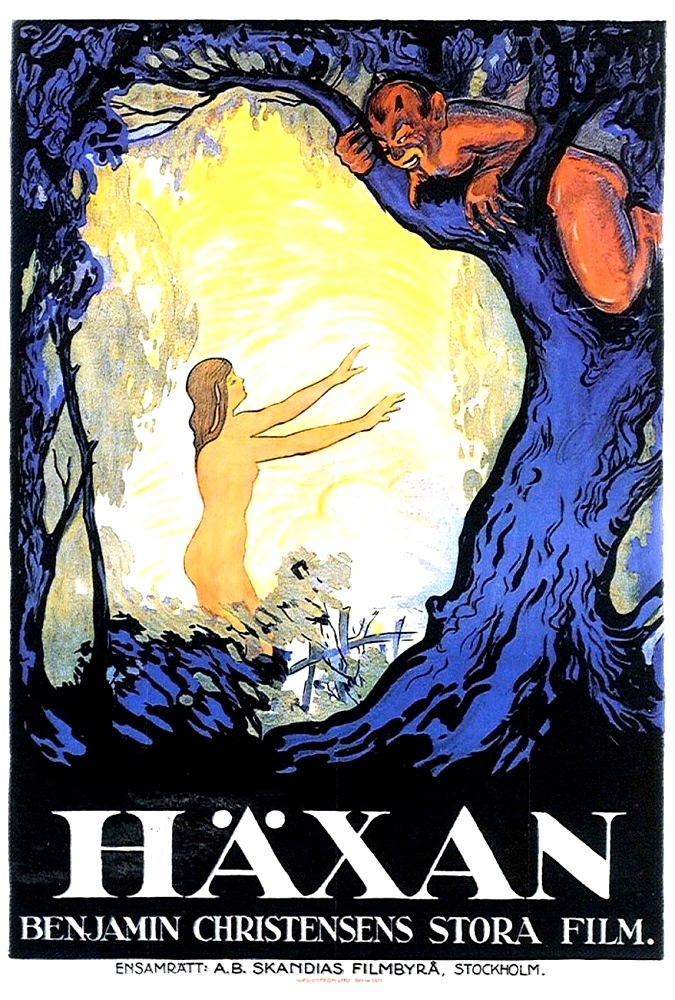

aka Witchcraft Through the Ages

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Benjamin Christensen, Photography (b&w) – Johan Ankerstjerne, Art Direction – Richard Louw. Production Company – Aljosha Production Company/Svensk Filmindustri.

Cast

Karen Winther (Anna), Emmy Schönfeld (Marie the Weaveress), Johs Andersen (The Chief Inquisitor), Elith Pio (Brother Johannes), Tora Teje (The Widow), Maren Pedersen (Karna), Benjamin Christensen (The Devil), Albrecht Schmidt (The Psychologist), Clara Pontopiddian (Nun)

This semi-documentary is a fascinating artifact from the silent era. For many years there was a great deal of difficulty in Häxan being shown due to its subject matter – witchcraft and Satanism – although today, after one has been jaded by the likes of The Exorcist (1973), it only seems tame. Häxan was reissued in 1966 with narration added by no less than William S. Burroughs and since then has taken on a new reputation and nowadays is often screened accompanied by live music, frequently of the Goth persuasion. It has gained a cult reputation, its name even being used as the production company by the directors of The Blair Witch Project (1999).

Director Benjamin Christensen divides the film into seven parts. The first is a straight lecture, which covers a history of witchcraft through the ages. The subsequent parts are sometimes interlinked stories that then illustrate Christensen’s treatise. As a documentary thesis goes, Häxan is not a particularly deep one – it makes the common mistake of equating witchcraft with Satanism, for one – and has more to do with Benjamin Christensen’s own speculations than with any great historical accuracy.

Nevertheless it is fascinating. This is none more so than when Christensen leaps off into illustrating accounts of what the witches were purportedly up to. There is an amazing sequence where we see a montage of scenes with them flying on broomsticks, dancing in the forest, cooking babies in cauldrons, being taken as the Devil’s lover and ritually kissing his ass, giving birth to his children, urinating into bowls and throwing the contents on a man’s door as a death curse and the like.

Equally fascinating are the scenes of the Inquisition in action – monks being whipped for sinful thoughts, nuns placing on belts of nails, an old woman stretched out on the rack. Here Benjamin Christensen takes us on a tour of the torture instruments used to extract confessions. The film is at its best during these scenes, when it forgets about being an illustrated documentary and heads off into dramatic narrative. The most shattering sequence is one where an innocent woman is lied to by the Inquisition and made to think she will be able to return to look after her child if she tells how to conjure rain.

The film’s end is fascinating. Here Benjamin Christensen carries the thesis through to the present-day and attempts to explain away much of the belief in witchcraft. This is illustrated with the dramatised case of an hysteric war widow who is driven to kleptomania and lighting fires in her sleep. Christensen makes fascinating analogies – between numb points on her back due to hysteria and the so-called witch’s marks; between flying on broomsticks and a biplane; between torture and the hysteric being placed in a hot shower by doctors to calm her down; between the entrance of The Devil through the window and the hysteric’s hallucination of a psychologist appearing through her window. Much of this imagery has more to do with fanciful visual connection than real explanation – in one scene, The Devil is equated with a psychologist, but Christensen then contradicts moments later by seeing the psychologist as the cure-all for the girl’s problems.

It is here that Benjamin Christensen’s thesis eventually becomes garbled. He wants to both have his cake and eat it too. He points to witchcraft and attempts to explain it away in modern psychological terms (although those terms are very naive ones when seen today), but then also tries to say that maybe there was some validity to witchcraft anyway, pointing to the modern prevalence of tarot and crystal ball readers as evidence. The effect is of a modern sceptic who denounces superstition as pure tosh but still steps over cracks in the pavement and avoids black cats just to be absolutely sure.

This is Christensen’s tone throughout the film – he seems to want to regard witchcraft as superstition that was created by an ignorant mindset and is cautiously horrified at the acts conducted by The Inquisition, but will not commit himself absolutely to saying they were wrong. And not far beneath there is something akin to a puritan being fascinated with the sins he condemns – Christensen decries witchcraft as nonsense but he also wishes it were real because he is fascinated with depicting it. Häxan is never fired up with greater flights of torrid imagination than when Christensen is depicting the blasphemous acts that the witches supposedly got up to.

Danish-born director Benjamin Christensen (1879-1959) came to film first as an actor. Later he went to Hollywood where he made several Old Dark House thrillers – The Haunted House (1928), the lost The House of Horror (1928) and Seven Footprints to Satan (1929), as well as uncredited work on the Jules Verne adaptation The Mysterious Island (1929).