USA. 1931.

Crew

Director – James Whale, Screenplay – Francis Edward Faragogh & Garrett Ford, Adaptation – John L. Balderston, Based on the Play by Peggy Webling of the Novel Frankenstein, or The Modern Promtheus (1818) by Mary W. Shelley, Producer – Carl Laemmle Jr, Photography (b&w) – Arthur Edeson, Visual Effects – John P. Fulton, Mechanical Effects – Frank Grove, Raymond Lindsay & Kenneth Strickfaden, Makeup – Jack Pierce, Art Direction – Charles D. Hall. Production Company – Universal.

Cast

Colin Clive (Henry Frankenstein), Boris Karloff (The Monster), Mae Clarke (Elizabeth), Edward Van Sloan (Dr Waldman), Dwight Frye (Fritz), Frederick Kerr (Baron Frankenstein), John Boles (Victor Moritz)

Plot

Henry Frankenstein is obsessed with creating life. With the aid of his hunchbacked assistant Fritz, he has pieced together a body made up of parts taken from corpses. Together they harness the power of a lightning storm to bring the creation to life. However, the bumbling Fritz has accidentally dropped the genius brain he was sent to obtain for the creature and, unknown to Frankenstein, has substituted an abnormal criminal brain. When the creature comes to life with the abnormal brain in its skull, it then sets about blindly killing people.

1931 is maybe the one year that can be considered the cornerstone of horror cinema. It was this year that produced both the Bela Lugosi Dracula (1931) and this, the Boris Karloff version of Frankenstein. [The same year also produced the Fredric March version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) and, although Dr Jekyll is one of the key horror archetypes along with Dracula and the Frankenstein monster and the 1931 Dr. Jekyll is probably the definitive rendering of the story, this version did not have such a key influence as the other two]. Between them, Dracula and Frankenstein created the so-called Golden Age of Horror, which is generally agreed upon as lasting from 1931 to 1939.

Even more so, they created the two defining archetypes of the horror genre – Bela Lugosi’s caped European-accented vampire and Boris Karloff’s dumb and stumbling, lop-topped, bolt-necked monster. These two horror icons have been endlessly copied, parodied, turned into Halloween costumes and toys, so much so that they now seem the two singular versions of the characters that stick in the public mind, despite numerous revisionist efforts that have been made of either story. While both Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) have been recognised as landmarks of 19th Century Gothic horror, that recognition only emerged subsequent to the film adaptations and it is almost impossible to believe that such stature could not have happened without the way that either character has been endlessly copied and reinterpreted following these two films.

Though this version of Frankenstein is the one that influences all others, there is a vast difference between it and the story that Mary Shelley originally wrote. The film crudens the story to say the least – Shelley wrote a story about an artificial creation arguing with its creator about its cursed condition; the film makes the monster into a dumb brute. Moreover, with the addition of the nonsense about ‘Normal’ and ‘Abnormal’ brains, the film cuts all the philosophical debate of the book in one foul swoop and takes the story from the realm of moral outrage to make it merely a biological problem upon the monster’s part. Underlying the talk about Abnormal brains is the type of foolish phrenological thinking that was discredited as long ago as the 19th Century. [Phrenology was the proto-psychological science that believed personality was determined by the shape of one’s skull].

Frankenstein was not the first but certainly was the most influential film on the mad scientist genre. The notions of science that run through the film and others of its ilk are intriguing. One must remember that at the time that Frankenstein and the mad scientist films that followed were made the famous Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925, where laws that forbade the teaching of evolution in classrooms were tried in an American court, was less than a decade old. Science was still seen by most of the American public as a dangerous philosophy rather than as a rational discipline. Again and again in these mad scientist films the same basic theme is played out – science is seen as defying divine provenance (mad scientists were constantly defying taboo areas as far as the religionists were concerned – attempting to prolong youth, raising the dead, playing around with the relationship between human and ape), invariably the experiment would go out of control, creating a monster that would rampage about, causing much social devastation before being brought down. Notedly in these films, the monsters would rarely be destroyed by the forces of law and order – ie. the police, the military – but by a lynch mob of concerned citizens. As the scientist and creation were brought down, someone would comment something along the lines of: “There are some things man was better not to know” – a line that first appeared in the Karloff-Lugosi The Invisible Ray (1936).

This is the way horror of the 1930s and 40s regarded science – as something dangerous that could overturn the fragile balance of society and that the world was better off not knowing about these things. If science-fiction is about the way that we confront new ideas and possibilities, then mad science cinema is, as Alexei and Cory Panshin commented of the original Frankenstein novel, “like someone lighting a fire and then running away cowering at what they have unleashed.” This version of Frankenstein feels it is taking place in an insane fevre dream of the imagination. It is directly seen that to achieve the kind of ideas he needs to succeed that Colin Clive’s Frankenstein needs not employ calm methodology and double blind experiments, but to create in a fevered delirium. Ominous warnings are delivered: “Your health will be ruined if you persist with this madness. You have created a monster and it will destroy you.” Eventually Frankenstein collapses in exhaustion – the kind of madness that falls into the 19th Century notion of mental illness as something that causes the body to completely collapse around it.

Like the Bela Lugosi Dracula, Frankenstein is adapted not from the original source novel but comes filtered through a play adaptation written by Peggy Webling that first appeared on the London stage in 1927. In fact, the stage origins hang heavily over Frankenstein – in the pre-credits opening, Edward Van Sloan appears from behind a curtain, nodding knowledgeably at the audience to give them warning about the content and telling them they might find it too frightening. The film retains other elements that were introduced in the play, like changing Frankenstein’s fist name from Victor to Henry.

Universal recruited the eccentric James Whale as director. Whale had begun as a stage director and his two previous films, Journey’s End (1931) and Waterloo Bridge (1931), were both adapted from stage plays. Whale’s later genre films became known for their droll, eccentric humour, although this is not particularly present in Frankenstein. Nevertheless the atmosphere that Whale creates in Frankenstein is unusual. Whale and the production designers were clearly influenced by The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919) and the stylised German Expressionist silent films of the previous decade. Caligari was revolutionary in that it took place inside the imagination of a madman, which was depicted as filled with twisted, distorted sets and bloated, exaggerated shadows.

Frankenstein takes place in a sort of Mittel-Europe twilit netherworld, one that has been created like an Expressionist stage set filled with clod hill horizons against obvious painted backdrop skies and starkly ornamented Death figures. The sets take the Caligari influence to ludicrous extremes – a cell is built as a narrow wedge-shape and has a stairway rail that abruptly curves all the way up to meet the ceiling with a lunacy that would make one question the rationality of the architects; gigantic beams angularly bisect hallways; and the lab’s foyer is built in a wild array of brick with at least a thirty-foot height of stairs that stand at a 70 degree gradient.

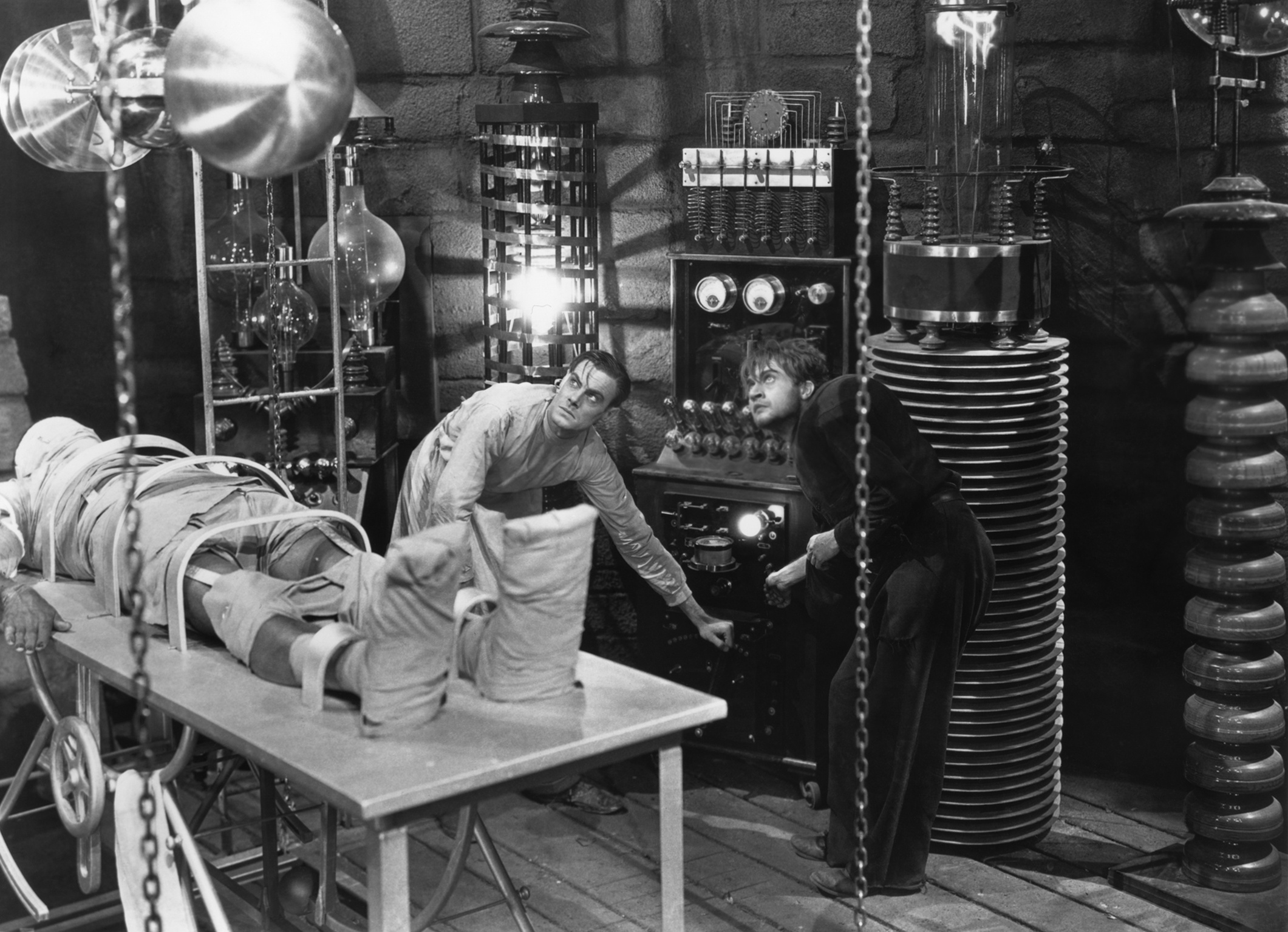

The laboratory is the most impressive of the sets, constructed as an expanding series of concentric circles and filled with some of the most fabulous mad scientist machinery. Frankenstein has a supposedly contemporary setting but the scenery is so loomingly Gothic that the film seems to unintentionally slip into period setting. Even the costumes are thoroughly overdone – Colin Clive wears jodhpurs around the house like it is the most natural thing, while Mae Clarke’s wedding veil is about fifteen feet long.

James Whale directs with wonderfully cold, oblique effect. There is the famous scene of the monster’s entry into the laboratory where we see him for the first time, which is conducted by Whale in a series of three closeups zooming in on Boris Karloff as he backs in and turns into camera. It is a moment of marvellous impact, yet it is also a decidedly theatrical effect coming in the midst of an otherwise placidly directed scene that Whale immediately drops back to again without warning. The film is filled with many such striking effects. The pantomime that Boris Karloff goes through as he reaches up to try and touch the sunlight coming in to the laboratory, clenching his fingers as though to try and hold it, is an image that holds a wonderful primality that needs no accompanying words. Other memorable moments include the scene with the little girl, which has a surprising tenderness. There is no music soundtrack to the film, adding even further to the obliqueness of Whale’s direction.

Boris Karloff gives a fine performance as The Monster. [Interestingly enough in the pre-film credits list (although not the post-film credits), Karloff is only billed as “?”. It would take a good deal for Karloff to actually get his full name on the Frankenstein films – by the time of the sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935), he had become so famous he was only billed as “Karloff”. Frankenstein nevertheless managed to make his name despite this]. For all that is said about the horror film’s ability to corrupt, in years to come the fan mail that Karloff received came from children who felt sympathy for the monster. There is a wonderful sense of innocence to the monster, a dumb hulking brute with the heart of a child. The dumb Big Lug smile that creaks across Karloff’s smile is particularly memorable.

Everybody else goes at their performances with a melodramaticism that suggests they were still back making silent pictures, the most notable offender being Colin Clive, who plays with a theatricality that begins to create a bizarre conviction after a time. The most normal of performances is the amusingly dry, unflappable one from Frederick Kerr as the good Baron.

In 1987, finally restored was the legendary scene where Boris Karloff and the little girl sit tossing flowers into the river and they run out of flowers whereupon he tosses her in. There is something grotesquely funny to the scene and it is perhaps the one place in the film where James Whale’s dark sense of humour makes itself felt. Although in Boris Karloff’s eyes, the scene was a mistake that made the monster’s actions less innocent.

There were a number of sequels to Frankenstein. James Whale returned to make Bride of Frankenstein (1935), with Boris Karloff and Colin Clive repeating their roles, which many consider this to be the finest of the Universal series. Rowland V. Lee stepped in to direct the also worthwhile Son of Frankenstein (1939), which also featured Boris Karloff. Karloff dropped out after that point and was replaced by Lon Chaney Jr for the dreary The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942). Chaney played the monster as a dumb brute with none of Karloff’s sense of pathos and by this point the series started to pass into a clichéd formula where some descendent of Frankenstein would find the monster and revive it with the usually cataclysmic consequences. Universal next began pairing their in-house monsters up against each other starting with Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) featuring Bela Lugosi as the monster, and with Glenn Strange then taking up the role to continue through House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), before the monster arrived at the ultimate indignity of being played for laughs in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). None of the subsequent actors to play the part created any of the sympathy for the monster that Boris Karloff did.

There had been three silent versions of the story made before this, including the famous Thomas Edison produced Frankenstein (1910), the lost Life Without Soul (1915) and the lost Italian The Monster of Frankenstein (1920). There have been several remakes – Hammer’s excellent The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) with Peter Cushing as the Baron and Christopher Lee as the monster, a film that spun out its own series of sequels (see for which); a 1968 Thames tv production with Ian Holm as both the Baron and the monster; Hammer’s unfunny comic remake The Horror of Frankenstein (1970) with Ralph Bates as the Baron and Dave Prowse as the monster; Dan Curtis’s tv movie adaptation Frankenstein (1973) with Robert Foxworth as the Baron and Bo Svenson as the monster; the tv mini-series Frankenstein: The True Story (1974), which returned much more to the book, and featured Leonard Whiting as the Baron and Michael Sarrazin as the monster; the Swedish-Irish production Victor Frankenstein (1977) starring Leon Vitali as the Baron as Per Oscarsson as the monster; the tv movie Frankenstein (1984), with Robert Powell as the Baron and David Warner as the monster; the little-seen tv movie Frankenstein (1986) with Carl Beck as Frankenstein and Chris Sarandon as the monster; David Wickes’s dull tv movie Frankenstein (1992) with Patrick Bergin as the Baron and Randy Quaid as the monster; Kenneth Branagh’s faithful, big-budget Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) with Branagh as the Baron and Robert De Niro as the monster; the Hallmark tv mini-series Frankenstein (2004) with Alec Newman as Frankenstein and Luke Goss as the monster; Danny Boyle’s stage version of Frankenstein (2011) with Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller alternating the role of Frankenstein and creation; the low-budget Frankenstein: Day of the Beast (2011) with Adam Stephenson as Frankenstein and Tim Krueger as the monster; Victor Frankenstein (2015) with James McAvoy as Frankenstein; and Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025) with Oscar Isaac as Frankenstein and Jacob Elordi as the creature.

There have been numerous spinoffs and unauthorised sequels. Here is what is almost certainly not an exhaustive list. Sequels and follow-ups have included:– Frankenstein 1970 (1958), Frankenstein’s Daughter (1958), Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966), Frankenstein Conquers the World (1966), Flick/Frankenstein on Campus (1969), Lady Frankenstein (1971), Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein/Flesh for Frankenstein (1973), Frankenstein’s Castle of Freaks (1974), Frankenstein Island (1981), The Bride (1985), Waxwork II: Lost in Time (1992), Alvin and the Chipmunks Meets Frankenstein (1999), Frankenstein and the Werewolf Reborn (2000), I Frankenstein (2014) and Frankenstein Legacy (2024). Tales of Frankenstein (1958) was the 30-minute pilot for a Frankenstein tv series from Hammer that never emerged. The anime The Empire of Corpses (2015) is set in a Steampunk world where Frankenstein’s experiments have changed the world.

Frankenstein and/or the monster have been paired with various other monsters in Dracula vs Frankenstein (1970), Dracula vs. Frankenstein (1971), Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein (1972), Blood (1974), Howl of the Devil (1987), The Monster Squad (1987), The Creeps/Deformed Monsters (1997), House of Frankenstein (tv mini-series, 1997), the Finnish-made Frankenström (2001), Van Helsing (2004), Frankenstein and the Creature from Blood Cove (2005), Frankenstein vs the Wolfman (2008), House of the Wolf Man (2009), Monster Brawl (2011), Frankenstein vs the Mummy (2015), Monster Mash (2024) and the tv series Penny Dreadful (2014-6), and for comedic effect in the Mexican comedies Castle of the Monsters (1957) and Frankenstein, the Vampire and Co (1961), the children’s puppet film Mad Monster Party? (1967), Son of Dracula (1974), Transylvania 6-5000 (1985), Monster Mash: The Movie (1995), Hotel Transylvania (2012) and its sequels Hotel Transylvania 2 (2015) and Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation (2018).

There have also been numerous parodies – most famously Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein (1974) and The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and others such as Carry On Screaming (1966), the short-lived tv sitcom Struck by Lightning (1979), Frankenstein’s Great Aunt Tillie (1985), Frankenstein General Hospital (1988), Frankenhooker (1990), Frankenstein: The College Years (tv movie, 1991), the short Frankenthumb (2002), Frankenpimp (2009), the The Diary of Anne Frankenstein segment of Chillerama (2011) and Lisa Frankenstein (2024).

Frankenstein ’80 (1972), Dr Franken (tv movie, 1981), Frankenstein 90 (1984), Frankenstein’s Baby (tv movie, 1990), Mr. Stitch (1995), the Dean Koontz Frankenstein (tv movie, 2004), Frankenstein Reborn (2005), Frankenstein’s Bloody Nightmare (2006), Frankenstein (2007), The Frankenstein Syndrome/The Prometheus Project (2010), Closer to God (2014), Frankenstein (2015) and Depraved (2019) were attempts to modernise the story, while The Frankenstein Theory (2013) and Frankenstein’s Army (2013) are Found Footage variations. Frankenstein 2000 (1992) seems to want to offer a modernisation but is in fact a film of slim connection about a slow-witted handyman resurected from the dead with psychic powers. Sexcula (1974), The Erotic Adventures of Frankenstein (1975), Frankenstein – Italian Style (1977), Lust for Frankenstein (1998), Mistress Frankenstein (2000) and Bikini Frankenstein (2010) were adult takes on the story.

Billy Frankenstein (1998) and Bolt Neck/Big Monster on Campus (1999) were children’s movie versions. The monster also makes appearances in films as varied as the nudies House on Bare Mountain (1962) and Kiss Me Quick/Dr Breedlove (1964), the James Bond spoof Casino Royale (1967), the haunting Spanish childhood drama The Spirit of the Beehive (1974), as a nemesis in various of the Mexican wrestling superhero Santo series such as Santo and Blue Demon Meets the Monsters (1969), Santo and Blue Demon vs Dr Frankenstein (1970), Santo vs Frankenstein’s Daughter (1972) and Invasion of the Dead (1972), and had his visage used as the patriarch in tv’s The Munsters (1964-6). Other variants include the teenage version I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957); the cartoon series’ Frankenstein Jr and the Impossibles (1966-8) and Monster Squad (1976-7); a Blaxploitation version Blackenstein (1973); Tim Burton’s stylised children’s movie homage, the short Frankenweenie (1985), later expanded as the stop-motion animated Frankenweenie (2012); Frankenstein and Me (1996), a delightful children’s film about a love of monster movies where a kid tries to resurrect the monster; Frankenstein Unlimited (2009), an anthology of Frankenstein themed short films; and Army of Frankensteins (2014) in which a replicated army of Frankenstein monsters time travel back to fight in the American Civil War.

There have been several films about the events of the writing of the Frankenstein novel, including Gothic (1986), Haunted Summer (1988), Rowing with the Wind (1988), A Nightmare Wakes (2020) and the biopic Mary Shelley (2017), even Frankenstein Unbound (1990), which has a time-traveller meeting both Mary Shelley and Frankenstein and monster, and the tv series The Frankenstein Chronicles (2015-7), which winds Mary Shelley in as a character and features a police investigation into somebody conducting a series of Frankenstein-like experiments. Frankenstein: A Modern Myth (2012) is a documentary about the enduring popularity of the Frankenstein myth.

Despite the title, Frankenstein Meets the Spacemonster (1965) is a science-fiction film about an android and alien invaders that does not feature anything to do with Frankenstein or his monster; while Frankenstein’s Bloody Terror (1968) is not a Frankenstein film but is about a werewolf who is supposedly an ancestor of the Frankenstein family; and the gonzo Japanese gore film Vampire Girl vs Frankenstein Girl (2009) features a girl resurrected from the dead but no Dr Frankenstein.

Director James Whale went onto make a number of other classic horror films. These included the dark comedy The Old Dark House (1932), The Invisible Man (1933) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Also of note is Gods and Monsters (1998), a biopic about Whale’s homosexuality and never completely explained death by drowning in 1957.

Trailer here