USA. 1939.

Crew

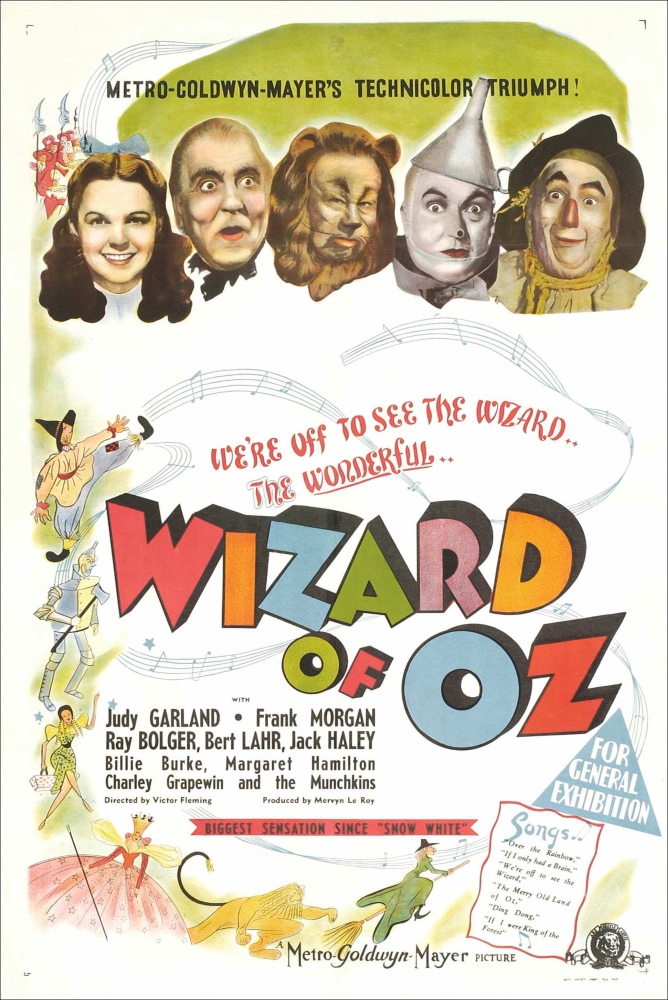

Director – Victor Fleming, Screenplay – Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson & Edgar Allan Woolf, Based on the Novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) by L. Frank Baum, Producer – Mervyn Le Roy, Photography (b&w & colour) – Harold Rosson, Music – Herbert Strothart, Songs – Harold Arlen & E.Y. Harbury, Special Effects – A. Arnold Gillespie, Makeup – Jack Dawn, Bob Schiffer, Charles Schram & Jack Young, Art Direction – Cedric Gibbons & William A. Horning. Production Company – MGM.

Cast

Judy Garland (Dorothy Gale), Ray Bolger (Scarecrow/Hunk), Jack Haley Sr (Tin Man/Hickory), Bert Lahr (Cowardly Lion/Zeke), Margaret Hamilton (Wicked Witch of the West/Elvira Gulch), Frank Morgan (Oz/Professor Marvel), Billie Burke (Glinda), Clara Blandick (Auntie Em), Charley Grapewin (Uncle Henry)

Plot

Young Dorothy Gale lives on a farm in Kansas with her Uncle Henry, her Auntie Em and her dog Toto. Suddenly, a tornado appears and whisks the entire house away while Dorothy shelters inside. She emerges to find the house has been deposited in the magical land of Oz where it has landed on and killed the Wicked Witch of the East. The dwarfish Munchkin natives cheer Dorothy for liberating them from the Witch. Dorothy only wants to return home. The Munchkins tell her that the only person able to help her do so is the Wizard of Oz who lives in the Emerald City. And so Dorothy sets forth on a journey to the Emerald City. Along the way, she gathers a group of companions – a scarecrow who wants to find a brain, a tin woodsman who wants a heart and a lion who desires courage. At the same time, the Wicked Witch of the West comes after Dorothy, wanting the magical ruby slippers that Dorothy took from her sister.

The Wizard of Oz has such a classic status in people’s minds that writing a review of it is almost an impossible task. It has such a revered place that picking holes in it is akin to offering suggestions as to how God might want to better run the world. More to the point, the film has been pored over so much so – entire volumes written about the making of it – that it feels almost impossible to say something new and original without treading over old ground. Well, here goes one effort …

The film is based on a book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) by former newspaper editor L. Frank Baum (1856-1919). The book was an immediate success upon publication. A musical stage adaptation was made in 1902 and the following year it was turned into a huge Broadway success. L. Frank Baum wrote thirteen other Oz books, where he expanded out and peopled the lands with all manner of bizarre creatures, as well as six tales for younger children. Baum had a great interest in theatre and also wrote three Oz plays. The Oz stories were adapted to film a number of times in the silent era with The Wizard of Oz (1908), The Wizard of Oz (1910), Dorothy and the Scarecrow in Oz (1910), The Land of Oz (1910) and The Wizard of Oz (1921), many of which are lost today. Baum also formed the Oz Film Manufacturing Company and oversaw three film productions, The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1914), The Magic Cloak of Oz (1914) and actually directed His Majesty, The Scarecrow of Oz (1914), which are still in existence today. The one other silent production still in existence is Wizard of Oz (1925), a version starring Oliver Hardy of Laurel and Hardy fame as the Tin Woodsman, although this is a slapstick comedy that varies widely from the book.

The Wizard of Oz has such classic status that the story surrounding it has become the stuff of legend, even urban legend. The production history was extraordinarily troubled, undergoing several changes of director, with Richard Thorpe, director of Night Must Fall (1937), numerous MGM Tarzan films, Jailhouse Rock (1957); George Cukor, director of Camille (1936) and The Philadelphia Story (1940); and King Vidor, director of Stella Dallas (1937) and The Fountainhead (1949), all having worked as director at some point, before Victor Fleming was decided upon – but even then Fleming had to curtail shooting and go off and work on another troubled production – Gone with the Wind (1939). Some of the original casting choices are fascinating to contemplate – Shirley Temple as Dorothy, W.C. Fields as The Wizard, Buddy Ebsen as the Tin Woodsman (in fact, Ebsen started shooting in the role but quit after having an allergic reaction to the makeup).

Stories about the making of the film are legendary. These range from the true – Margaret Hamilton was severely burned in a special effects accident; that Over the Rainbow was nearly cut from the film; that the studio fed Judy Garland uppers and downers to get her through the day’s shooting – to those that exist as urban legend – that a fluttering in the trees in one scene was a crewman hanging themselves on-set; that the little people portraying the Munchkins were often drunk on-set and engaged in orgies after hours; that a coat purchased in a thrift shop to be worn by Frank Morgan as The Wizard was found to have L. Frank Baum’s name in it; that there are a remarkable number of coincidences between The Wizard of Oz and the Pink Floyd album The Dark Side of the Moon (1973) when both are played alongside.

The film has gained an extraordinary fame – pieces of terminology from it – phrases like “Over the Rainbow,” “I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore, Toto,” have entered into everyday speech, while the term Munchkin has become a colloquialism for a small person. In an auction in 2000, Judy Garland’s ruby slippers were sold for $660,000, while the American Film Institute voted Over the Rainbow the No. 1 song from a movie.

The film makes a number of changes to the book. These include:-

- The Wicked Witch of the West is introduced much later in the book (only Chapter 12 out of a total of 24) – after Dorothy and the companions go to Emerald City and are despatched to kill her by The Wizard. By contrast, the film introduces The Wicked Witch from the point of Dorothy’s arrival in Munchkinland and adds her vendetta about the ruby slippers to turn her into much more of an ongoing nemesis throughout.

- What we know on screen as Glinda the Good is actually two characters in the book – the Witch of the North who we meet in Munchkinland and is also a Munchkin, and Glinda, the Witch of the South, who the party travel to visit after The Wizard departs. In the film, these have been condensed into a single character.

- Both the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodsman get backstories that have been excised in the film.

- No doubt due to the fact that it looks prettier on screen, Dorothy’s gets ruby slippers instead of silver shoes.

- Upon the group’s arrival at the Emerald City, The Wizard has different appearances for each of the companions – as a giant head, a woman, a beast and a ball of fire, which are all later given mundane explanations as stage trickery.

- The film dumps many of the supplementary encounters on the initial journey down the Yellow Brick Road, where we also meet the Kalidahs (creatures with the body of a bear and the head of a tiger) and the Queen of the Field Mice, and during the journey they undergo to the South to meet Glinda, which includes encounters with people made of china, The Hammerheads and the armless Quadlings. (The two encounters that are kept are those with the field of poppies and the enchanted trees).

- Also dropped are the other creatures the Wicked Witch sends against the party – bees, wolves and the Winkies – and the cap that controls the flying monkeys.

Despite trimming many of these bits, the film is very faithful to the essence of L. Frank Baum. It does take the single idea from the 1925 film of there being a mirror between Kansas and Oz where the real world scenes contain analogues of the characters in Oz. In the opening scenes in Kansas, we see all the elements and conflicts being symbolically laid down amongst the real world counterparts of the companions, The Wicked Witch and The Wizard.

There have also been an extraordinary number of interpretations of the meaning of the book and film. The most prevalent of these is one put forward in 1964 by high-school economics teacher Henry M. Littlefield that the L. Frank Baum book is an allegory for the state of American politics circa 1896 – the symbolism of Yellow Brick Road and silver slippers represents the heated debate over the move from gold to silver coinage at the time; the puffed-up Wizard of Oz stands in for President William McKinley; The Wicked Witch is an allegory for the cutthroat stranglehold exerted by the banks and railroads; the Tin Woodsman and Scarecrow stand in for the economically downtrodden steelworkers and farmers; and that the Munchkins and monkeys represent the American Indians. This theory is extraordinarily prevalent and has even been taught at a number of universities.

One is slightly dubious about the theory – after all, whether L. Frank Baum’s personal politics reflect this interpretation is an issue for debate, some of his newspaper editorials would suggest that his sympathies might have been to the contrary. Furthermore, this theory highlights The Wonderful Wizard of Oz but places no emphasis on any of the other Oz books that Baum wrote, after which the strength of the theory becomes considerably more dissolved. Not to mention that this interpretation is one that is heavily swayed towards the film version – the characters and creatures that have been cut from the story by the film are given no place in Littlefield’s theory.

Another theory regarding The Wizard of Oz is that it represents an allegory for world politics circa 1939 – The Wicked Witch as Adolf Hitler, the division between East and West representing the European war effort, sepia-toned Kansas as Depression-era America – but this neglects the fact that the film has been very closely taken from the L. Frank Baum book, which set all of these things in place some four decades before World War II. Not to mention the fact that the film was released before World War II was actually declared, where the USA took an isolationist policy to the War until being dragged in after Pearl Harbor in 1941.

The film itself is a colourful, sparkling fantasy. Surprisingly, considering its revered status subsequently, it was considered a White Elephant at the time of its release and not a financial success for many years. The film’s classic stature is something that grew following its’ airing on tv, which began in the 1950s. The story was earlier incarnated as a Broadway musical and, although the film is not related to that version, the film’s roots remain firmly in the Broadway musical. It is never a film that is particularly convincing – the actors play to the camera, it is clearly stagebound with obvious matte paintings and painted backdrops to stand in for Oz, while even the relative reality of Kansas is a studio-stylised Kansas. The wilful and obvious artificiality somehow works for the film. The actors have a conviction that propels the story up past its fuzzy feelgood sentiments with a wholehearted conviction. The film has a boisterous energy that it is hard not to be caught up in, despite the relative corniness of some of it.

You cannot help but be impressed by the size, splendour and above all the colour. It is important to note that The Wizard of Oz was made in Technicolor at a time when almost all films were made in black-and-white. The sheer lavishness of the restoration prints seen today is quite overwhelming – such colour must have had an untold greater effect coming as it did in the era of predominating black-and-white. At times, it is almost as though the film is a celebration of all the possibilities that colour can offer on screen. To create contrast, the initial scenes in Kansas come in black-and-white – when Dorothy opens the door out into Munchkinland, the film bursts into colour amid much singing, dancing and some amazingly vibrant sets and costumes. It is almost impossible for people today to grasp the dazzling effect this would have had for audiences of the day.

The Wizard of Oz was made as a rejoinder to the huge success that Walt Disney had had a couple of years earlier with his first animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and was the greatest leap of the fantastic imagination that Hollywood had made in live-action up to that point. There had been adventure fantasies like the Douglas Fairbanks The Thief of Bagdad (1924) and the same fabulism had been tapped in the flop version of Alice in Wonderland (1933), but it took The Wizard of Oz to genuinely dream of magical lands where nonsense plays out in garish colour and things exist on the level of a fairytale. It set a fantasy standard and even decades later films like Pufnstuf (1970), Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971) and How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000) still take from The Wizard of Oz in their absurdist conjurations of nonsense imagination. Indeed, without The Wizard of Oz, there would probably be no Dr Seuss.

The Wizard of Oz is perhaps the nearest that we have to a genuine American fairytale mythology. Many of the interpretations listed above – about the story being a parable of turn of the 20th Century politics or Wartime-era international relations – get caught up in the amateur symbolist’s trap of trying to find analogies for everything that happens and leaving nothing down to authorial whim or the dictates of plotting.

If anything, the film/book is about the great American myth of self-actualisation. It is about the allegorical search for courage, intelligence and heart. The ending of the film comes to the sentimentally banal realisation that these are things that lie within one and that all that we need to do is to recognise them. The farm in Kansas is the absolute ideal of home, hearth, purity and a loving family. Part of what makes The Wizard of Oz such a classic is that Dorothy’s desire to return home where life is loving and far more simple is the essence of what traditional Americana venerates – there have been few more pure-hearted and unabashedly sentimental evocations of this on the screen. The film reaches the conservative realisation that despite the magical and amazingly colourful world out there that there is no place like home and one’s family – as Judy Garland says, “If I ever go searching for my heart’s desire, I’ll never go looking any further than my own backyard.”

Arguably, The Wizard of Oz is also a film about the disillusionment with politics. It holds a certain cynicism about the people in power – that they are frauds, will fool or let you down and that one is better off trusting in one’s own natural abilities and inner strengths. The great and revered leader turns out to be a charlatan and all that is ultimately needed to get by is the simple abilities held within by the ordinary people of the world. If you read the book, another interpretation may just as equally say something about the gullibility of the people and how willing they are to believe what they are told – The Wizard convinces the party that they all have the attributes they seek within themselves all along and even when he is exposed continues to use simple tricks to convince the party that they are actually receiving something by giving them mundane tokens to represent heart, brains and courage. Moreover, The Emerald City is only ever magical when people put on green-tinted glasses that they have been fooled into wearing and The Wizard makes his departure without the people ever finding out that they have been hoodwinked.

There have been a number of sequels to the film but no direct remake as yet. The nearest there has been to a remake was The Wiz (1978), which was based on a popular Broadway musical, and repopulated the story with a Black cast including Diana Ross as Dorothy and Michael Jackson as The Scarecrow and with New York City standing in for Oz; and The Muppets’ Wizard of Oz (2005), which had the Muppets playing the various characters. Also of interest was Oz (1976), an obscure Australian film that transplanted the story to present-day Australia where Dorothy is a rock groupie who gets a bump on her head and sets out on a journey to meet The Wizard – a glitter rocker – where the companions are surfers, bikers and gay fairies; the tv mini-series Tin Man (2007), which translates the story into science-fiction terms, and the tv series Emerald City (2017), which offered a more adult, reworked dark fantasy. At one point, John Waters was purported to be contemplating a satiric remake, Dorothy the Kansas City Pothead.

In the sequel department, there was the animated Journey Back to Oz (1974), which had the novelty of featuring Judy Garland’s daughter Liza Minelli voicing the part of Dorothy. Disney made the quite good live-action sequel Return to Oz (1985), which was condemned at the time and a flop because it discarded the musical element, returned to the L. Frank Baum books and was surprisingly dark in tone; Sam Raimi’s prequel Oz: The Great and Powerful (2013), which tells origin stories of The Wizard and the Wicked Witch of the West; and Wicked: Part 1 (2024) and Wicked: For Good (2025), a two-part adaptation of the hit Broadway musical that tells the origin story of the Wicked Witch. There was also the low-budget The Witches of Oz (2011), which is a contemporary sequel, and the animated Legends of Oz: Dororthy’s Return (2014).

Other spinoffs include Tales of the Wizard of Oz (1961), an animated tv series adapting Baum stories, which lasted for 150 episodes; Return to Oz (1964), an animated special from Rankin-Bass; The Wizard of Mars (1965), which translated the story into sf terms; The Wonderful Land of Oz (1969), a reportedly incredibly bad theatrical sequel from adult filmmaker Barry Mahon; a Turkish adaptation, The Turkish Wizard of Oz (1971); Oz (1980), a Japanese-made short animated sequel; The Marvelous Land of Oz (1981), a live-action tv adaptation of the second of Baum’s books; a further feature-length Japanese animated adaptation The Wizard of Oz (1982); a 1984 live-action adaptation that sets the story in contemporary Brazil; a similar Mexican adaptation around the same time (1985); a series of Canadian animated adaptations of the Baum stories from director Gerald Potterton – The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1987), The Marvellous Land of Oz (1987), Ozma of Oz (1987) and The Emerald City of Oz (1987); a Japanese animated tv series The Galaxy Adventure of Oz (1990), which relocated the story as a space opera; Hakosem (1994), an Israeli version; The Wizard of Oz in Concert (1995), a tv special that reworked the music of the original and featured Jewel as Dorothy; The Wizard of Oz on Ice (1996), a tv special that re-enacted the story with ice skaters; Virtual Oz (1996), an animated children’s film from Hyperion Pictures that relocates Oz in Virtual Reality and a series of sequels, which also feature several non-Oz Baum characters, Christmas in Oz (1996), The Nome Prince and the Magic Belt of Oz (1996), Toto Lost in New York (1996), Journey Beneath the Sea (1997), The Monkey Prince (1997), The Return of Mombi (1997) and Underground Adventure (1997), as well as a tv series The Oz Kids (1996); a Canadian animated sequel Lion of Oz (2000); and the animated The Patchwork Girl of Oz (2009). There was even the dire Chevy Chase comedy Under the Rainbow (1981) set around the comic shenanigans of the little people playing the Munchkins behind the scenes during the making of the film. Also of note is Apocalypse Oz (2006), a film that bizarrely mixes The Wizard of Oz and Apocalypse Now (1979).

An enormous number of films since have also borrowed or referenced The Wizard of Oz. John Boorman’s pretentious science-fiction film Zardoz (1974) borrows its title from The Wizard of Oz, using the notion of a fearsome leader who is all smoke and mirrors as a complex metaphor; David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990) and the horror film YellowBrickRoad (2010) has a number of surreal Wizard of Oz allusions; the Wicked Witch and the Flying Monkeys make a guest appearance in The Lego Batman Movie (2017) and Dorothy and companions appear in The Lego Movie 2 (2019); there is a strange erotic restaging in Liquid Dreams (1991); and one can also find references in The Revenge of the Teenage Vixens from Outer Space (1986), Spaced Invaders (1990), Highlander II: The Quickening (1991), Twister (1996), Contact (1997), The Matrix (1999), Robots (2005), AE: Apocalypse Earth (2013), Ghost in the Shell: Arise (2013-4), Sharknado: The 4th Awakens (2016) and Robot Dreams (2023).

The film’s fame has also spread into literature – Philip Jose Farmer wrote A Barnstormer in Oz (1982), which wittily deconstructs the Baum books; no less an acclaimed figure than Salman Rushdie wrote The Wizard of Oz (1992) interpreting the meanings of the story, and there was Gregory Maguire’s novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West (1995), which was later turned into a massively successful Broadway musical Wicked (2003) by Stephen Schwartz, both retelling the story from the Wicked Witch’s point-of-view. The influence has even spread into popular music with Elton John naming his most famous album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (1973) and with the popularity of a mid-80s group called Toto.

Victor Fleming also directed a number of genre films including the Spencer Tracy version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941) and the afterlife fantasy A Guy Named Joe (1943). Fleming is probably best known for Gone with the Wind and dramas like Captains Courageous (1937) and the Ingrid Bergman Joan of Arc (1948).

Trailer here