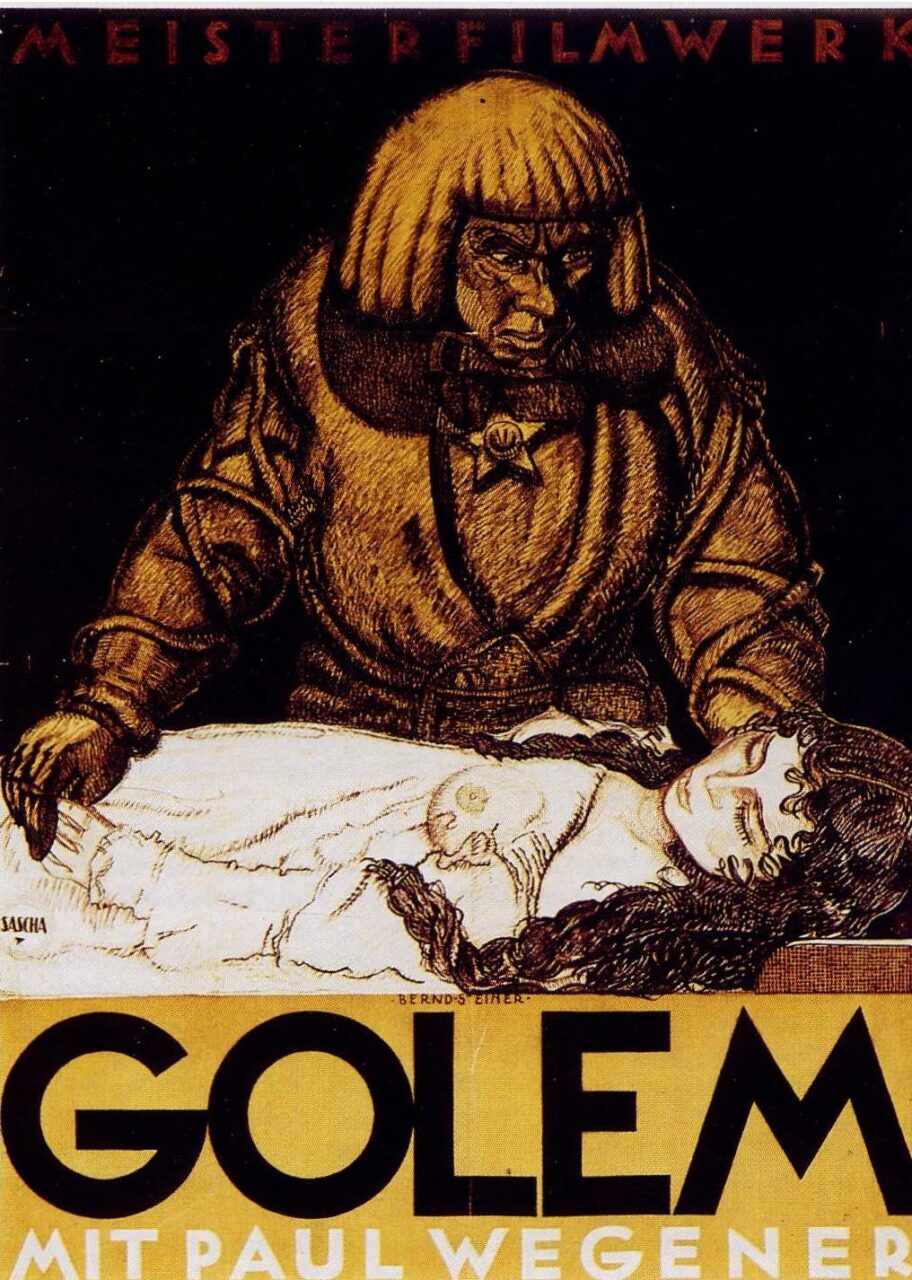

(Der Golem, Wie er in die Welt Kam)

Germany. 1920.

Crew

Directors – Carl Boese & Paul Wegener, Supervising Director – Ernst Lubitsch, Screenplay – Paul Wegener & Henrik Galeen, Photography (b&w) – Karl Freund & Guido Seeber, Production Design – Hans Poelzig. Production Company – Projections-AG Union/UFA.

Cast

Albert Steinruck (Rabbi Loew), Paul Wegener (The Golem), Lyda Salmanova (Miriam Loew), Lothar Muthel (Knight Florian), Ernst Deutsch (Famulus), Otto Gebuhr (Emperor)

Plot

16th Century Prague. In divining the stars, the Rabbi Loew learns that trouble is approaching for the Jewish people. Soon afterwards, the Emperor decrees that the Jews be banished from the city for their cabbalistic practices. Rabbi Loew creates a golem, a man-shaped figure formed out of clay, and brings it to life with a magic word given to him by Astaroth and placed in a star on its chest. The golem saves the Emperor from a falling roof and earns a pardon for the Jews. Loew is forced to deactivate the golem when the astrological configuration passes and it begins to assert its own will. However, Loew’s assistant Famulus, jealous of Loew’s daughter Miriam’s entertaining the knight Florian, revives it. This time the golem goes out of control, pursuing Miriam through the city.

Paul Wegener is an interesting figure in early German silent cinema. The huge-set actor began in Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theatre and soon moved to film, playing the title role of the student haunted by his doppelganger in the classic version of The Student of Prague (1913). Wegener, co-directing with screenwriter Henrik Galeen, the author of Nosferatu (1922), then went onto make his first version of The Golem (1914) based on the sixteenth century Polish Jewish legend. In that film, Wegener played the golem in present day surrounds, brought to life by an antique dealer who recognises it as Rabbi Loew’s creation, where he also got to pursue Lyda Salmanova (Wegener’s wife, this time playing the antique dealer’s daughter) through the city.

The Golem was a hit in Germany, although its success outside the country was curtailed by the arrival of World War I. That film seems to have been inspired by the serialisation of Gustav Meyrink’s popular novel The Golem (1913-4), although this was not an adaptation but one that claims to go back to the legends. All prints of the 1914 The Golem appear to have been lost today and only a few stills remain. Paul Wegener also played the clay one in a further film, The Golem and the Dancing Girl (1917), also lost today, about which only the slimmest of plot descriptions exist any longer. There Wegener apparently played a man who merely disguises himself as the golem as part of an elaborate ploy to seduce a dancer. There was also the purported Alraune and the Golem (1919), although this does not appear to have ever been made.

Following the War, German fantastic cinema blossomed following the amazing success of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919). Dr Caligari created a vogue for magnificent, extravagantly theatrical fantasies, built with colossal sets and stylized fantastical settings, usually drawing on Mediaeval legends. Around this time, F.W. Murnau made Nosferatu and Faust (1926), while Fritz Lang emerged with films like Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (1922), Siegfried (1924) and Metropolis (1927).

During this period, Paul Wegener was given the opportunity to rework The Golem with a more lavish budget. This version is usually called a remake but is more what we would today call a prequel to the first film. This tends to get lost in the English-language prints that call this version simply The Golem but is emphasised more so by the original German subtitle, which translates as How He Came Into the World.

Seen today, The Golem‘s value remains as more as a work of historic interest than anything else. Modern audiences tend to greet the vision of Paul Wegener clomping about in platform heels and starched wig as a comical rather than an horrific sight. However, The Golem is a good story and Wegener and Carl Boese’s direction is exceptional. There is a particularly good scene involving the calling up of Astaroth with Loew creating a flaming circle around a pentacle and conjuring forth a masked head that utters a breath of smoke out of which unrolls a piece of paper with the name on it. The scene where Loew creates a vision for the emperor’s court and the Golem saves them from a falling roof is also magnificently staged. The sets are also highly impressive, drawing as they do on the stylised, exaggerated lines of design created by Caligari.

Paul Wegener directed several other films. His only other venture into fantastic cinema was a lost version of The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1917). Up until his death in 1948, Wegener played a number of other sinister roles in German fantastic cinema including the title role (based on Aleister Crowley) in The Magician (1926), the title role in The Strange Case of Captain Rampar (1927), the scientist in the Henrik Galeen-directed remake of Alraune (1928) and a killer in Tales of the Uncanny/Unholy Tales (1932).

Further versions of the Golem legend are:– the French The Golem (1936); the Polish The Emperor’s Baker (1951), which turns the story to comic purposes; the cheap American horror film It (1966); an episode of the Czech portmanteau film Nights of Prague (1968), which retells the same basic story as here; and Israeli Paz Brothers’ retelling with The Golem (2018). There was also the The X Files episode Kaddish (1997) and the idea was played for comedy in the Terry Pratchett mini-series Going Postal (2010). The Polish sf film Golem (1980) has nothing to do with the legend of the golem and is a dystopian work about the creation of artificial people. The monster movie trilogy – Majin, Monster of Terror (1966), The Return of Giant Majin (1966) and Majin Strikes Again (1967) – is a Japanese variant on the Golem legend. The film is also often cited as the inspiration for Boris Karloff’s slow, stumbling artificial creation in Frankenstein (1931). (For a more detailed listing see Golems).

Full film available here