Crew

Director – Joel Schumacher, Screenplay – Ebbe Roe Smith, Producers – Timothy Harris, Arnold Kopelson & Herschel Weingrod, Photography – Andrzej Bartkowiak, Music – James Newton Howard, Special Effects Supervisor – Matt Sweeney, Production Design – Berbara Ling. Production Company – Warner Brothers/Le Studio Canal +/Regency Enterprises/Alcor Films

Cast

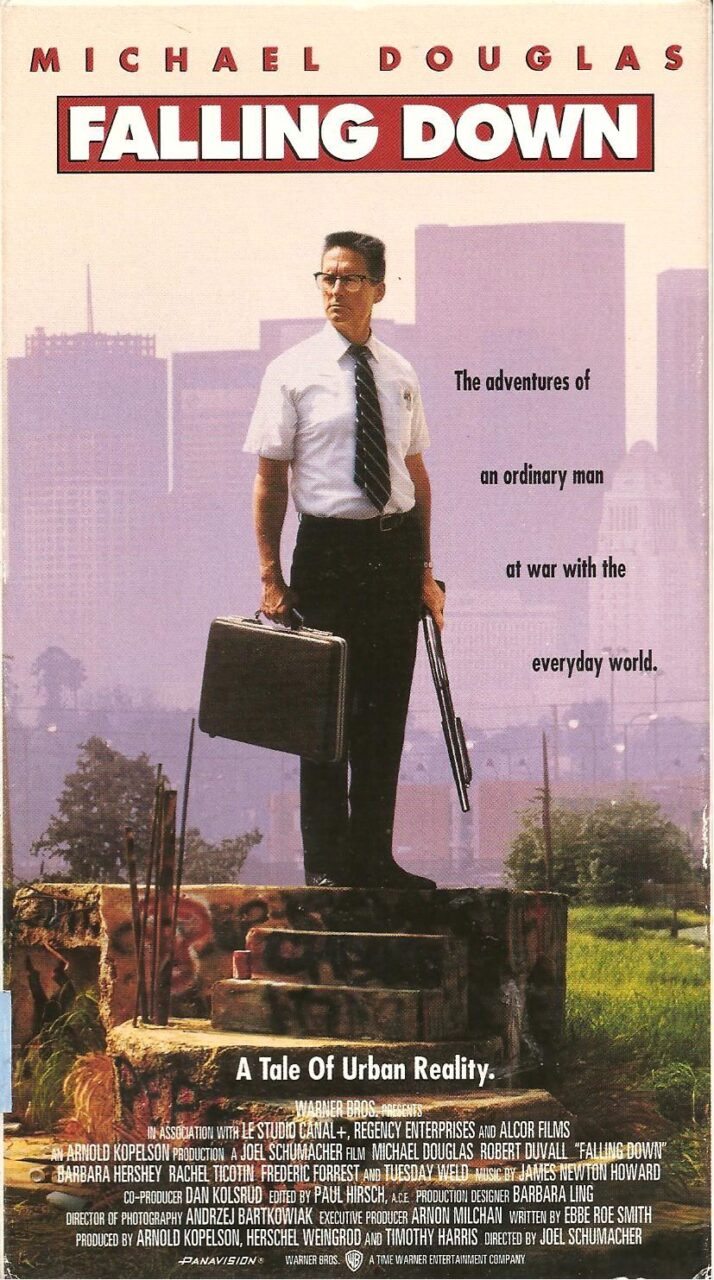

Michael Douglas (Bill Foster), Robert Duvall (Martin Prendergast), Barbara Hershey (Elizabeth Tevino), Rachel Ticotin (Sandra Torres), Tuesday Weld (Amanda Prendergast), Raymond J. Barry (Captain Yardley), Frederic Forrest (Nick), Donald Moffet (Detective Lydecker), Michael Paul Chan (Lee)

Plot

On his way to work, Bill Foster gets stuck in a traffic jam so decides to abandon his car and walk home. However, when a Korean convenience store owner overcharges him for a can of Coke, the mild-mannered Foster erupts into violence. Picking up a bag of assault weapons dropped in a drive-by shooting, Foster walks across the city violently venting his frustrations with the petty rule-makers and the lazily self-interested who make his life a misery.

This slickly mounted A-budget studio film is one of the most offensive films to have come one’s way in some time. When Falling Down came out, it attracted a huge backlash from various minority groups, particularly and understandably from Asian-American communities, and was decried everywhere as an irresponsible pandering to the redneck element of audiences. Unless one is a part of said redneck element, then Falling Down is an unsavoury film.

Falling Down‘s premise of the central character acting out a revenge fantasy against the petty bureaucrats and rule-keepers of modern life is not so offensive in itself, indeed could well have been the grounds for an amusing comedy. (A later and much better psycho-thriller treatment of essentially the same story was Under Pressure [1997]). However, Falling Down does not keep its focus there, it widens its scope to take pot shots at minority groups and blames them as responsible for the central character’s perceived injustices. For example, when Michael Douglas gets violent with the Korean shop-keeper and an Hispanic youth-gang, a large thrust of his rant is because they do not speak English properly, while his smashing up of the Korean’s convenience store is accompanied by him raving about how he is proud to be an American. The poor and unemployed are caricatured as people who are on the scam and lazy – Michael Douglas’s response is to yell at them “Get a job”.

Falling Down is even happy to turn the shooting of people or their being made to suffer heart-attacks into an object of amusement by justifying their torture as just desserts. Even when Falling Down is not outrightly agreeing with its central character, it is invoking laughter at other people’s gay-bashing and sexism – even nice-guy detective Robert Duvall only finds his self-esteem at the end by standing up to his emotionally manipulative wife and ordering her to have dinner ready by the time he gets home.

Sometimes you get the impression that Falling Down is trying to salvage itself somewhat – there are several montage scenes of AIDS victims, people with signs offering work in return for food, a Black man protesting about his refusal by an insurance agency and the like – which seem to be trying to place the film in a context against the bleak human cost that the recession of the 1990s was having.

At the end, the film also tries to distance itself from the point-of-view it has upheld throughout by showing Michael Douglas to be a crazy – in one effective moment at the very end, the film has him turn around, surprised to find that he is suddenly the bad guy. It is a moment that almost works in turning its audience’s sympathies around, however when one looks back and sees the way in which the film has constantly poked fun, derided and invoked sympathy for Michael Douglas’s actions, the point is lost.

Falling Down is not a valid pinpointing of modern urban anxiety; it is plain mean ornery bigotry looking for easy targets to vent its undirected aggression on. In the end, Falling Down‘s only distinction will be an historical one in the same way that something like Red Planet Mars (1952) exerts a fascination today in its ability to sit astride the naked anxieties and bigotry of its time.

Michael Douglas made a string of these politically incorrect films, including also the likes of Fatal Attraction (1987), Basic Instinct (1992) and Disclosure (1994).

Joel Schumacher, who also inflicted Batman & Robin (1997) on the public, is in this author’s opinion the worst director to ever work on an A-budget. Joel Schumacher’s other genre films include The Incredible Shrinking Woman (1981), The Lost Boys (1987), Flatliners (1990), Batman Forever (1995), 8MM (1999), Phone Booth (2002), The Phantom of the Opera (2004), The Number 23 (2007) and Town Creek (2009).