aka The Horror of Dracula

UK. 1958.

Crew

Director – Terence Fisher, Screenplay – Jimmy Sangster, Based on the Novel Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker, Producer – Anthony Hinds, Photography – Jack Asher, Music – James Bernard, Special Effects – Syd Pearson, Makeup – Phil Leaky, Art Direction – Bernard Robinson. Production Company – Hammer

Cast

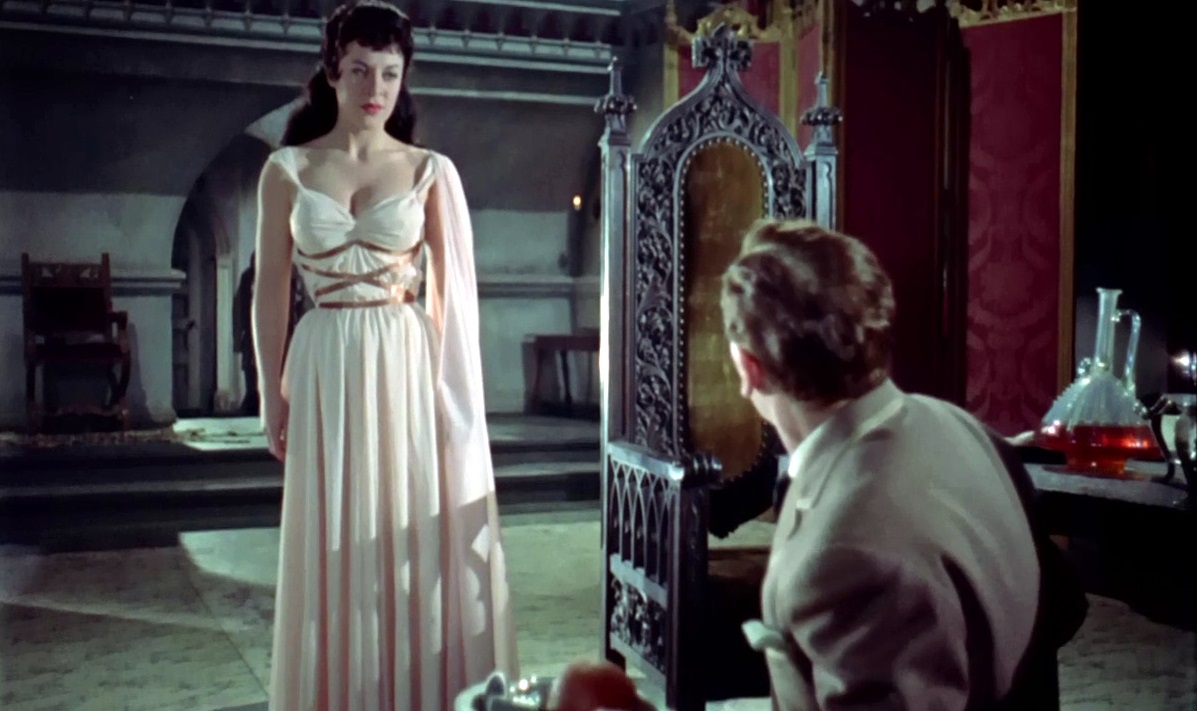

Peter Cushing (Dr Van Helsing), Christopher Lee (Count Dracula), Michael Gough (Arthur Holmwood), John Van Eyssen (Jonathan Harker), Melissa Stribling (Mina Holmwood), Carol Marsh (Lucy Holmwood), Valerie Gaunt (Vampire Woman)

Plot

Posing as a librarian, vampire hunter Jonathan Harker travels to Castle Dracula where he is welcomed by the courtly Count Dracula. Harker attempts to kill Dracula and eliminate the vampire menace that Dracula spreads but the sun sets before he can do so. Jonathan’s body and diary are found by his friend Dr Van Helsing who stakes him and takes the sad news on to his e Lucy Holmwood. There Van Helsing finds that Lucy has become Dracula’s prey. Joined by her brother Arthur, Van Helsing begins a search for Dracula, to stake and kill him before Lucy is fully claimed as a vampire.

Dracula – usually better known under its American retitling, The Horror of Dracula – is the cornerstone of the Hammer Films legend. Although The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) the year before was beginning of Hammer’s success, The Horror of Dracula was the one that set Hammer on the map and marked the beginning of Hammer’s domination over the horror scene for the next fifteen years. (For more detail see The Anglo-Horror Cycle). The Horror of Dracula‘s status, certainly in Anglo-horror fandom, is sacrosanct and its importance near mythic. The essence of what the Hammer film was all about is here – the darkly magnetic presence and aristocratic haughtiness of Christopher Lee; the commanding, straight-arrow rationalism of Peter Cushing; the florid shock hand of director Terence Fisher; the essential British repressions of sexuality and convention that Anglo-horror would pierce a stake right through; and the laughably dated shocked critical outcry.

Where then to view The Horror of Dracula today? Hammer films, particularly the early ones, have not dated well. Today their pace seems slow; the shocks that caused such a critical outcry (and then quickly transformed into the expected mainstay of this particular genre) seem absurdly mannered, even laughable. The rich and floridly colourful sets seem flat and stagebound and James Bernard’s celebrated scores loud and unsubtle. Yet The Horror of Dracula holds undeniable effect.

One must understand exactly what it represented to audiences back then. To an audience raised on the Bela Lugosi Dracula (1931) and the cardboard, melodramatic figure that Dracula became among the Universal monsters line-up in the 1940s, The Horror of Dracula must have had an incredible shock value. For one, it was in colour – which meant that one could see the blood in its rich, overripe scarlet detail – and that alone made it an immediately different film to the Bela Lugosi version. For another, it was not as stagebound as the Lugosi version – Terence Fisher’s camera is kinetic and alive, always on the move.

As an attempt at adapting Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), The Horror of Dracula is never any better or worse than any other version. Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster liberally sacrifices parts here and there for the economy of plot and budget – out go Renfield and the asylum (although these later appeared in Hammer’s Dracula – Prince of Darkness [1966]). Gone too is the magnificently ambient opening journey to Castle Dracula, the pursuit climax and set-pieces like the crashing of the Demeter. Gone too is Dracula as a supernatural being – “It is a common fallacy,” says Van Helsing, “that vampires can change into bats and wolves,” which conveniently does away with having to create costly effects sequences. (Although said fallacy seemed to have been disproven by the time of later sequels). Despite the liberties he takes with Bram Stoker, Jimmy Sangster nevertheless preserves the essence of the book.

(One of the irksome parts of film is its geographic hodgepodge – Dracula’s castle is located near Klausenberg (Cluj) in Rumania, which is near Transylvania. Yet according to the film, Rumania is supposed to border a country that contains both Karlstat (a town in Sweden) and Inglostadt (a town in Germany). In the real world, Germany and Rumania are separated by at least Hungary and either Austria or Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic; while Rumania and Sweden are separated by the Baltic Sea and either Russia or Poland).

The remarkable sexual element present in the Bram Stoker book (wherein Dracula essentially became a sexual predator, plundering the prim, virginal heroines and turning them into sexually aggressive and irresistible creatures), which was only fleetingly touched on in the Lugosi Dracula, is clearly brought out here – Mina sits up in bed in a V-neck nightgown that does a remarkable job of holding in more than one would ever think possible with her window open waiting for Dracula, and at other points the women invitingly tilt their necks up in anticipation. “It is established victims consciously resent being dominated by vampirism but are unable to resist the practice,” Van Helsing states. The Bela Lugosi version bled the film and its women dry of any sexual vitality but here Dracula had well and truly emerged from the Victorian closet. Part of the shock value that The Horror of Dracula had was its very wantonness in this regard.

In person, Dracula was 6’5″ Christopher Lee. Christopher Lee incarnated Dracula as a haughty, imposing nobleman (in real life Lee traces his ancestry back to the Emperor Charlemagne). Bela Lugosi was a puffed-up ham, all stuffed-shirt menace; Christopher Lee, going back to the Stoker book, is introduced as a perfect gentleman who with shock rapidity turns into a ravening animal. When this Dracula is enraged, he is an animal, hissing, his eyes turning scarlet red. Not even Bram Stoker managed to show Dracula with this kind of raw lasciviousness. On the side of good was Peter Cushing who makes the definitive Van Helsing. Thankfully gone is the Dutch accent that Stoker gave Van Helsing and Peter Cushing is able to bring his customary genteel and commanding authority to the role. There is no greater sense in cinematic vampire mythology of Van Helsing as a man of reason who sits astride both science and religion with equal ease, holding society safe against primal forces than there is in Peter Cushing’s performance.

Most of all, The Horror of Dracula belongs to Terence Fisher who subsequently became Hammer’s most prominent director and developed a considerable critical cult within genre fandom. Fisher has no time for Bram Stoker’s Romantic imagery (or even subtlety) and heads straight for shock effect with all guns blazing. There is a shock scene where Valerie Gaunt tries to sink her teeth into Jonathan’s neck as he comforts her, only to be interrupted as Christopher Lee bursts in through a door – in this moment, Terence Fisher shock-cuts to a closeup of Lee’s face, eyes wide-open, blazing blood red and two trails of blood dripping from his fangs, and then has him leap across a table to throw both of them aside.

The climax offers a stunning battle between the forces of light and darkness and is an indelible image in horror film – Van Helsing pursues Dracula into the library and leaps across a table to rip the curtains open, exposing an area of sunlight, then jumps on a table and grabs two candelabra to form a cross, which he uses to drive Dracula into the beam of sunlight, causing him to crumble into dust that is then blown away by a mysterious gust of wind as the end credits roll. It is a set-piece that even outstrips the climax in the book.

Hammer’s other Dracula films are:– The Brides of Dracula (1960), Dracula – Prince of Darkness (1966), Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968), Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), Scars of Dracula (1971), Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972), The Satanic Rites of Dracula/Count Dracula and His Vampire Bride (1973) and The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires/The Seven Brothers Meet Dracula (1974). Christopher Lee appears in all except Brides of Dracula and Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires. Peter Cushing plays Van Helsing again in Brides of Dracula, Dracula A.D. 1972, Satanic Rites of Dracula and Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires. Countess Dracula (1971) is a Hammer film but not a Dracula film and in fact tells the legend of Countess Elizabeth Bathory. The Horror of Dracula was later uncreditedly remade, often copying scenes direct, with the Pakistani Dracula in Pakistan (1967). Lee also played Dracula in a further remake of the Bram Stoker novel Count Dracula (1970), a tatty production from eploitation director Jess Franco; in the documentary In Search of Dracula (1975) in which he not only narrates but plays both Dracula and Vlad the Impaler in recreation scenes; and in the French comedy Dracula, Father and Son (1976) where he plays a Dracula who gets mistaken for Christopher Lee and then cast in a British horror film playing Dracula.

Other adaptations of Dracula are:– the silent classic Nosferatu (1922); the classic Bela Lugosi version Dracula (1931); the Spanish language version Dracula (1931) shot on the same sets as the Lugosi version starring Carlos Villarias; Count Dracula (1970) a continental production that also featured Christopher Lee; Dracula (1974), a tv movie starring Jack Palance; Count Dracula (1977), a BBC tv mini-series featuring Louis Jourdan; Dracula (1979), a lush remake starring Frank Langella; Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) with Klaus Kinski; Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), featuring Gary Oldman; the Italian-German modernised adaptation Dracula (2002) starring Patrick Bergin; Guy Maddin’s silent ballet adaptation Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002); Dracula (2006), the BBC tv adaptation starring Marc Warren; the low-budget modernised Dracula (2009); Dario Argento’s Dracula (2012) with Thomas Kretschmann as Dracula; the low-budget Canadian Terror of Dracula (2012) with director Anthony D.P. Mann as Dracula; the tv series Dracula (2013-4) with Jonathan Rhys Meyers; the BBC mini-series Dracula (2020) starring Claes Bang; Bram Stoker’s Van Helsing (2021), which actually features no Dracula; The Asylum’s Dracula: The Original Living Vampire (2022) with Jake Herbert, which actually features no Dracula; the remake of Nosferatu (2024) with Bill Skarsgård; and Luc Besson’s Dracula: A Love Tale (2025).

Terence Fisher’s other genre films are:– the sf films Four Sided Triangle (1953) and Spaceways (1953), The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959), The Mummy (1959), The Stranglers of Bombay (1959), The Brides of Dracula (1960), The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll (1960), The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), The Phantom of the Opera (1962), The Gorgon (1964), Dracula – Prince of Darkness (1966), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), The Devil Rides Out/The Devil’s Bride (1968), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974), all for Hammer. Outside of Hammer, Fisher has made the Old Dark House comedy The Horror of It All (1964) and the alien invasion films The Earth Dies Screaming (1964), Island of Terror (1966) and Night of the Big Heat (1967).

Jimmy Sangster’s other genre scripts are:– X the Unknown (1956), The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959), The Mummy (1959), The Brides of Dracula (1960), the psycho-thrillers A Taste of Fear/Scream of Fear (1961), Paranoiac (1963), Maniac (1963), Nightmare (1964), Hysteria (1965), The Nanny (1965) and Crescendo (1970), and Dracula – Prince of Darkness (1966), all for Hammer. Sangster’s non-Hammer scripts are the medical vampire film Blood of the Vampire (1958), the alien invasion film The Trollenberg Terror/The Crawling Eye (1958), Jack the Ripper (1959), the Grand Guignol psycho-thriller Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? (1972), the tv movie psycho-thrillers A Taste of Evil (1971) and Scream Pretty Peggy (1973), the occult tv movie Good Against Evil (1977), the occult film The Legacy (1979), the spy tv movies Billion Dollar Threat (1979) and Once Upon a Spy (1980), the psycho-thriller Phobia (1980) and the story for Disney’s The Devil and Max Devlin (1981). As director, Sangster made three films:– The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), the lesbian vampire film Lust for a Vampire (1971) and the psycho-thriller Fear in the Night (1972), all at Hammer..

Trailer here