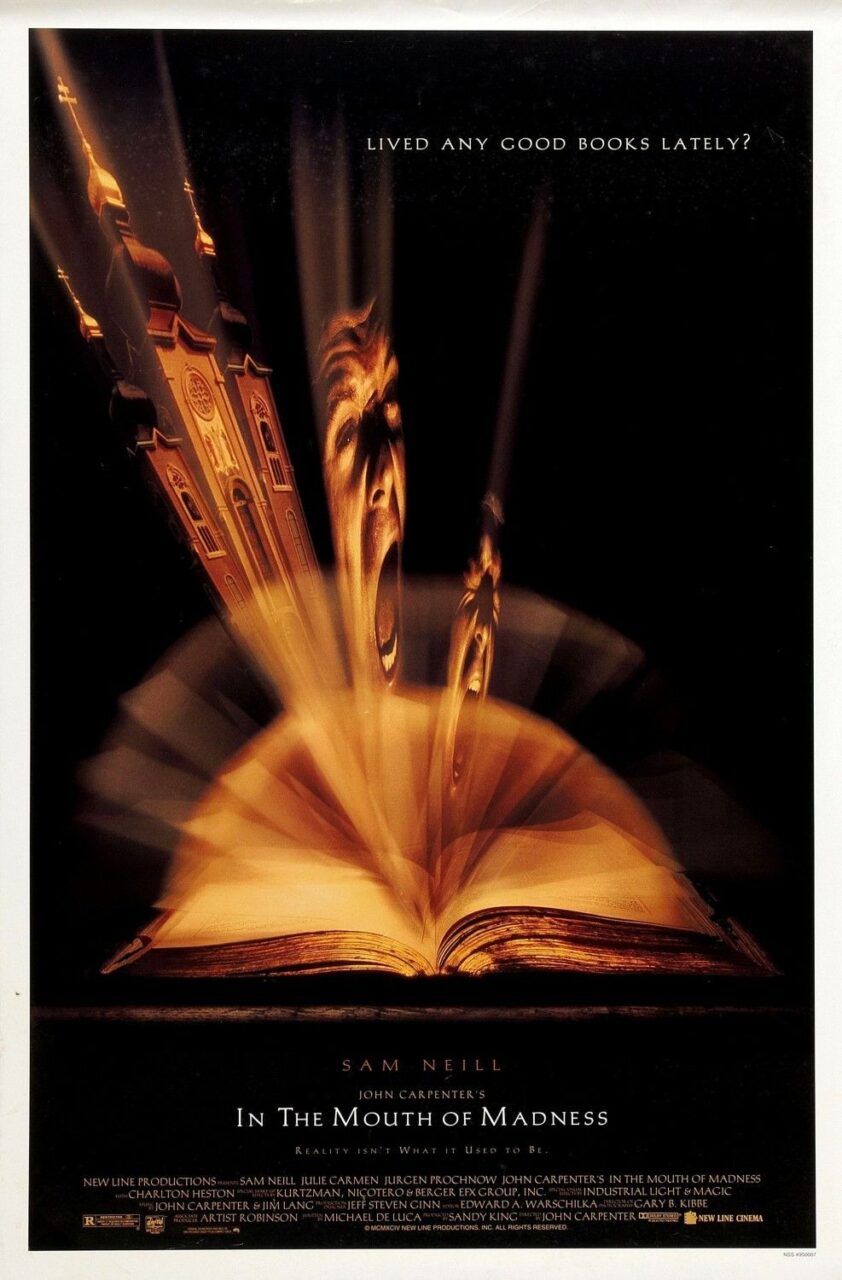

USA. 1995.

Crew

Director – John Carpenter, Screenplay – Michael De Luca, Producer – Sandy King, Photography – Gary B. Kibbe, Music – John Carpenter & Jim Lang, Visual Effects – Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Bruce Nicholson), Special Effects – Martin Malivoire Pictures & Ted Ross, Makeup Effects – Kurtzman, Nicotero and Berger EFX Group Inc, Production Design – Jeff Steven Ginn. Production Company – New Line Cinema.

Cast

Sam Neill (John Trent), Julie Carmen (Linda Styles), Jurgen Prochnow (Sutter Cane), Charlton Heston (Jackson Harglow), David Warner (Dr Wren), Frances Bay (Mrs Pickman), John Glover (Dr Sapirstein)

Plot

A psychiatrist goes to talk to private investigator John Trent where he is locked in a padded room in an asylum. Trent tells how he was hired by a publisher to find the missing horror novelist Sutter Cane. Cane believed that his work had become so popular that what he wrote was starting to become real. Trent then discovered that Cane’s book covers could be pieced together to give directions to a town in New England that was not on any map. Driving there with editor Linda Styles, Trent realized that it was Cane’s fictional town of Hobbs’ End come to life. The town was filled with nightmarish visions as reality kept blurring. Trent discovered that Cane had opened a gateway that allowed monsters from the abyss to roam free in this world.

Director John Carpenter was one of the genre greats of the 1970s and early 1980s. Carpenter became a cult name on the basis of Dark Star (1974) and Halloween (1978) and went onto deliver other fine works like Escape from New York (1981) and The Thing (1982). John Carpenter’s star began to fade toward the end of the 1980s where his films failed to garner the enthusiasm they once did. Into the 1990s and beyond, Carpenter’s output became more sporadic and exceedingly mediocre – the likes of Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992), Village of the Damned (1995) and Ghosts of Mars (2001). In the Mouth of Madness was one of the few brief spurts of inspiration from the old John Carpenter during this time. Like some of his other latter-day efforts, Prince of Darkness (1987) and They Live (1988), In the Mouth of Madness does not fire on all cylinders but flames with some great moments of imagination.

In the Mouth of Madness is John Carpenter’s attempt to make an H.P. Lovecraft film. H.P. Lovecraft had been popular on screen ever since the cult success of Re-Animator (1985). Since then we have seen such Lovecraft adaptations as From Beyond (1986), The Curse (1987), The Unnameable (1988), The Resurrected (1992), Necronomicon (1993) (a Lovecraft portmanteau film), Lurking Fear (1994) and Dagon (2001). The unfortunate thing about this mini-Lovecraft trend is that the type of film being made is anything but Lovecraftian in style. Lovecraft specialised in a cosmic psychological horror – a vision of humanity on a tiny island of light surrounded by a darkness of literally indescribable horrors, arcane rites and ancient gods who regarded humanity as less than fleas. There is a particularly dark and paranoid grip that H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic vision exerts on the imagination despite the turgidity of the prose it comes embedded in.

Unfortunately, the cinematic Lovecraft fad was everything that the written Lovecraft is not – instead of psychological horrors, it was splattery and often blackly comic in tone; instead of indescribable, its creatures all came upfront and in your face, leaving nothing to the imagination. Even though it is not based on any H.P. Lovecraft work, In the Mouth of Madness was easily the most faithful Lovecraft film made out of this cycle. The title is obviously intended to mirror H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1936) and the story is narrated, in typically Lovecraftian fashion, by a man in an asylum who has gone mad as a result of contact with the horrors out there.

In the Mouth of Madness also taps into the 1980s-90s cinematic fascination with elastic reality. Ever since A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), fantastic cinema had become fascinated with an increasingly tenuous view of reality, one that seems in imminent danger of being eclipsed and undermined by something from Elsewhere. This stretches from the dream invasions of Elm Street and its sequels and numerous clones, to the visions of cyberspace and VR indistinguishably supplanting reality in Open Your Eyes (1997), The Matrix (1999) and The Thirteenth Floor (1999), and the paranoid underminings of everything we know and the realization that truth is manipulated by organized conspiracy in tv’s The X Files (1993-2002, 2016-8) and imitators.

There is a certain sub-genus of these films that involve fiction taking over reality. There was Videodrome (1983) about tv becoming reality, and Demons (1985) and Anguish (1986), as well as more comic efforts like The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) and Last Action Hero (1993) about happenings on a cinema screen becoming mixed up with reality. In the literary horrors subgenre, there was I, Madman/Hardcover (1989), a decent little low-budgeter about a maniac emerging from a book to slaughter the friends of the reading heroine, and George Romero’s adaptation of Stephen King’s The Dark Half (1993) about a respectable literary writer whose secret alter ego as a writer of ultra-violent thrillers comes to life to haunt him. None of these films are as extraordinary as Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994), an Elm Street film purporting to be set in the real world, featuring the cast and production crews of the films playing themselves, where the Elm Street films were audaciously treated as rituals used to prevent a real horror escaping. (For more detail see Meta-Fiction Films).

John Carpenter and screenwriter, then New Line Cinema CEO, Michael De Luca, have fun with these meta-fictional games in In the Mouth of Madness. “Reality is just what we tell ourselves it is,” one character says, and the film goes on to suggest the intriguing notion that the popularity of a work of fiction has the capacity to bring it into reality. Alas, the idea is underdeveloped. John Carpenter and Michael De Luca never particularly engage either with the idea of a writer bringing his fiction to life, or expand out on the interesting sense of Lovecraftian horrors being unleashed from the abyss of time. The arrival at the town only serves as a stepping off point for John Carpenter to start producing a grab-bag of reality blurring tricks, while the film ultimately never grapples with the greater ideas that fuel these. Although there is a particularly appealing ending where Sam Neill wanders into a cinema and sits down to watch the same film that we have just seen.

In the Mouth of Madness is at its best in the latter half when John Carpenter is working on the level of visceral shocks rather than ideas and gets to unleash a series of vivid Lovecraftian horrors. He offers up some memorable images – a painting on the wall where the figures in it keep moving position whenever people are not looking; the moment the heroine reaches up to caress the face of the missing writer and the camera moves behind him to show that it is a tentacular monstrosity that is wearing his body like a marionette; the dithery old biddy who runs the hotel and keeps her naked husband handcuffed to her ankle under the desk; the scary moment where the hero valiantly tries to insist that he is not a work of fiction that may have been conjured out of the writer’s imagination to serve his purposes; and a sequence where Sam Neill is pursued by a massive horde of monsters from the abyss, which are all the more horrific for only being subliminally glimpsed, the one moment when the film goes some way to capturing the essence of H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘indescribable’ horrors.

The film is fun in these parts but on a wider thematic level In the Mouth of Madness is dissatisfying. Nor is it helped by a bad performance from Sam Neill. Sam Neill seems to reserve his bad performances for John Carpenter – the only other bad performance he gave was in Carpenter’s Memoirs of an Invisible Man. He is badly miscast as a quintessential private detective – the character is meant to be cynical and worldweary but the way Neill plays it he just comes out dopey.

Carpenter also throws in references to his revered Quatermass – he took the pseudonym Martin Quatermass on his script for Prince of Darkness – and here Cane’s fictional town is named Hobbs’ End, a reference from Quatermass and the Pit/Five Million Years to Earth (1967). There is also a ‘Dr Sapirstein’ named after the gynaecologist in Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and a Mrs Pickman, no doubt in reference to the Lovecraft story Pickman’s Model (1926).

John Carpenter’s other genre films are:– Dark Star (1974); the urban siege film Assault on Precinct 13 (1976); Halloween (1978); the stalker psycho-thriller Someone’s Watching Me (tv movie, 1978); the ghost story The Fog (1980); the sf action film Escape from New York (1981); the remake of The Thing (1982); the Stephen King killer car adaptation Christine (1983); the alien visitor effort Starman (1984); the Hong Kong-styled martial arts fantasy Big Trouble in Little China (1986); Prince of Darkness (1987), an interesting conceptual blend of quantum physics and religion; the alien takeover film They Live (1988); Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992); the horror anthology Body Bags (tv movie, 1993), which Carpenter also hosted; the remake of Village of the Damned (1995); Escape from L.A. (1996); the vampire hunter film Vampires (1998); the sf film Ghosts of Mars (2001); and the haunted asylum film The Ward (2010). Carpenter has also written the screenplays for the psychic thriller Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), Halloween II (1981), the hi-tech thriller Black Moon Rising (1985) and the killer snake tv movie Silent Predators (1999), as well as produced Halloween II, Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), the time-travel film The Philadelphia Experiment (1984), Vampires: Los Muertos (2002), the remake of The Fog (2005) and the reboot of Halloween (2018).

(Nominee for Best Makeup Effects at this site’s Best of 1995 Awards).

Trailer here