(Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari)

Germany. 1919.

Crew

Director – Robert Wiene, Screenplay – Hans Janowitz & Carl Mayer, Story – Hans Janowitz, Producer – Erich Pommer, Photography (b&w) – Willy Hameister, Production Design – Walter Reimann, Walter Rohrig & Hermann Warm. Production Company – Decla-Bioscop.

Cast

Werner Krauss (Dr Caligari), Frederich Feher (Francis), Conrad Veidt (Cesare), Lil Dagover (Jane Olsen), Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Criminal), Hans Heinrich von Twardowski (Alan), Rudolf Lettinger (Dr Olsen)

Plot

The showman Caligari appears in the town of Holwenstall with his marvel Cesare the Somnambulist, a man who has been asleep for 23 years and is now under Caligari’s hypnotic control. Caligari claims that Cesare can predict the future. The arrogant young Alan rises to accept the challenge and asks how long he will live to which Cesare replies “Until dawn.” That night Alan is murdered. Cesare becomes infatuated with Jane, the daughter of the town’s doctor, and kidnaps her but is hunted down by the townspeople. Jane’s fiance Francis follows Dr Caligari and discovers his real identity as the head of an insane asylum.

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is one of, if not the, most influential of all silent films. It was a huge artistic success in its time. Its impact on early fantastic cinema is immeasurable, its influence being seen in the likes of the Communist sf film Aelita (1924); other German silents such as The Golem (1920) and Nosferatu (1922) and the films of Fritz Lang such as Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (1922) and Metropolis (1927); and the Universal horrors of the 1930s, especially The Bat Whispers (1930), Frankenstein (1931), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) and Son of Frankenstein (1939).

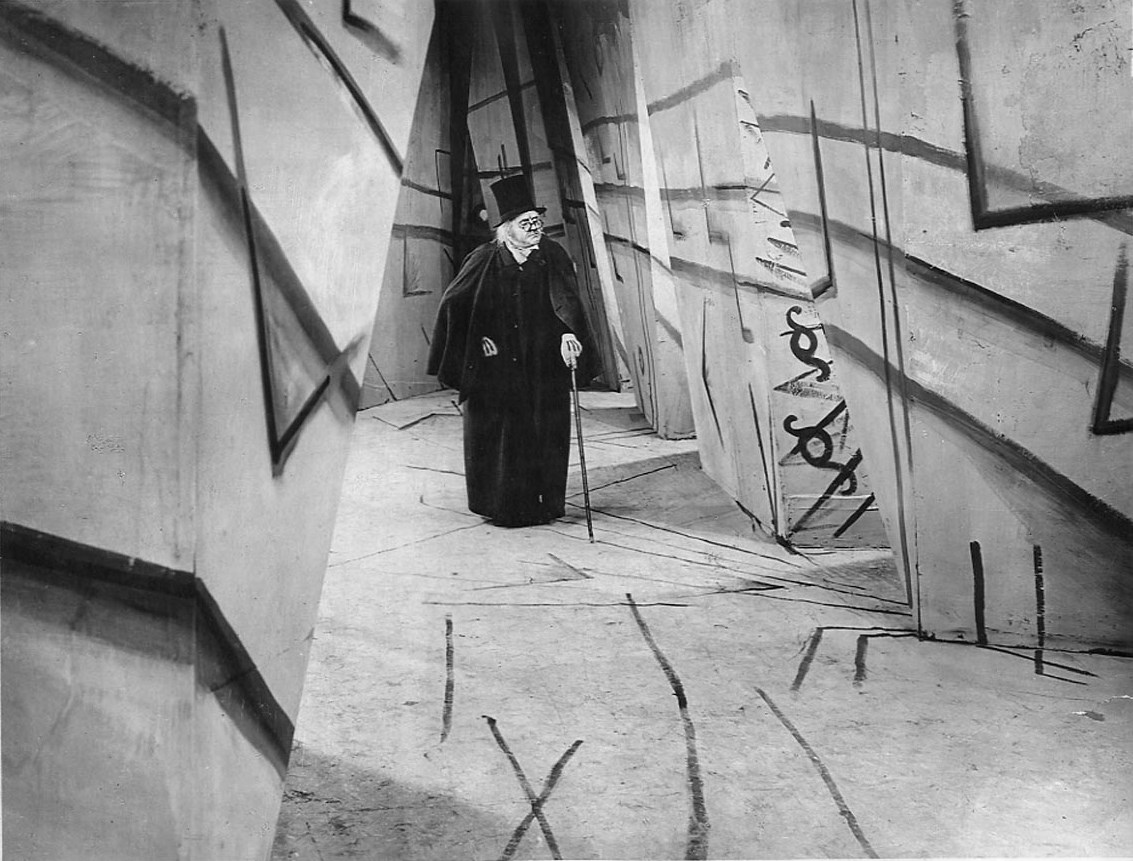

What made the entire world pay attention to The Cabinet of Dr Caligari was its distorted worldview. All the sets are built crooked and misshapen; the backgrounds are jutting angular flats and zigzag perspectives; and the lighting is filled with bloated shadows (which were painted directly onto the sets). As such, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari inspired few direct imitators – and one can see why, it was such a bewildering take on everything that had gone before. Most importantly, in terms of its influence on the German silents and Hollywood’s Golden Age, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari taught that architecture could stand for mood. Hollywood of the 1930s would tie this directly to a Gothic view of a world filled with science-unleashed monsters.

Following Siegfried Kracauer’s influential analysis of the film in From Caligari To Hitler: A Psychological History Of The German Film (1947), there has been the tendency to read The Cabinet of Dr Caligari in terms of Nazism – with Caligari the hypnotist standing in for Hitler the demagogue and Cesare for the German masses. This is perhaps too obvious and too clumsy – Hitler after all did not come into power for another decade after The Cabinet of Dr Caligari came out and it is difficult to see how a film can reflect events that have not yet happened.

More subtly though, the film seems to resonate with the distorted worldview that echoed around the world after the Great War 1914-18. There was the feeling that the Great War had deeply scarred the world, that it had thrown things forever amok and the world could no longer be understood rationally. (The 1920s was also the decade where major artistic movements such as Surrealism, Symbolism and Cubism also came to the fore, representing a fractured depiction of the world that radically departed from objective depiction).

Hans Janowitz and Robert Wiene were inspired by a real-life murder and their intent was to show a distorted world on screen. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari was the first film in cinema to offer a subjective depiction of events on screen – ie. what was seen on screen was not real, it was not a documentary-like depiction of reality, it was a subjective simulation of it. Here though, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari‘s vision ended up being diluted by producer Erich Pommer who was responsible for the insertion of a framing wraparound that showed everything that had happened as being the delusions of someone in an asylum, one where Caligari is the head doctor and the other characters are patients. It is a framework that waters down the impact of the original vision – instead of being a worldview that a viewer is forced to adjust to, it is one that is now explained away with the safety net of only being a madman’s delusion, not unakin to the old “It was all a dream” ending.

Today, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari seems dated and stagy, even occasionally laughable. There is never any sense of place to any of the jutting, angular, shadowy settings – there is nothing that differentiates say the police station from the streets, or a hillside from a boudoir – the effect is more like actors playing on a single stage set. Also working against it is the hammy acting, particularly of Werner Krauss as Caligari and Lil Dagover who badly overdoes the weeping Gothic willow role.

That is not to say that the film does not exert its own creepy influence. The moment Alan cockily asks Cesare how long he will live, only to be answered “Until dawn,” is one of those classic moments of horror – and one that seems all the more chilling for its being relayed by a title card rather than sound. Conrad Veidt’s mime work, staggering through the darkened bloated alleyways in a peculiar spidery, skeletal gait has an unsettling effect too.

There have been four nominal remakes – The Cabinet of Caligari (1962), a psycho-thriller written by Robert Bloch, which appropriates occasional moments of Caligarian imagery in an old dark house story; Dr. Caligari (1989), a surreal arthouse effort from director Stephen Sayadian; the short film Dead By Dawn (2004); and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (2005), which attempted a direct shot-for-shot remake in sound. Numerous films have conducted homage to Caligari and its stylised mood – Aelita (1924), The Fall of the House of Usher (1928), House of Dracula (1945), Dorian Grey as Reflected in the Yellow Press (1984), Dreamscape (1984), Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice (1988) and The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Cabinet of Dr Ramirez (1991), Guy Maddin’s Careful (1992) and Twilight of the Ice Nymphs (1997), Tobe Hooper’s The Apartment Complex (1999) and Queen of the Damned (2002).

The director was originally to have been Fritz Lang who went on to make the crime film The Spiders (1919) instead and the role went to Robert Wiene. Wiene would make several other horror films during the 1920s, including Genuine (1920) about a femme fatale, which appropriates the same style of exaggerated lighting effects an distorted sets as Caligari, and the original version of The Hands of Orlac (1924) about a pianist whose hand transplants start to develop their own life. He made sixty films between the 1910s and his last directorial work in 1934. After this period, he fled Germany with the rise of the Nazis and went to live in France and died there in 1938. Conrad Veidt emigrated to the US during the late 1930s where he maintained a career in movies, most famously in The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and Casablanca (1942).

Trailer here

Full film available here:-