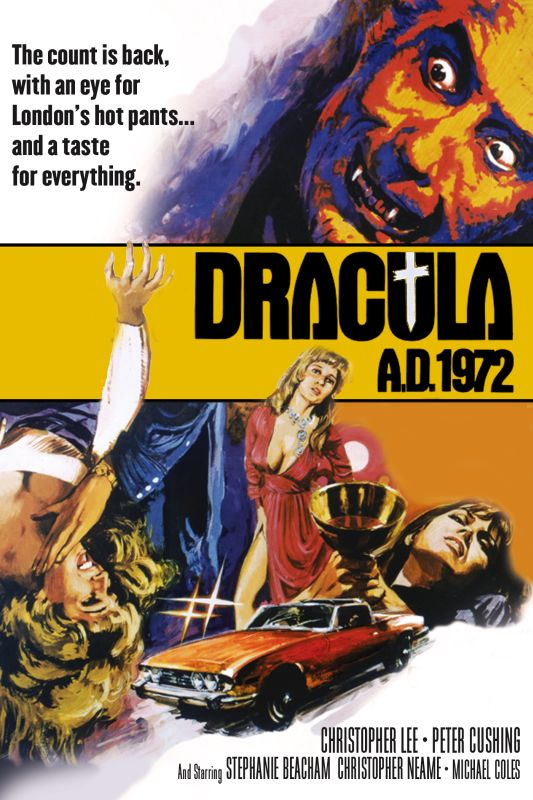

UK. 1972.

Crew

Director – Alan Gibson, Screenplay – Don Houghton, Producer – Josephine Douglas, Photography – Dick Bush, Music – Michael Vickers, Songs – Stoneground, Special Effects – Les Bowie, Makeup – Jill Carpenter, Production Design – Don Mingaye. Production Company – Hammer Films.

Cast

Peter Cushing (Professor Lorrimer Van Helsing/Lawrence Van Helsing), Christopher Lee (Count Dracula), Stephanie Beacham (Jessica Van Helsing), Christopher Neame (Johnny Alucard), Michael Coles (Inspector Murray), Philip Miller (Bob Tarrant), Marsha Hunt (Gaynor Keating), David Andrews (Detective Sergeant), Caroline Munro (Laura Bellows), Janet Key (Anna Bryant), Michael Kitchen (Greg Puller)

Plot

In 1872, Count Dracula is killed in a confrontation with Lawrence Van Helsing on the outskirts of London. One hundred years later, Johnny Alucard, a descendant of one of Dracula’s disciples, gathers a group of youths to perform a black magic ceremony in the abandoned, deconsecrated St Bartholomew’s church. There he conducts a human sacrifice that restores Dracula to life. One of the youths present at the ceremony is Jessica Van Helsing, granddaughter of Lorrimer Van Helsing, the current descendant of Dracula’s old nemesis. Dracula confers vampire powers on Alucard, allowing him to turn various among the circle of friends into acolytes. As Lorrimer is drawn into the fight by the police investigation, Alucard is determined to bring Jessica to Dracula as a sacrifice so he can take his revenge on the Van Helsing family.

Thanks in large part to Hammer’s own efforts beginning with the groundbreaking Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958), vampire films were making a big comeback in the late 1960s and early 70s. Hammer had themselves spun out six Dracula films by the point of Dracula A.D. 1972 (see bottom of the page for these), as well as various distaff cousins such as Countess Dracula (1971) and the softcore Karnstein series begun with The Vampire Lovers (1970).

Elsewhere, the vampire was emerging in strong flight, although the crisis the genre was facing was how to modernise the vampire. The image of the caped and dinner-suited Bela Lugosi-type vampire seemed an increasingly outmoded figure in modern surroundings. Initial efforts like tv’s Dark Shadows (1966-70) avoided the issue altogether by setting its vampire in a Gothic world that seemed an isolated pocket of the past living in the modern day, while other efforts such as Hammer’s Karnstein series and Andy Warhol’s Dracula (1973) simply added modern sex and gore in period surroundings.

More successful were the likes of Guess What Happened to Count Dracula? (1971), Count Yorga, Vampire (1970), The Velvet Vampire (1971), Blacula (1972), The Night Stalker (1972) and Salem’s Lot (1979), which uprooted the traditional vampire image, cape and all, and transplanted it into modern day surrounds. However, the fight for a modern-day traditional vampire was starting to seem like a losing battle. After George Romero’s remarkable deconstruction Martin (1976), the classic vampire was never the same again and by the time of Love at First Bite (1979) the concept of the dinner-suited vampire in the modern day was openly recognised as anachronistic and played for laughs.

After the unexpected success of Count Yorga, it was no surprise that Hammer’s next Dracula entry followed suit and brought Christopher Lee’s Dracula into the modern-day too. It may well have been an act of creative novelty – the Hammer Draculas were starting to seem stale and most of the sequels could never find much to have Christopher Lee do once they revived him.

Dracula A.D. 1972 looked promising. It boasted the return to the series of Peter Cushing who had not played Van Helsing for twelve years since The Brides of Dracula (1960). The film starts to deal with a modern-day Dracula in encouraging ways – the transition being cleverly signalled by the camera panning from a 19th Century funeral service up into the sky as a jet plane passes overhead.

Despite the intriguing possibilities of seeing Christopher Lee preying on the modern day, Dracula A.D. 1972 proves a major disappointment. Whereas the Count Yorga films and Love at First Bite poked gentle amusement at the idea of a traditional be-caped vampire in the modern world and later efforts such as Salem’s Lot, The Hunger (1983), Fright Night (1985) and Near Dark (1987) made a strong and confidant attempt to show us vampires having adjusted to the modern world, Dracula A.D. 1972 avoids any of its conceptual promise whatsoever and keeps Dracula within the confines of a Gothic church for the entire running time.

The film is half over before it gets Christopher Lee resurrected, while the script only gives him a single line during the first hour. Indeed, the film seems more interested in the petty deviltry of acolyte Christopher Neame, B plot scenes of the youths running around/making out and Peter Cushing trying to warn the investigating police what they are dealing with than giving Dracula anything to do. (Mindedly, you could argue that this is not too different than what Bram Stoker did with Dracula in Dracula (1897) where he made a strong appearance at the start and then remained off-stage for the rest of the book).

There was also the increasing in-roads being made by the youth movement at the time. Since around 1970, Hammer started making concessions to this by casting younger leads and overturning the conservatism that underlay many of their films in favour of open sexuality. The opening scenes where hippies have taken over a posh London party is fascinating to watch a few decades later – we get Stephanie Beacham who appeared in a number of early Anglo-horror films before finding fame as a US soap opera queen in the 1980s, and Caroline Munro – an actress with a long line of genre credits in films such as Hammer’s Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter (1972), The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) and Star Crash (1978) – as dancing Flower Children, an unrecognisable Michael Kitchen of numerous British tv arts programs, and Christopher Neame, another B movie actor subsequently, who looks decidedly raffish in ruffled shirt, velvet coat and rakishly titled fedora. Mindedly, the scene also features the rock group Stoneground, who no-one except perhaps the most obscure vinyl collectors has ever heard of since, which represents the dangers of the appeal to a passing trend of the moment.

On the other hand, the incorporation of the Swinging London youth movement into the Hammer Dracula milieu borders on the laughable: “Dig the music, kids,” says Christopher Neame during the black magic ceremony in one particularly cringeworthy line. [Here Dracula’s resurrection is tied to a Satanic ceremony – something that had never been part of the other Dracula films and sees Hammer also trying to jump aboard the fad for occult films following the huge success of Rosemary’s Baby (1968)]. It was an attempt to appeal to the Swinging 60s London youth movement made by people that weren’t a part of it and feels badly like old school Hammer trying to play catch up and jump aboard a trend that they missed the boat with.

There was a point when Hammer Films represented a challenge to the staidness of the British establishment – when the initial films came out they brought in sexuality and blood, causing a shock and a stir. Now ironically, the studio looks like the old guard trying to get a grasp on the runaway youth movement and realising they don’t have a clue. Peter Cushing, the vanguard of the studio’s outrage as the ruthlessly amoral Baron Frankenstein, is sadly reduced to shaking his head and dispensing grandfatherly concerns that his granddaughter behave in a chaste manner and not hang out with the wrong crowd.

There are minor positive aspects. There is a good opening confrontation with Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing fighting aboard a coach as it crashes, whereupon Dracula falls and is killed by being impaled upon the shattered spokes of a broken cartwheel. It is a sequence that you could easily imagine as the climax of one of Terence Fisher’s florid Dracula entries, which specialised in setting up spectacular dispatches for Dracula, even if Alan Gibson never quite brings it to the type of enthralling brio that you feel that Fisher would have. There is also a moderately exciting scene where Peter Cushing drives Christopher Neame into the bathroom using a mirror to reflect the sunlight in his apartment whereupon Neame falls and turns on the shower and is killed by the running water. Mindedly, in both of these scenes, the vampire is only killed accidentally, something that you feel like Fisher would never have allowed to happen.

On the other hand, Christopher Lee probably has the least to do of any of his Dracula airings, although Peter Cushing comes out suitably distinguished. Crucially though, both of the actors are now starting to look old. A young Stephanie Beachem proves an energetic addition to the canon.

The American version of Dracula A.D. 1972 contains a three-minute sequence at the opening by Donald Glut inviting audiences to join the Dracula Society.

Hammer’s other Dracula films are:– Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958), The Brides of Dracula (1960), Dracula – Prince of Darkness (1966), Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968), Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), Scars of Dracula (1971), The Satanic Rites of Dracula/Count Dracula and His Vampire Bride (1973) and The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires/The Seven Brothers Meet Dracula (1974).

Alan Gibson was a Canadian-born director who had been working in British television during the 1960s. Hammer gave him the reins of the psycho-thriller Crescendo (1970) and then turned the Dracula series over to him with Dracula A.D. 1972 and the subsequent The Satanic Rites of Dracula, which are almost always the poorest regarded entries in the series. Gibson returned to directing British television after that – the only other work he did with Hammer was directing two episodes of their tv series Hammer’s House of Horrors (1980).

Trailer here