Crew

Director – Ridley Scott, Screenplay – David Mamet & Steven Zaillian, Based on the Novel Hannibal (1999) by Thomas Harris, Producers – Ridley Scott, Dino De Laurentiis & Martha De Laurentiis, Photography – John Mathieson, Music – Hans Zimmer, Visual Effects Supervisor – Emma Norton, Visual Effects – Mill Film, Special Effects Supervisor – Kevin Harris, Makeup Effects – Greg Cannom & Keith Vanderlaan’s Captive Audience, Production Design – Norris Spencer. Production Company – Universal/MGM/Dino De Laurentiis Corporation/Scott Free.

Cast

Anthony Hopkins (Dr Hannibal Lecter), Julianne Moore (Agent Clarice Starling), Giancarlo Giannini (Inspector Rinaldo Pazzi), [uncredited] Gary Oldman (Mason Verger), Ray Liotta (Paul Krendler), Zeljko Ivanek (Dr Cordell Doemling), Frankie Faison (Barney), Francesca Neri (Allegra Pazzi), Hazelle Goodman (Evelda Drumgo)

Plot

Clarice Starling is disgraced at the FBI after a botched drug sting operation. She is then placed back on the Hannibal Lecter case at the instigation of wealthy Mason Verger, one of the Lecter’s former victims, a paedophile whom Lecter persuaded to slice his face off, and who now wants revenge. In Florence, police inspector Rinaldo Pazzi realises that Lecter is posing as Dr Fell, an arts academic. Rather than inform the FBI, Pazzi sells the information to Verger. However, Verger’s attempts to capture Lecter go wrong and Lecter escapes, returning to the USA. There Verger, with the help of a corrupt Justice Department official, frames Clarice in an attempt to draw Lecter out and capture him.

Making a sequel to a film like The Silence of the Lambs (1991) is a daunting prospect. A film that was as successful and as popular with the public as The Silence of the Lambs was has a hefty reputation to live up to. The road to Hannibal was a difficult one. A bidding war erupted around the publication of Thomas Harris’s novel in 1999, with the rights finally being picked up by Dino De Laurentiis for a cool $10 million. (Dino De Laurentiis also produced Hannibal Lecter’s first screen outing Manhunter (1986) but that was not a success and, in a decision he must have kicked himself over later, De Laurentiis declined buying the rights to Thomas Harris’s next novel – The Silence of the Lambs [1988]).

A long time ago, even before the publication of Hannibal, Anthony Hopkins decided he did not want to reprise the role after he found children idolising Lecter but by the time of the film (not to mention a tidy percentage deal) he had clearly changed his mind. Then there was Jodie Foster who in grandly prima donnaish style waved around reasons such as that Clarice would never join Lecter’s cannibal feast at the story’s ending, as well as commitments to another project (which promptly fell through).

This was followed by Jonathan Demme and Ted Tally, the original director and screenwriter of The Silence of the Lambs, both declining the offer to be involved in Hannibal (although this author may be one of the few people who cheered the decision). Other screenwriters also declined involvement, claiming the book’s ending in particular made it unfilmable. Then there were the spiralling production costs – in part due to various people claiming percentage deals of the profits and the hefty cost of the rights – that bumped the budget up to $80 million, such that the production was underwritten as a joint venture between two studios, Universal and MGM.

Hannibal finally emerged ten years to the day after The Silence of the Lambs was released. As is the case when there is a classic to measure up to, responses to Hannibal were mixed. There were the usual moronic critical knee-jerk responses, latching onto the grisliness of the ending – attacking a film like for being grisly is like condemning The Sound of Music (1965) for being saccharine or Gone with the Wind (1939) for being romantic, it comes with the territory. Many others leapt on the problems that the structure of the book forced on the film – the sidelining of Clarice Starling for a better part of the story and offering glib “Maybe Ridley Scott signed on for the trip to Florence”-type reviews. Audience response was mixed, although not enough to stop Hannibal from earning the third highest ever box-office opening weekend and the highest ever for an R-rated film at that time.

Whatever the case, there is one unequivocal fact about Hannibal – it is a film that lives or dies depending on whether it succeeds in being a sequel to The Silence of the Lambs. (Although this reviewer’s opinion may be somewhat different to most as I found The Silence of the Lambs to be overrated. See above link for comments). Certainly, as an adaptation of its source novel, Hannibal works surprisingly well. Indeed, of all Thomas Harris’s novels adapted to the screen, this one treats the source material with the greatest degree of respect.

The script comes from two high-power screenwriters – Steven Zaillian, writer of Awakenings (1990), Schindler’s List (1993), Gangs of New York (2002), American Gangster (2007) and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) and director of Searching for Bobby Fischer (1993), A Civil Action (1998) and All the Kings Men (2006), and playwright David Mamet, author of the likes of The Untouchables (1987), Hoffa (1992) and Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) and director/writer of films like House of Games (1987), The Spanish Prisoner (1997), The Winslow Boy (1999) and State and Main (2000).

Mamet and Zaillian cut and tighten the book, sometimes reordering events, but mostly leave it intact. The scenes with the Evelda Drumgo drug sting, the encounter with Barney and the Pazzi hanging are all there exactly as they were conceived on the page, almost word for word. There have been some notable excisions though – such as the elimination of the entire character of Verger’s lesbian sister Margot, presumably for fear of treading across the same PC line that had The Silence of the Lambs condemned as offering homophobic stereotypes.

The most controversial of the changes is the ending. In the book, Thomas Harris had Lecter hypnotising Clarice and they feasting on Krendler’s brain together before becoming lovers and departing on an international romance. It was a decidedly dark ending that had fans puzzled and dubious – Thomas Harris was logically playing off the underlying sexual tension that existed between the two characters. Whether it should have been is the big question. And in truth it is too complex an ending to work on film – if it can puzzle and confuse on the page then in a more simplified arena like film it would have unquestionably left audiences on a downer. To the film’s credit, the new ending that has been created works well. Mamet and Zaillian retain the essence of the banquet but leave Clarice as an unwilling observer rather than a hypnotised participant, while briefly teasing with but eventually leaving the sexual tension hanging. There is the addition of a more upbeat ending that leaves Lecter still on the loose. The film goes out on a witty scene where Mamet and Zaillian have deftly transplanted and altered somewhat an earlier funny throwaway scene from the book with Lecter encountering a boy on a plane.

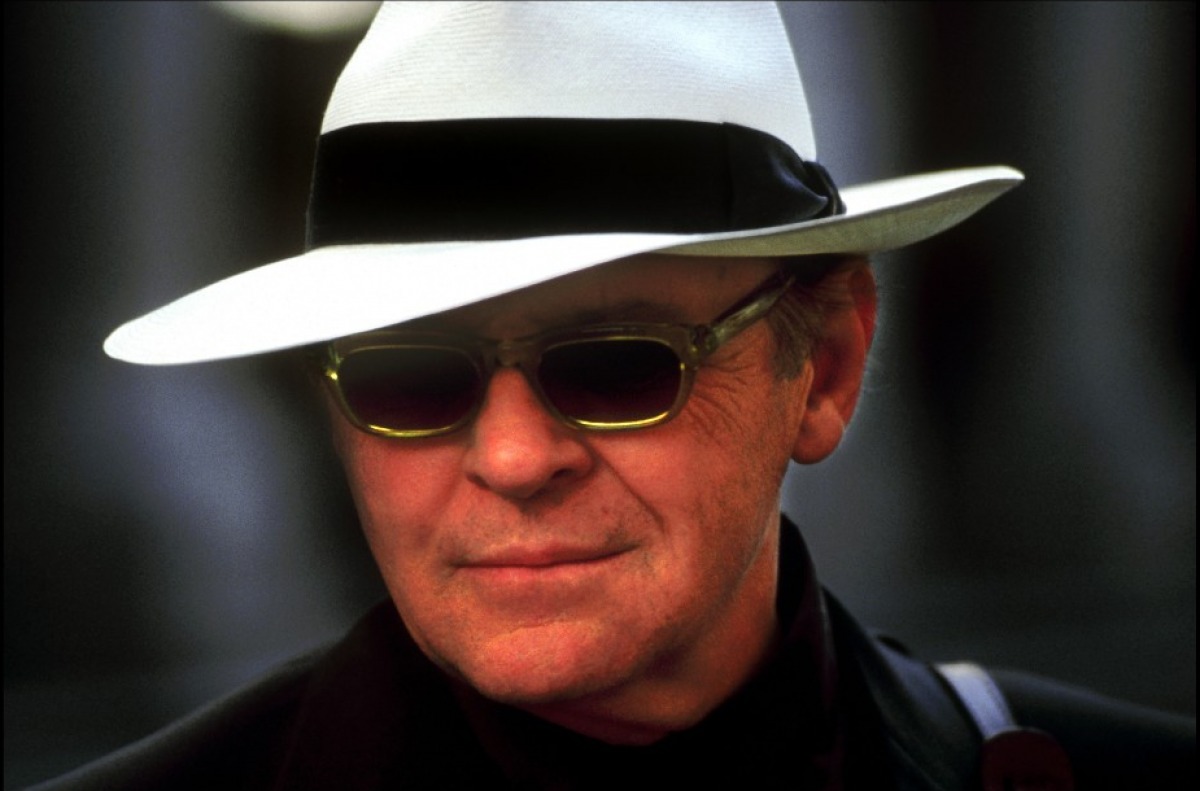

Dino De Laurentiis has hired Ridley Scott as director. Originally a commercials director, Ridley Scott is an extraordinary visual stylist, although is sometimes weak when it comes to story. Scott has made three exceptional genre films – Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), both of which fall into many people’s list of top science-fiction films, and the underrated adult fairtytale Legend (1985). Since this triptych, Ridley Scott’s career has dawdled through visually slick but often superficial films such as Someone to Watch Over Me (1987), Black Rain (1989), 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992), White Squall (1996), G.I. Jane (1996) and Black Hawk Down (2001), with occasional standouts like the great anarchist feminist fantasy Thelma and Louise (1991). Scott had a big hit the year before Hannibal with the runaway box-office phenomenon of Gladiator (2000). He would subsequently go onto make the likes of Matchstick Men (2003), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), A Good Year (2006), American Gangster (2007), Body of Lies (2008), Robin Hood (2010), The Counselor (2013), Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), All the Money in the World (2017), House of Gucci (2021), The Last Duel (2021) and Napoleon (2023), plus several other returns to genre material (see below).

Hannibal is a mixed effort. Whatever snide comments people make about Scott signing on for the trip to Florence, he certainly makes ravishing pictographic use of its locations, as well as of the rainy Vermont countryside. On the other hand, Hannibal never truly grips. Scott never has you on the edge of the seat or rattles you with full-on shock sequences the way he did in Alien (the exception being the banquet climax, which has a genuine ick factor that stirs up the audience).

Part of the problem with Hannibal is Thomas Harris himself. Hannibal was an absorbing book because Harris is incapable of not writing a compulsively gripping story. However, out of Thomas Harris’s four published novels to that point, Hannibal was also the weakest. The dramatic flaws of the book tend to be manifest to a greater degree up on the screen – namely that the two characters from the first story are kept apart for about two-thirds of the story with Clarice almost entirely dropping out of the picture until about halfway through.

The Silence of the Lambs had the guaranteed compulsiveness of the story of a woman entering into the lair of a criminal genius who, even though imprisoned in a cell, wound the entire game around him like a spider would a fly. Hannibal rarely finds that same compulsiveness. Steve Zaillian and David Mamet are not unaware of this failing and tighten a few of the scenes in compensation – notably placing the focus in the Florentine scenes on the tension between Pazzi and Lecter as he tries to obtain fingerprint evidence. They also invent a sequence of events over the book with Lecter entering Clarice’s home and leading her on a trail through the DC railway station. Although these scenes intermittently create a sense of cat and mouse suspense, the film never holds you in a dark thrall the way one expected it should have. What Hannibal feels like is a competent run through of the book. Crucially though, it never grabs you with a hold in the back of the head and never lets go the way that Thomas Harris’s books do, the way that Ridley Scott’s Alien did.

Hannibal was a considerable success at the box-office. Capitalising on this, Dino De Laurentiis then cannily went back and remade Manhunter with Anthony Hopkins as the superior Red Dragon (2002) and followed this with the Hannibal Lecter origin story Hannibal Rising (2007). The Hannibal Lecter saga was further elaborated in the excellent tv series Hannibal (2013-5) starring Mads Mikkelsen in the title role, which reintroduced the character of Mason Verger (played by Michael Pitt) along with his sister Margot (Katharine Isabelle) during its second season and restaged a number of elements from the book – Hannibal posing as an Italian academic, the character of Inspector Pazzi (Fortunato Cerlino) and his death, the bounty offered by Verger, Lecter joined by a hypnotised female companion – during its third season, albeit in slightly different ways. There was also the subsequent tv series Clarice (2021) telling the further adventures of Clarice Starling (Rebecca Breeds).

The climactic dinner was parodied in Scary Movie 2 (2001).

Ridley Scott’s other genre films include Alien (1979), Blade Runner (1982), the adult fairy-tale Legend (1985), the Alien prequels Prometheus (2012) and Alien: Covenant (2017), and The Martian (2015) about an astronaut stranded on Mars. Scott has also produced the erotic horror anthology series for cable tv The Hunger (1997), the psycho black comedy Clay Pigeons (1998), the historic Tristan + Isolde (2006), the tv mini-series remake of The Andromeda Strain (2008), the heart transplant horror film Tell-Tale (2009), the tv mini-series remake of Coma (2012), the tv mini-series Labyrinth (2012) about the quest for the Holy Grail, the horror film Stoker (2013), Child 44 (2015) about the hunt for a serial killer in Stalinist Russia, the videogame-adapted web-series Halo Nightfall (2014), the dystopian sf film Equals (2015), the tv series adaptation of The Man in the High Castle (2015-9), the artificial intelligence film Morgan (2016), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), the Found Footage UFO film Phoenix Forgotten (2017), the true-life-based tv series Strange Angel (2018-9) about pioneering rocketry and occultism, the Arctic horror tv mini-series The Terror (2018-9), the android film Zoe (2018), the BBC mini-series version of A Christmas Carol (2019), the planetary colonisation tv series Raised By Wolves (2020-2) and the true crime film Boston Strangler (2023).

(Nominee for Best Adapted Screenplay at this site’s Best of 2001 Awards. No. 8 on the SF, Horror & Fantasy Box-Office Top 10 of 2001 list).

Trailer here