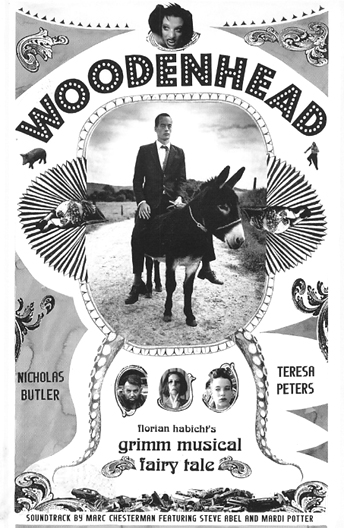

New Zealand. 2003.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer – Florian Habicht, Photography (b&w) – Christopher Pryor, Music – Marc Chesterman, Additional Music – Steve Abel, Foamy Ed, Mardi Potter & The Ratana Brass Band, Art Direction – Teresa Peters. Production Company – Pictures for Anna.

Cast

Nicholas Butler (Gert), Teresa Peters (Plum), Tony Bishop (Goerdel), Matthew Sunderland (Gustav), Warwick Broadhead (Hugo), David Hornblow (The Tramp), Mardi Potter (Kathy the Waitress), Henry Lee (Ringmaster)

Voices

Steve Abel (Gert), Mardi Potter (Plum), Lutz Halbhubner (Goerdel/Radio DJ), Matthew Sunderland (The Tramp), Vanessa Rhodes (Kathy the Waitress), Margaret Mary Hollins (Narrator)

Plot

Gert, a garbage man at the Woodland dump, accepts the task of driving his boss Hugo’s daughter Plum to her wedding in neighbouring Maidenwood. On the way there, Gert’s car breaks down and he and Plum are forced to continue on by donkey. They become lost in the woods and, after divesting most of their clothing to leave a trail, they are overcome by romantic desire when they spend the night at a cottage. Continuing on the next day, Plum is abducted by Gustav, a mute strongman who has escaped the circus and now desires a wife, while Gert runs afoul of the hunter Goerdel.

For one reason or another, New Zealand has gained a reputation as a cinematic fantasy landscape. Various international productions such as George Lucas’s Willow (1988), tv’s Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (1994-9) and Xena: Warrior Princess (1999-2001) and The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005) have sought to exploit the imagery of clean, green untouched landscapes. Of course, the New Zealand fantasy landscape was propelled into high gear by Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, with the country even renaming itself Middle-Earth and spinning off a tourist industry from such.

New Zealand fantasy is also a dual-edged coin. While on one hand, the pristine openness of the landscape is sought as a stage for epic adventure fantasy by international filmmakers, on the other, local filmmakers when venturing into fantasy tend to look at it as though the rawness were something darkly oppressive and primordial. Look at films such as The Lost Tribe (1985) in which the Fjordland locations become something haunted in their primality; Vincent Ward’s visually stunning quasi-fantastical Vigil (1985), which is a like a single visual tone poem to the raw magic of the Earth, and his subsequent The Navigator: A Mediaeval Odyssey (1988) where the modern world broods with mediaeval imagery; the oppressive silence that haunts Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth (1985); even Harry Sinclair’s The Price of Milk (2000), which found an appealingly absurdist Magical Realism amongst the cow pads.

These disparate strands of the New Zealand fantasy landscape find their meeting point in Woodenhead. Woodenhead was made by 28 year-old Florian Habicht. Habicht is German-born but has been a New Zealand immigrant since the age of eight. Both strands of Habicht’s backgrounds also find a meeting point in Woodenhead. Habicht draws upon a distilled version of Grimm fairytales and claims inspiration from films such as Volker Schlondorff’s The Tin Drum (1979), a Magic Realist work where similarly twisted repressive forces keep making themselves apparent. Yet on the other hand, Habicht also intuitively taps into New Zealand filmmakers’ sense of an oppressively primal landscape that broods with all manner of outward expression of inner turmoils. The North Island landscapes have been shot in black-and-white and the bared open fields and native forests brood with a forebodingly stilled ominousness.

Woodenhead is a Grimm fairytale of sorts. It is clearly also a deconstructed fairytale where the modern world and the landscape of fairytale combine in peculiar ways – where the hero of the fairytale takes the princess heroine to her destined wedding alternately in a broken down Humber and by donkey, where they stop for the journey along the way at the classic piece of Kiwiana – the roadside pie cart.

Woodenhead feels like Florian Habicht has distilled fundamental elements of fairytales – the journey lost in the woods from Hansel and Gretel, the deserted cottage with the food laid out from Goldilocks, the swarthy woodsman out to kill the hero/heroine from Snow White, the magic beans from Jack and the Beanstalk – and run it through with something akin to the surrealistic aesthetic of an Eraserhead (1977) or perhaps the kitsch of Canadian director Guy Maddin.

There are some hysterically weird scenes – the love scene between Gert and Plum where Habicht manages to turn the bizarre image of he feeding her from a baby’s bottle into something erotic, before ending on one of the most hysterically deadpan love scenes – all with the camera turning topsy-turvy as Gert’s bare butt frenetically humps away at her, after which the narrator coyly informs us “Plum and Gert had kissed for the first time”; to the bizarre encounter with a priest who tortures Gert in a field by having a goat nibble his ankles; and the charmingly wacky image at the end of a trio of girls in bloomers lying on their back on a beach conducting a dance with their legs up in the air.

What is unique about the way that Woodenhead was made is that Florian Habicht recorded the entire soundtrack before he shot any of the film, something that is probably a world-first for any non-animated film. This has a striking effect – the actors seem to perform independent of their voices. Voices will come on the soundtrack but the actors’ mouths don’t move just like a cheaply dubbed Italian or Japanese B movie. This has a weirdly disjunctive effect – it is surely the cinematic equivalent of thought balloons in a comic strip panel. (In the press notes for Woodenhead, Habicht recounts a highly amusing anecdote about how he received the idea in a dream in which he saw two angels descend from Heaven who turned out to be Milli Vanilli (the infamous 1980s pop group who revealed they had had their voices dubbed) who told him that he must prerecord the voices for the film).

More to the point, this is also something that allows Habicht to cast one set of actors for the way they look and a different set of actors to provide the voices that are right for the part. The actors have all been chosen for the strikingly physicality of their appearance – Habicht’s girlfriend Theresa Peters plays the princess Plum, where her long face and strikingly bony, almost masculine, features have a cool, distantly aloof beauty; hero Nicholas Butler has been chosen for his blankly impassive appearance, where all the expressiveness of his character is denoted by the wrinkling of his prominent forehead; and in the part of Goerdel, Tony Bishop has been deliberately cast as the cliché image of a swarthy criminal.

Trailer here