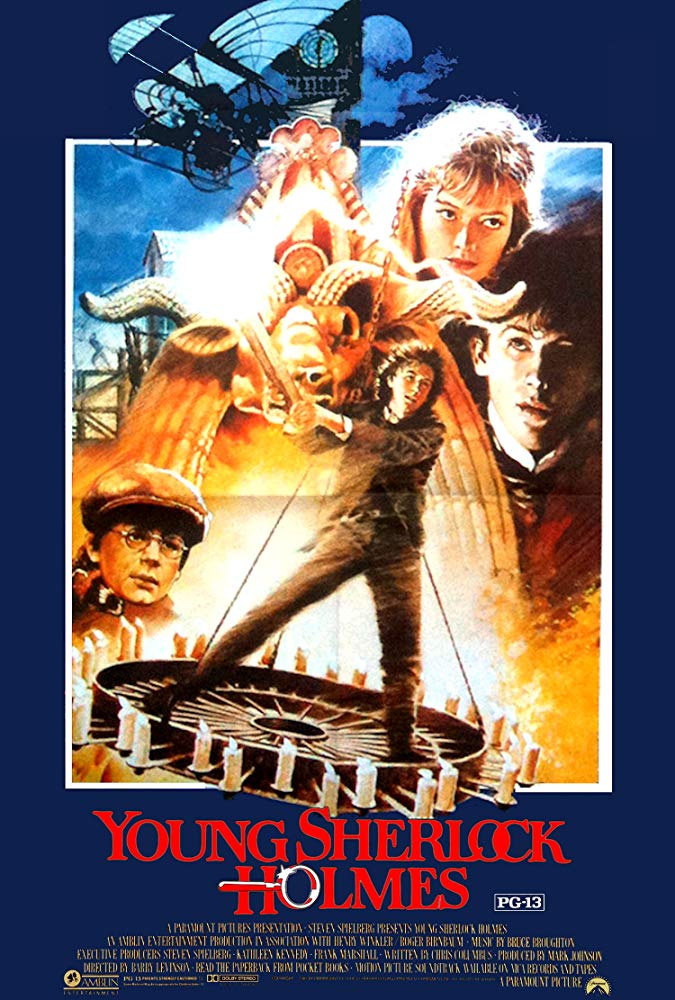

aka The Pyramid of Fear; Young Sherlock Holmes and the Pyramid of Fear

USA. 1985.

Crew

Director – Barry Levinson, Screenplay – Chris Columbus, Producer – Mark Johnson, Photography – Stephen Goldblatt, Music – Bruce Broughton, Visual Effects – Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Dennis Muren), Production Design – Norman Reynolds. Production Company – Amblin.

Cast

Nicholas Rowe (Sherlock Holmes), Alan Cox (John Watson), Sophie Ward (Elizabeth Hardy), Anthony Higgins (Rathe), Earl Rhodes (Dudley), Nigel Stock (Professor Rupert T. Waxflatter), Freddie Jones (Cragwitch), Susan Fleetwood (Mrs Dribb), Roger Ashton-Griffiths (Inspector Lestrade)

Plot

A teenage John Watson arrives at a new boarding school. He is placed in the dormitory next to the adolescent Sherlock Holmes where he is amazed by Holmes’s brilliant mind and deductive powers. The two rapidly become friends. A scheming school rival then plants a piece of paper that has Holmes accused of cheating on an exam and he is expelled. As Holmes prepares to leave, he and Watson become involved in solving several murders being conducted by hooded figures using deadly hallucinogenic blow darts. Behind this is the evil, human-sacrificing Egyptian cult of Ramaytan, whose numbers secretly include several members of the teaching faculty. As Holmes and Watson uncover, they have come to seek revenge on several men who razed their village to build a hotel.

During the 1980s and before he created his own studio (DreamWorks SKG), Steven Spielberg acted as executive producer on a number of films made by other directors under his Amblin production company name. There were notable successes among these – particularly Gremlins (1984), Back to the Future (1985) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). Among these Spielberg-produced films, Young Sherlock Holmes was one entry from the Spielberg stables that received a poor reception from critics – “Indiana Holmes”-type reviews – and audiences alike and where the Spielberg name was not enough of a draw for once. Sad, because that is not the reception the film deserved at all.

With Young Sherlock Holmes, Spielberg handed direction over to Barry Levinson. Levinson was then only known for modestly acclaimed films such as Diner (1982) and The Natural (1984) and had not matured into the refreshingly intelligent director that he would become over the next few years. Ahead for Levinson would be Good Morning Vietnam (1987), Rain Man (1988), Bugsy (1991), Sleepers (1996), Wag the Dog (1997) and occasional genre forays such as the wonderfully offbeat fairytale Toys (1992) and the Michael Crichton adaptations Disclosure (1994), a thriller about workplace sexual harassment, Sphere (1998) about the discovery of a UFO and the environmental disaster Found Footage film The Bay (2012).

Levinson worked from a script by Chris Columbus, who was then a writer for hire at Amblin and had also tuned the scripts for Gremlins and The Goonies (1985). Columbus would of course later become a director of some commercial success, albeit frustratingly bland output, with the likes of Home Alone (1990), Mrs Doubtfire (1993), Bicentennial Man (1999), Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001), Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002), Percy Jackson & The Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010) and Pixels (2015).

The biggest problem with Young Sherlock Holmes is that it is very much a Sherlock Holmes that has been worked over by Steven Spielberg and Industrial Light and Magic. As other critics noted, it is a Sherlock Holmes that seems to owe more to Indiana Jones than it ever does to Arthur Conan Doyle. However, under Barry Levinson’s hand, this is a marriage that works surprisingly well. As Holmes pastiches go, the story certainly lacks the inspiration of The Seven Per Cent Solution (1976), the modernised Sherlock (2010– ) or even Murder By Decree (1979), but I far preferred it to the Guy Ritchie-Robert Downey Jr Sherlock Holmes (2009).

Chris Columbus’s script is not without its graces, nor attention to the trivia of the mythos – the end credits even go so far as to painstakingly point out that according to Arthur Conan Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson never met until later life and this is but a fictionalisation of such a meeting. (Buffs should wait until the very end of the credits for a surprise appearance by Professor Moriarty).

The failing of the film is equally that it is rooted in adventure more so than it ever is in deduction – Nicholas Rowe’s Holmes has a couple of scenes throughout bringing his razor-sharp brilliance to bear but, unlike any Conan Doyle story, the climax is not the unveiling of a whodunnit but a swordfight. Furthermore, some of the revelations of the cult members’ identities seem contrived with a clumsiness that is most un-Doyle like.

On its own terms, Young Sherlock Holmes works beautifully. It is a gorgeously made film – from the wonderfully ambient candlelit photography to the rafter-skimming symphonic score and the exceptionally fine period design, which moves from Waxflatter’s rickety workshop to an entire series of docks where the ice has been frozen over. Barry Levinson directs with a perfect balance of adventure and romance – the climactic swordfight is a real corker.

Industrial Light and Magic conduct some of their best ever work during this period in the occasionally superfluous but never less than entirely captivating menagerie of animated gargoyles, chicken dinners returned to life, attacks by sword-wielding stained glass windows and ambulatory delights from a cake shop. Nicholas Rowe has just the right touch of imperiousness as Holmes. Sophie Ward has an incredible loveliness, even if the film’s romantic element is underdeveloped.

In a cute piece of fanservice, thirty years later Nicholas Rowe was also cast as the movie version of Sherlock Holmes in Mr. Holmes (2015).

Trailer here