UK/Czech Republic/France/Italy. 2007.

Crew

Director – Peter Webber, Screenplay – Thomas Harris, Based on His Novel Hannibal Rising (2006), Producers – Tarak Ben Ammar, Dino De Laurentiis & Martha De Laurentiis, Photography – Ben Davis, Music – Ilan Eshkeri & Shigeru Umebayashi, Visual Effects Supervisor – Alain Carsoux, Digital Visual Effects – Duboi, Special Effects Supervisor – Paul Dunn, Prosthetics – Amalgamated Extras, Production Design – Allan Starski. Production Company – Dino De Laurentiis Company/Quinta Communications/Ingenious Film Partners/Zephyr Films (Young Hannibal) Ltd/Etic/Carthage Films.

Cast

Gaspard Ulliel (Hannibal Lecter), Gong Li (Lady Murasaki), Rhys Ifans (Vladas Grutas), Dominic West (Inspector Popil), Richard Brake (Enrikas Dorlitch), Kevin McKidd (Petras Kolnas/Clobert), Charles Maquignon (Paul Momund), Stephen Walters (Zigmas Milko), Ivan Marevich (Bronys Grentz), Aaron Thomas (Young Hannibal), Helena Lia-Tachovska (Mischa Lecter), Richard Leaf (Father Lecter)

Plot

Lithuania, 1944. The Lecter family flee their castle in the face of the Nazi invasion on the Eastern Front. They take refuge in a cottage but the parents are killed by aerial fire, leaving eight-year-old Hannibal and his younger sister Mischa to fend for themselves. However, the cottage is invaded and they are taken prisoner by six deserting Nazi collaborators who are very hungry. Eight years later and a teenage Hannibal escapes from a Soviet school that has been housed in the commandeered castle. He makes his way across Europe in search of the uncle whose name he finds on family letters. In France, he finds that his uncle has died, but is welcomed in by his uncle’s Japanese widow Lady Murasaki. Hannibal and Lady Murasaki become very close. She teaches him the way of the samurai sword. Hannibal uses this to kill a vulgar butcher that insults her. They move to Paris where Hannibal becomes the youngest ever person to be accepted as a medical student at the Instituit de Medicine de St Marie. Using sodium pentothal, Hannibal is able to remember back to what happened in Lithuania when the six men killed and ate Mischa. He returns to Lithuania and kills one of the men in revenge, cooking and eating the man’s cheeks. From there, he learns that the other men are now in France and returns on a bloodthirsty vengeance trail.

The Silence of the Lambs (1991) is one of the modern classics of the psycho-thriller genre, even if this author feels it is overrated. The Silence of the Lambs was a massive success and garnered a host of Academy Awards, including winning Best Film and a Best Actor Award for Anthony Hopkins in his role as the infamous Dr Hannibal Lecter.

The Silence of the Lambs took the psycho-thriller genre away from the mould formed by Agatha Christie, the hard-boiled detective stories of Raymond Chandler and sundry tv imitators that built on these. In its place, The Silence of the Lambs introduced forensic profiling and the use of miniscule scientific and psychological clues to track criminals – this fascination has become so prevalent that current tv schedules feature dozens of shows centred around forensic detectives of some type – CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (2000-15) and spinoffs, NCIS: Naval Criminal Investigative Service (2003– ), Cold Case (2003-10), Bones (2005-17). The other thing that The Silence of the Lambs brought to the forefront of public attention was the notion of and the indeed the very term ‘serial killer’. Previously, cinematic killers had been defined in terms of improbable and outdated Freudian traumas.

In the horror genre, such success cannot go without being sequelized. Enter Dino De Laurentiis and the Hannibal Lecter saga’s convoluted production history. Prior to The Silence of the Lambs, Dino De Laurentiis had filmed The Silence of the Lambs author Thomas Harris’s previous book Red Dragon (1981) as Manhunter (1986) with Michael Mann as director. Hannibal Lecter features as a minor character in the book and was played by Brian Cox in the film. Manhunter was not a financial success and so Dino De Laurentiis passed over the option to film Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs (1988) in which Hannibal Lecter was made into the central character. The Silence of the Lambs was then filmed under Jonathan Demme and the rest is history.

However, when Thomas Harris published his long-awaited Silence of the Lambs sequel Hannibal (1999), Dino De Laurentiis was at the top of the queue in the bidding war that ensued for the rights and won out because of his prior relationship with Harris. De Laurentiis filmed the book as Hannibal (2001) with Anthony Hopkins making a return performance as Lecter and Ridley Scott in the director’s chair, although this met with considerable disappointment from almost all fans of the original. Buoyed by the considerable box-office success of Hannibal, Dino De Laurentiis then went back and remade Manhunter as the passable Red Dragon (2002), also starring Anthony Hopkins. (Here though, the story of Red Dragon had been amplified to make Hannibal Lecter into the central character).

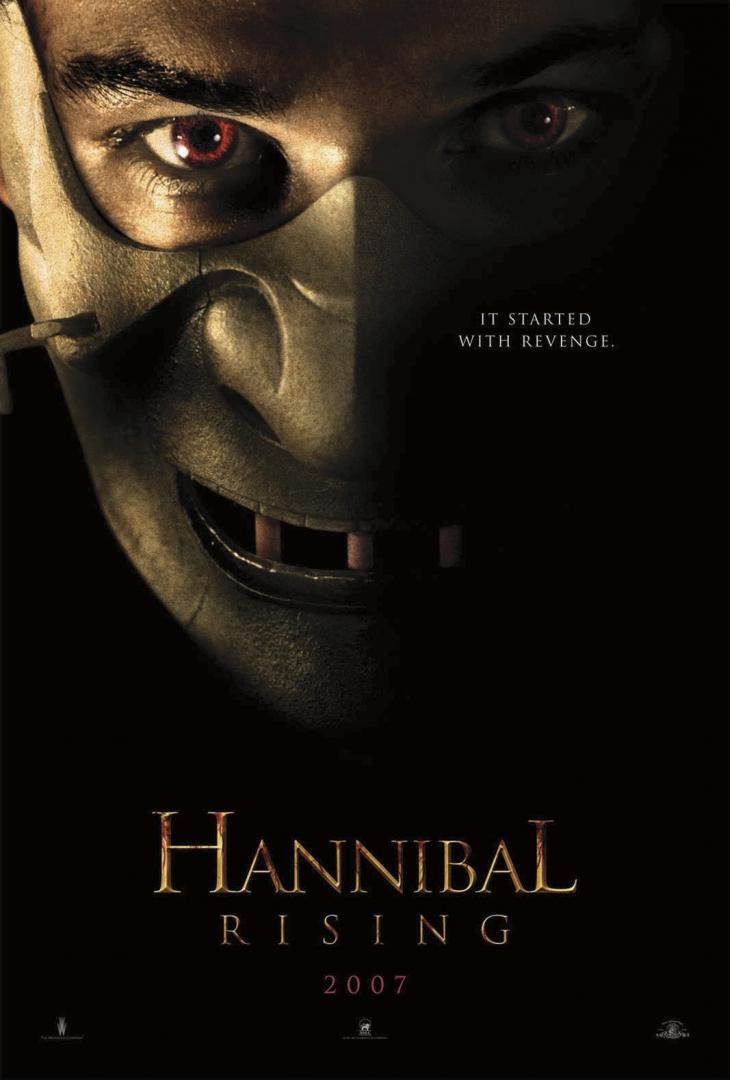

Hannibal Rising is a fifth Hannibal Lecter film and sets out to tell a Lecter origin story. The film circulated for a time under the title of Young Hannibal where the filmmakers had the idea of bringing Anthony Hopkins back and digitally altering his features to make him seem younger, but this never went ahead. Dino De Laurentiis commissioned a screen treatment from Thomas Harris, which became the credited screenplay. At the same time, Harris also developed this as a novel Hannibal Rising (2006). However, upon publication, the book received some astonishingly blistering reviews from fans of the other works – largely because, among other things, it is only novella length and was published in large print in order to pad it out to novel length. Quite whether the book can be regarded as a novelization of the film or the film an adaptation of the book (as the end credits claim) is a debatable point.

Hannibal Rising opened to some expectedly bad reviews in the US (as had both Hannibal and Red Dragon before it). There were all the usual accusations of it being grisly and disgusting (as though people going see a film that they know is about a cannibal would expect a work of delicately refined sensibilities). The role of the young Lecter has been recast with 24 year-old French newcomer Gaspard Ulliel and the director is the British Peter Webber, a former editor whose only other film previously had been the exquisite Girl with the Pearl Earring (2003).

Hannibal Rising is a mixed bag. I enjoyed reading Thomas Harris’s earlier novels – Black Sunday (1975), Red Dragon and The Silence of the Lambs – immensely. There Harris showed a mastery of suspense with tightly wound plots that had a gripping ability to get inside the detail of the investigation and a series of electric twists that snuck up with genuine surprise. This was flagging by the time of Hannibal, which lacked the same tightness and pace. I had never gotten around to reading Hannibal Rising prior to seeing the film so am unable to comment there.

On screen however, Thomas Harris seems to have created a sprawling plot that moves between various parts of Europe and post-War eras but never settles in with the same compulsive grip that his earlier works had. While Thomas Harris’s earlier works are tightly constructed thrillers, what we have here is little more than a revenge drama centred around Hannibal eliminating each victim. This is not a forensic thriller; it’s a variation on Death Wish (1974). There are few in the way of surprises and twists. More importantly, there is nothing in the film that delves into criminal psychology the way that Thomas Harris’s earlier Hannibal Lecter works did.

What we could also have done without is some of the more comic-book elements. Thomas Harris’s earlier Hannibal Lecter books revel in a fascination with forensic psychology, in examining and detecting minute behavioural clues. By the point of Hannibal Rising, Hannibal Lecter has almost become a comic-book super-villain – he is raised in a castle; is adopted by a lady aristocrat who worships traditional Japanese samurai culture and teaches the young Lecter in the ways of the sword; becomes the youngest person ever to be admitted to a prestigious medical academy; and develops ornately sadistic means of despatch against those who have wronged him. These are not the kind of motivations that drive real-world serial killers like Ted Bundy or John Wayne Gacy; rather it is the background characterisation that might be offered up for a DC or Marvel Comics super-villain.

Sometimes an author creates a character that ends up surpassing their original creation in the public mind and taking on a life of its own – you could point to examples like Wes Craven’s original conception of Freddy Krueger that subsequently developed into something else entirely, or Ian Fleming’s James Bond, Count Dracula and Batman. Hannibal Lecter may also be one of those characters where the public fascination with the character far outstrips the author’s conception. The public perceive Lecter through Anthony Hopkins’ demoniac performance, whereas Thomas Harris seems to appreciate Lecter on an entire different level.

By the time that he wrote Hannibal, Harris seemed in two minds about Lecter. On one hand, he had created a monster; on the other hand, Lecter started to increasingly seem like an alter ego for Thomas Harris – Lecter embodied qualities (be they an appreciation of classic art and fine dining, a genius mind that surpassed all mundane understanding and with a brilliant grasp of criminal psychology, amazing physical prowess, including the ability to control his autonomic responses, as well as a near-perfect memory) that one suspects were qualities that Harris wishes were his own. By the end of Hannibal, this divide played itself out in a peculiar ending that infuriated fans where, rather than continue to be a monster, Lecter became a romantic hero and swept Clarice Starling away.

In this admiration of Lecter’s qualities, Thomas Harris has had to end up justifying his actions as a cannibal psychopath. The way that he has done this is to reconceptualise Lecter as a just avenger – in Hannibal, Lecter seemed defensible or at least sympathetic because he was placed up against someone even more monstrous and inhumane – the millionaire paedophile Mason Verger; while in Hannibal Rising, the Lecter origin story is placed up against the shadow of what is often seen as the ultimate evil of the 20th Century – Nazi atrocities – and a group of viciously amoral thugs who are engaged in all sorts of crimes (including what looks like the current spectre of East European human trafficking) and, in particular, conduct the incredibly nasty act of eating the young Hannibal’s beloved sister.

In the majority of real-life serial killer cases on film – a good example might be Monster (2003) – you gain a glimpse into the flawed thinking of a serial killer and understand the damaged circumstances that forged them into what they are. However, Thomas Harris’s answer in conceiving an originating set of psychological circumstances for Hannibal Lecter is more one that casts his actions in the shadow of grim atrocities and then turns to the audience in effect saying “Wouldn’t you want to seek revenge for such things in the same circumstance?” You could perhaps contrast Hannibal Rising to Rob Zombie’s films House of 1000 Corpses (2003) and The Devil’s Rejects (2005), which feature backwoods hicks imprisoning and torturing innocents. Rob Zombie seems to say that nothing means anything, not even morality, so why not engage in murder, mayhem and sadism. Hannibal Rising does not seem too far removed from that, although Thomas Harris seems to disguise such an attitude behind a veneer of moral relativism – that it is okay to murder and torture and enjoy doing so as long as it is bad people that you are killing.

Hannibal Rising takes place without much involvement. Peter Webber never draws us into the suspense. All that seems to drive Hannibal Rising are a series of moderately grotesque murders at various intervals – Richard Brake in a faintly absurd scene where he is strung up to a tree and forced to sing a nursery-rhyme in German as a horse draws a noose tight around his neck; Ivan Marevich being drowned inside a med lab vat; butcher Charles Maquignon being sliced up and then beheaded by a samurai sword. Contrary to what most of the lily-livered mainstream critics thought about Hannibal Rising being nastily grisly, I found it tame.

In fact, more often than not, Peter Webber seems to avoid the opportunity to go for the throat. Hannibal caused outraged with its climactic scene where we saw Lecter feasting upon the brain of a man. Despite ample opportunity here, there is never any scene of equivalent shock value. We get mention of how Richard Brake’s cheeks were eaten but there is nothing seen of this other than Gaspard Ulliel starting a cooking fire in the forest and then a desiccated severed head found with its cheeks missing. Despite such being a crucial event to the film, the scene where Lecter’s sister Mischa is killed and eaten is only implied. We see nothing more of this than the men dragging her outside and wielding an axe – no cooking, no blood, no eating, nothing.

All that we end up with is an ordinary revenge plot that broods with darkness and perverse pleasures but critically fails in ever drawing us into the places it inhabits. In an era where such sadistically extreme films as Hostel (2005) and the Saw sequels can get mainstream releases and where Hannibal can show the eating of a man’s brain, there seems no reason that Hannibal Rising should end up being so tame other than a failure of moral courage.

The film does get an effective performance out of Gaspard Ulliel as the young Hannibal where Ulliel manages to perfect an intense and menacing glare that leaves a certain chill. It is an obvious and theatrical performance but then so too was Anthony Hopkins’ performance as Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. The film also casts Chinese actress Gong Li as Lady Murasaki. [Gong Li also played Japanese in Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) and her previous Western role was as the love interest in Manhunter director Michael Mann’s Miami Vice (2006)].

Gong Li moves through the film with an aristocratic grace but her performance feels impassive and detached. The relationship between Lady Murasaki and the teenage Hannibal was one that you wanted to be drawn into despite yourself – it felt like it had perverse depths to it and it rings with the suggestions you could see of her moulding the young Hannibal’s mind. On the screen, it seems a relationship that brims with possibilities but one that is eventually left lingering and unfulfilled – Hannibal even turns away and rejects her embrace. Not unlike the potential that the film itself held.

Subsequently, the Hannibal Lecter saga was further elaborated in the excellent tv series Hannibal (2013-5) starring Mads Mikkelsen in the title role, while there was also the tv series Clarice (2021) telling the further adventures of Clarice Starling (Rebecca Breeds)..

Trailer here