little feminist equality if it is to survive in the modern world.

Similarities can also be made between Whale Rider and the little-seen also NZ-made The Silent One (1984). Both are films set in a small ethnic New Zealand Polynesian community (Maori here, the Cook Islands in The Silent One) and both centre around a child who is an alienated community outcast and eventually finds their identity by mystically communing with the creatures of the sea. There is also a number of similarities between Whale Rider and The Secret of Roan Inish (1994), which was about the Irish returning to their cultural heritage and rediscovering a mystical communion with creatures of the sea.

Actress Keisha Castle-Hughes became a surprise nominee for Best Actress at the 2003 Academy Awards, also becoming the youngest ever nominated actress at the age of thirteen.

After making her directorial debut here, Niki Caro went onto make North Country (2005) about a sexual harassment suit, returned to the fantasy genre with The Vinter’s Luck (2009) about a winemaker who makes a deal with an angel and made the non-genre true life sports film McFarland, USA (2015), the true-life WWII drama The Zookeeper’s Wife (2017) and the live-action remake of Disney’s Mulan (2020).

Trailer here