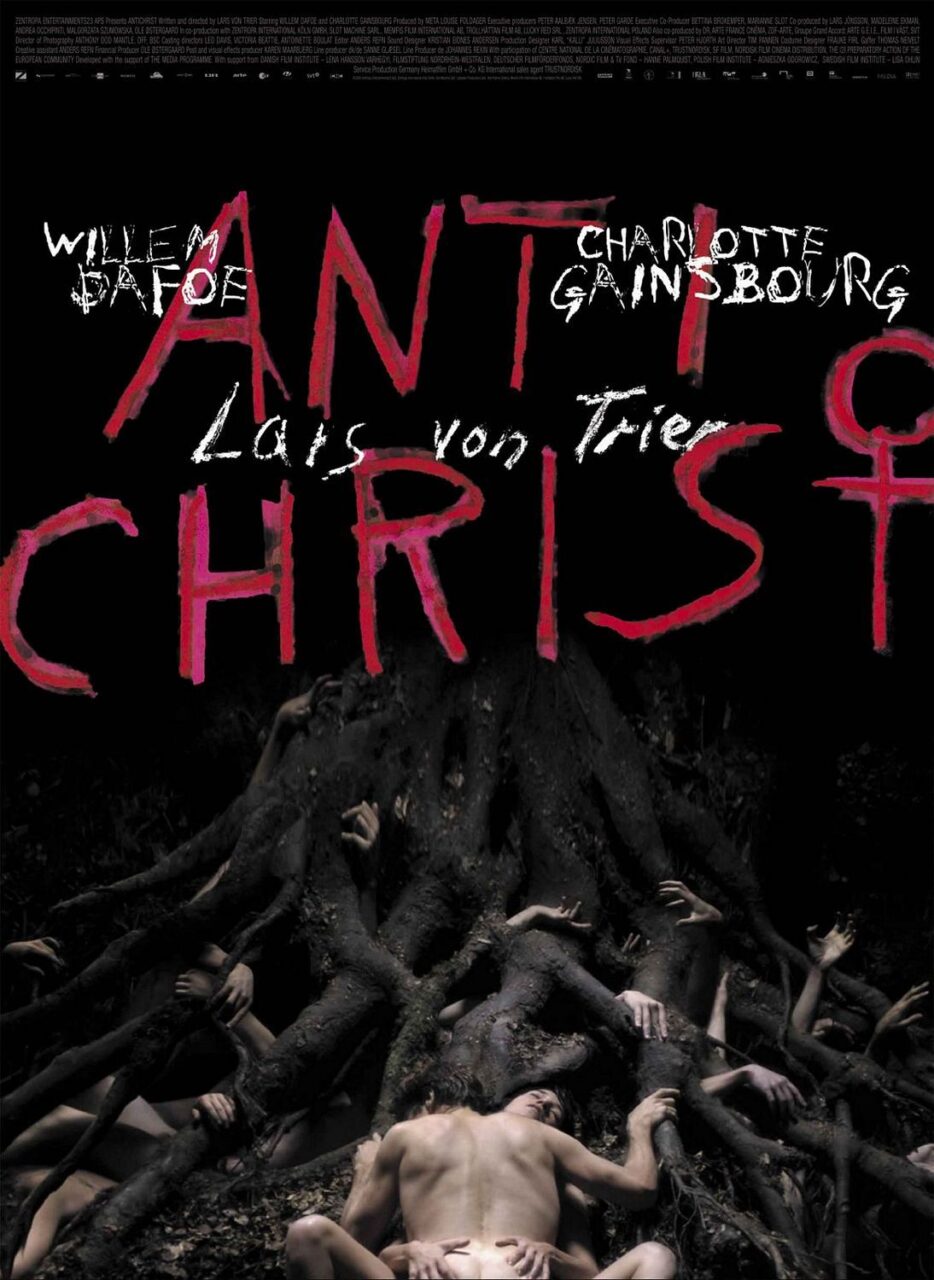

Denmark/Germany/France/Sweden/Italy/Poland. 2009.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Lars von Trier, Producer – Meta Louise Foldager, Photography (colour + b&w) – Anthony Dod Mantle, Visual Effects Supervisor – Peter Hjorth, Visual Effects – Filmgate & Platige Image, Special Effects Supervisor – Erik Zumkley, Makeup Effects – Sods ApS (Morten Jacobsen, Thomas Foldberg), Production Design – Karl Juliusson. Production Company – Zentropa Entertainments/Zentropa International Koln/Slot Machine/Memfis Film International/Trollhattan Film AB/Lucky Red/Zentropa International Poland/DR/Arte France Cinema/ZDF-Arte Group/Groupe Grand Accord: ARTE G.E.I.E./Film i Vast/WDR/Sveriges Television.

Cast

Willem Dafoe (He), Charlotte Gainsbourg (She)

Plot

A husband and wife are shattered after their young son stumbles out a window and falls to his death while they were having sex in the shower. She is hospitalised, unable to cope with the grief. He is a psychologist and insists that she stop taking the prescribed drugs, come home with him and process the emotions with his support. As he tries to guide her, he gradually learns that her greatest fear is of Eden Forest. To help her confront her fear, he takes her away to stay at a cabin in the forest. Once there, she gradually starts to fall apart mentally, believing that all womankind is fundamentally evil. This culminates in a nightmare of violence where she knocks him out, drills through his shin and attaches a grindstone to his ankle.

For the better part of a decade now, whenever someone has asked me the question “who is the best director in the world?” I have always nominated Lars von Trier (at least among living directors). The Danish von Trier is one of cinema’s constant tricksters. He has a finely tuned sense of black humour and loves to make films for the sheer outrage that will result – see The Idiots (1998), a black comedy about people who pretend to be mentally handicapped, or his delve into US slavery in Manderlay (2006). Lars von Trier is also an eminent stylist – see the extraordinary visuals of Zentropa/Europa (1991) – but on the other side of the coin is the director who devised the Dogme manifesto that threw all visual style out the window and issued filmmakers a challenge that took filmmaking back to raw essentials stripped of all artifice, while Dogville (2003) and Manderlay are films made without any sets, just bare stages with props and chalk marks. von Trier is confrontational – his films have an extraordinary amount to say and not many of them come with happy endings. What people often do not see beyond the theatrics is that his films are often genuinely emotionally shattering – see Breaking the Waves (1996), Dancer in the Dark (2000). Try to find another director in the world that has such a unique and distinctive voice.

Lars von Trier has broached genre material on several occasions. His first two feature films were The Element of Crime (1984), an artily obscure detective story set in a future Europe, and Epidemic (1987), part autobiography about the frustrations of filmmaking, part drama about a plague and eventually a weird meta-fiction. von Trier also co-directed the hit Danish tv series The Kingdom (1994) and its sequel The Kingdom II (1997) set in a haunted hospital and containing a side-splittingly rich vein of black comedy. Lars von Trier’s most acclaimed film is probably Breaking the Waves, an extraordinary and emotionally devastating film about a woman’s masochistic sacrifices for her husband that eventually arrives at a fantastic climax. Subsequent to Antichrist, von Trier also made the End of the World film Melancholia (2011) and the serial killer film The House That Jack Built (2018). von Trier’s Zentropa Entertainments production company has also backed or co-produced a number of European productions – see below for their other genre entries.

Antichrist comes three years after Lars von Trier’s previous film, the black comedy The Boss of It All (2006). For von Trier, the period in between was punctuated by a black depression during which he thought that he would never be able to make another film again. His therapist advised him to channel his feelings onto film. The resulting film Antichrist premiered at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival where it was subject to audience walkouts and then awarded a special jury prize for ‘its misogyny’. Fairly much everywhere it played subsequently, Antichrist polarised audiences, causing outrage for its misogyny and shocking with its full-on scenes of genital mutilation. Even the title, which has nothing to do with anything that takes place in the film, seems intended to offend a certain religiously-minded sector of the audience. The irony of this is that while Antichrist was rejected by arthouse audiences, it gained a audience at horror movie festivals. If nothing else, it proved that controversy is always a good selling point.

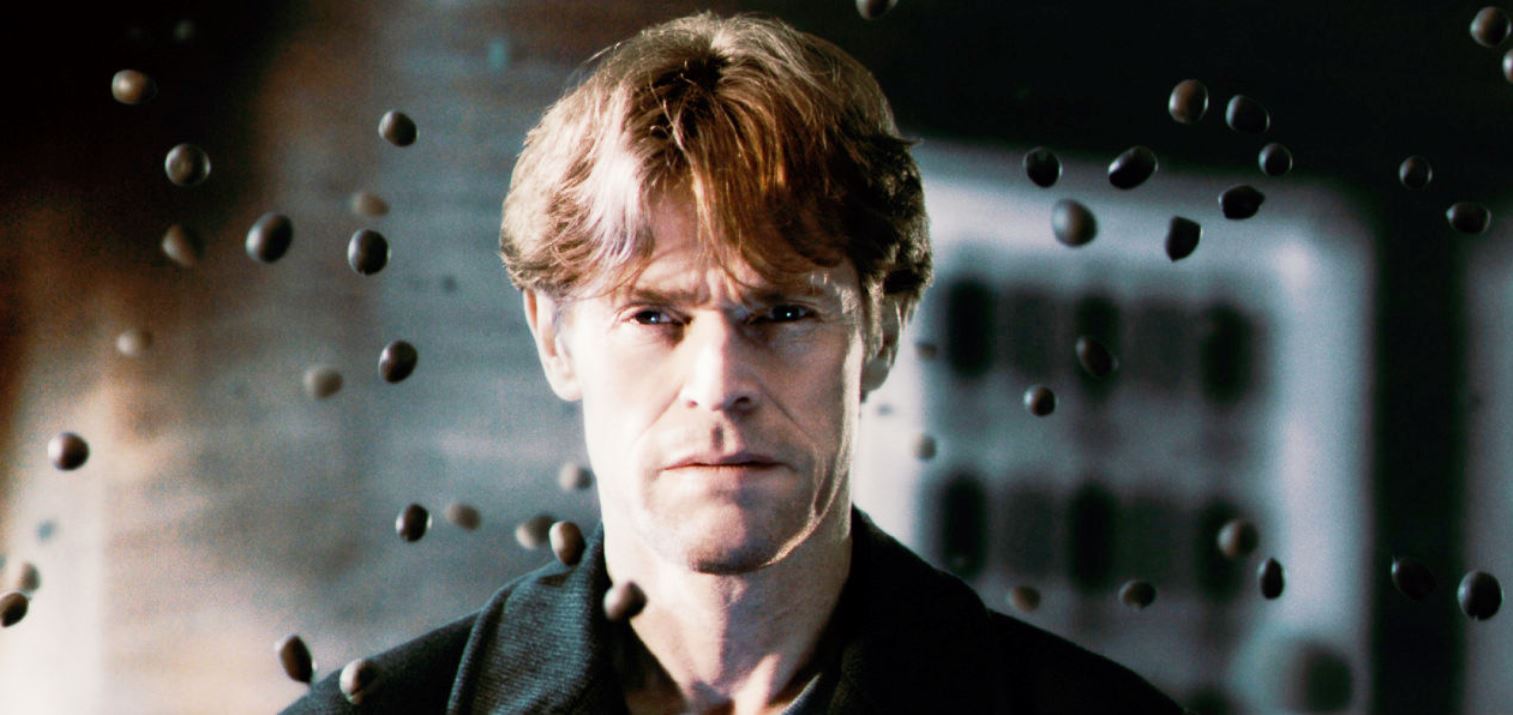

What these two different audiences (arthouse/festival crowds and horror fans) and their wildly polarised responses indicate is just how schizophrenic a work Antichrist is. The first half of the film, where we see psychologist Willem Dafoe patiently trying to coax wife Charlotte Gainsbourg through her grief, is far from horror movie territory. Lars von Trier’s tone here is calm and mild – the film comes in measured tones and is coolly photographed (in fact, von Trier’s composed shots and subdued lighting schemes during these scenes could not be further from the ragged Dogme look and sparse minimalism he has opted for in his last few films).

Beyond the character interactions, the background of the film is bare, stripped of supporting characters, while the lead characters are blank to the point they are not referred to as anything more than He and She. It is Lars von Trier setting a stage and allowing the bleeding pain of grief to spill out like some naked work of psychodrama. The nearest film you might compare Antichrist to during these scenes is Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1972). When he is making this type of film, Lars von Trier is capable of capturing an emotional rawness that is about as far away from the pat happy wrap-ups of American tv as it is possible to get. On the other hand, one finds it hard to think that horror movie audiences are likely to have much affinity for this section of the film.

Equally, the aspect that turned most mainstream audiences off was the second half where Lars von Trier readily deviates from what up until then had been a marital psychological drama into full-on Torture Porn territory. Charlotte Gainsbourg knocks Willem Dafoe out and then drills a hole through his left shin, whereupon he comes around to find that she has attached a grindstone to his ankle. After bashing his crotch with a rock, she masturbates him and he ejaculates blood. This culminates in a nasty climax that involves her lying down beside him and using a pair of scissors to cut off her clitoris. The result feels like two separate films – a European arthouse film that suddenly morphs mid-film into something like an intellectual Torture Porn film. There is also a minor amount of nudity, including some penetration shots as the film opens and others of Charlotte Gainsbourg furiously masturbating in the forest.

In all of this, I wish I could say that I had a clear of what Antichrist was about. It is a deeply unfathomable film. Though Willem Dafoe is supposed to be a psychologist and much psychological doubletalk is bandied throughout, what causes Charlotte Gainsbourg to go off the deep end and become psychotic is a good a guess as anybody’s. A mutilated talking fox appears partway through to utter the cryptic phrase “Chaos reigns” (also one of the chapter titles) at Willem Dafoe, although what this phrase or the fox’s presence means is equally unclear. Throughout the latter half, Charlotte Gainsbourg offers the fascinating opinion that “nature is Satan’s church” and that women are evil because nature controls their bodies, although whether this is her being deranged or something that Lars von Trier is trying to make a point about is unclear either.

In the end, Antichrist seems to be a film where Lars von Trier has worked out the troubling things that were going through his mind during his depression. If you can look upon Antichrist as venting of emotional bile, then it makes sense. Quite whether that is something that needed to be inflicted on audiences is another question altogether. In previous films – Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark, Dogville – Lars von Trier created almost saintly heroines whose purity and guilelessness ended up having them abused and taken advantage of by others around them. One gets the impression that during his therapy von Trier worked out whatever issues he had in regarding women as saintly sufferers and then took things to the opposite extreme. Indeed, von Trier even hired Danish journalist Heidi Laura to research a history of misogyny as background to the film.

Notedly, Antichrist comes at almost opposing contrast to Lars von Trier’s earlier Medea (1988) where a woman was driven to similar lengths of ultra-violence after her husband abandons her for another woman. However, where von Trier’s sympathies were wholly for Medea (who went to even greater extremes than Charlotte Gainsbourg), here the woman is regarded as deranged and eventually only worthy of despatch.

It is hard to fathom what Lars von Trier is trying to say about women in the film (or even if he means any of it seriously). At face value, the upshot of the film seems to be setting Willem Dafoe up as a calm, rational psychologist (indeed this is the only characterisation that Dafoe gets) and for Charlotte Gainsbourg to exist almost as an object lesson to demonstrate that therapeutic techniques are ineffectual in dealing with real pain. Willem Dafoe’s character arc seems to pass through patiently rational calmness and trying to maintain his cool through her increasing derangement, before losing it altogether and ultimately strangling her.

von Trier makes radical metaphors here – throughout Charlotte Gainsbourg has identified herself with nature and sees it as a malevolent force but the end coda as Willem Dafoe leaves the cottage and the frame bursts into hyper-realised black-and-white shows that the balance of nature appears to have been harmoniously restored, as though the whole world is in sympathy with his despatch of such feminine irrationality. The end upshot message that von Trier seems to have Willem Dafoe deliver to Charlotte Gainsbourg is “I’ve done my best to help you sort it out. I give up,” while the culminating end is delivered as a loud and clear equivalent of a “shut the fuck up, woman.”

Lars von Trier’s other films of genre interest as a director are:– the decayed future film noir The Element of Crime (1984); Epidemic (1987), a peculiar meta-fiction about filmmakers making a film about a plague and hypnotism; the black comedy tv mini-series’ The Kingdom (1994) and The Kingdom II (1997) set in a haunted hospital, which were both cinematically released internationally; Breaking the Waves (1996), an emotionally devastating film about a woman’s masochistic sacrifices for her husband, which eventually arrives at a fantastic climax; the End of the World film Melancholia (2011); the serial killer film The House That Jack Built (2018); and The Kingdom: Exodus (2022). Zentropa Entertainments other films of genre note are:- the Icelandic quest Cold Fever (1995); the Swedish fairytale The Glassblower’s Children (1998); the surreal old dark house thriller Impotence/Powerlessness (1998); Possessed (1999), a plague film about The Devil returning at the Millennium; Kat (2001), a horror film about a possessed cat; the Dogme film Truly Human (2001) about an imaginary man becoming real; The Last Great Wilderness (2002), a Gothic thriller set in the Scottish Highlands; Thomas Vinterberg’s near-future romance It’s All About Love (2003); In Your Hands (2004), a Dogme film about miracle healing prison inmate; the remarkable puppet fantasy Strings (2004); the ghost story Behind External Calm (2005); the dark reality-twisting Norweigian film Next Door (2005); Princess (2006), an animated film about an anti-porn vigilante; the satirical dystopia How to Get Rid of Others (2006); the fantasy Island of Lost Souls (2006); the horror film Echo (2007); Through a Glass Darkly (2008) about a girl receiving a mysterious visitation; the animated Dystopian film Metropia (2009); and Perfect Sense (2011) set in a world where people are losing their sensory perception.

Trailer here