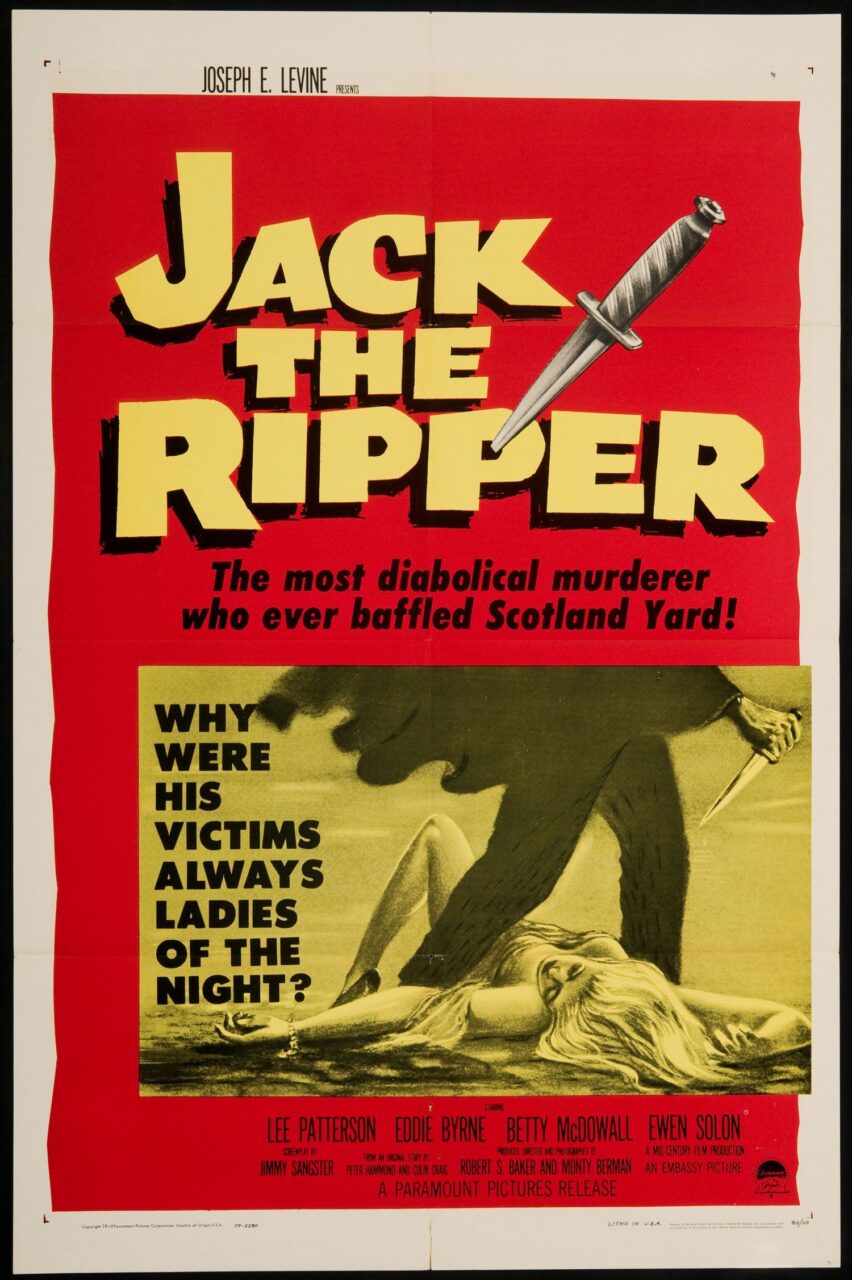

UK. 1959.

Crew

Director/Producers/Photography (b&w) – Robert S. Baker & Monty Berman, Screenplay – Jimmy Sangster, Story – Colin Craig & Peter Hammond, Music – Stanley Black, Makeup – Jimmy Evans, Art Direction – William Kellner. Production Company – Mid-Century Film Productions Ltd.

Cast

Lee Patterson (Sam Lowry), Betty McDowall (Anne Ford), Eddie Byrne (Inspector O’Neill), Ewen Solon (Sir David Rogers), John le Mesurier (Dr Tranter), Garard Green (Dr Urquhart), Philip Leaver (Music Hall Manager), Jane Taylor (Hazel), Barbara Burke (Kitty Knowles), Endre Muller (Louis Benz), Jack Allen (Assistant Commissioner Hodges), Denis Shaw (Simes), Bill Shine (Lord Tom Sopwith), Anne Sharp (Helen), George Rose (Clarke), Esma Cannon (Nelly)

Plot

London, 1888. The city is being terrorised by the Jack the Ripper killings. Amid public outcry that accuses the police of incompetence, Inspector O’Neill is overworked but has no clues. He is joined by Sam Lowry, a police colleague from America. Lowry becomes attracted to Anne Ford, the ward of surgeon Dr Tranter, who has volunteered for a job at the Whitechapel hospital. Various other girls from local bars and dancehalls become victims to the killer who is searching for a Mary Clarke. In O’Neill and Lowry’s search, it becomes apparent that this is someone with medical expertise and may be working at the hospital.

The Jack the Ripper killings were not the first serial killings in modern history but were the first to inflame the public imagination. Although there is some dispute as to how many murders there were (with some Ripperologists adding other potential victims), almost all agree that there were five canonical victims who were slaughtered between August and November of 1888. The name Jack the Ripper came from numerous letters mailed to the press supposedly written by the killer who signed himself as such in one letter (although these were believed to be faked by a journalist). The killer was never caught, which is part of the fascination of the case. There have been an enormous number of suspects, many coming from those who fell under the police eye back during the day, many that have emerged since. This has led to a vast industry of historical speculation from suspects that range from the credible to more fanciful fictions and conspiracy theories – such as that the women were assassinated to cover up a dalliance by a member of the Royal Family; that the Ripper was Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland (1865); and more recently, the James Maybrick diary hoax.

Jack the Ripper has had a strong afterlife on film, almost none of which bears any resemblance to the events that happened historically. Prior to this film, the only treatments had been the Alfred Hitchcock silent film The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927), which had thrice been remade as The Lodger (1932), a sound version of the Hitchcock film, The Lodger (1944) with Laird Cregar and Man in the Attic (1953) with Jack Palance. However, The Lodger was less about the Jack the Ripper killings than the story of a household believing that their tenant might be the killer where the Ripper’s crimes and victims had been heavily fictionalised. (See below for other treatments of the Jack the Ripper story on film).

Jack the Ripper is the most well-known film today from the British producing-writing-directing team of Robert S. Baker and Monty Berman. Baker and Berman had previously directed five non-genre British quota quickie thrillers together. The only other film they made of any note as directors was the moderately sensationalistic The Hellfire Club (1961). Baker and Berman had a far more substantial career as producers, mostly with thrillers but with a number of other genre productions including Blood of the Vampire (1958), The Trollenberg Terror/The Crawling Eye (1958), The Flesh and the Fiends (1960) and the comedy What a Carve Up! (1961). They later ventured into television, most famously with the Roger Moore The Saint (1962-9), the subsequent Roger Moore series The Persuaders (1971-2) and the Ian Ogilvy starring Return of the Saint (1978-9), while Berman on his own also produced The Champions (1968-9), Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) (1969-71) and Department S (1969-70). Jack the Ripper was brought up by US promoter Joseph E. Levine who had just had huge success with selling the Italian Hercules (1958). Levine planned similar things here – only for the film to flop at the US box-office.

Jack the Ripper has a script from Jimmy Sangster who was one of the key figures of the Anglo-Horror Cycle, having written The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958), the two films that were the cornerstones of Hammer’s success and a number of other subsequent works, particularly Hammer’s psycho-thrillers of the 1960s. I suspect that Jack the Ripper has always been pegged as an entry in the Anglo-horror cycle because of the Sangster name. It is but feels like it doesn’t belong. For one, the Hammer films and their imitators made a virtue of their lush colour and period settings and Jack the Ripper (while set in the Victorian era) is shot in black-and-white just like another of Baker and Berman’s low-budget quota quickies.

One’s main problem with Jack the Ripper (and before that the various versions of The Lodger) is that it is a cleaned-up and censored portrait of Whitechapel and Victorian London. Certainly, Jimmy Sangster does a fair job in his portrait of the cross-section of society – the angry and restless poor forming into mobs in the streets; the frustrated police; the upper-class at work in the poor hospitals. On the other hand, like The Lodger, entirely censored from this version is any mention of the fact that the Ripper’s victims were prostitutes and the film instead substitutes the fiction that they were dancehall girls and barmaids.

Moreover, the film has edited out any sense of just how desolate an area of town Whitechapel was. The area was what we would today call a slum whose people were the poorest of the poor, lived in appalling housing conditions (sometimes several people living in a single room with no amenities), and where the Ripper’s victims’ were destitute women who were selling their bodies to obtain a few shillings to get by each day in an area of only a few square miles that had a population of 1200 working prostitutes. The film seems to have erased this vision of the underside of Victoriana and painted the people more as the congenial working classes of 1940s/50s England.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment of the film is that Jimmy Sangster has not done much to research the Jack the Ripper casefile. (Although to be fair to him, at the time he was writing there was not the wealth of detail and minutiae of research on the victims, suspects and almost every facet of the case that there is easily available online today). The film goes for the old cliche of the Ripper suspected of being a doctor (supposedly because of the surgical precision of the cuts, although this notion was dismissed by the leading pathologist in the case) and as a shadowy figure in a top hat stalking Whitechapel with a black surgical bag (another cliche that has been disproved by eyewitness reports). Sangster eventually reveals the Ripper as [PLOT SPOILERS] a doctor from an upper-class background who, in a piece of cod-1940s B movie psychological motivation, is killing all women because a Mary Clarke caused his son to go astray.

Baker and Berman conduct an okay film. Their work never rises out of the passable but at least they conduct a vigorous atmosphere out of the gaslit Victorian setting and scenes of the Ripper lurking in the streets – where the black-and-white shooting gives the film a modest atmosphere. They seem the most at home during the dancehall sequences and produce an energetic showing that one feels would have been authentic for the era. (These also feature a number of topless sequences of the dancehall girls in their changing room – something that was quite adventurous for the era. These were immediately censored in the British release but remain in the French print and have been edited back in in the version that circulates on the internet today, albeit dubbed in French and subtitled).

The other Jack the Ripper films include:- those that conduct supposedly straight tellings of the details of the case such as the Spanish Jack the Ripper of London (1971) with Paul Naschy, Jess Franco’s Jack the Ripper (1976) with Klaus Kinski, Jack the Ripper (tv mini-series, 1988) starring Michael Caine, The Ripper (1997), the Alan Moore graphic novel adaptation From Hell (2001) with Johnny Depp, the German Jack the Ripper (2016), and Ripper Untold (2021) and its sequel Ripper’s Revenge (2023). There are a number of other works that feature The Ripper as a central character like The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927), The Lodger (1944), Room to Let (1950) and Man in the Attic (1953), although most of these vary widely from the known details. More prevalent have been speculative treatments, including the likes of:- having the contemporary but fictional figure of Sherlock Holmes solve the mystery in A Study in Terror (1965), Murder By Decree (1979) and Holmes & Watson: Madrid Days (2012); the Ripper being an alien spirit that possesses Scotty in Star Trek‘s Wolf in the Fold (1966) and with similar stories occurring in episodes of Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974-5) and The Outer Limits (1995-2002); the Ripper being Dr Jekyll in both Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) and Edge of Sanity (1989); Jack the Ripper’s daughter featuring in Hands of the Ripper (1971); H.G. Wells and the Ripper travelling through time to the present day in Time After Time (1979) and its tv series remake Time After Time (2017), as well as a time-travelling Ripper appearing in episodes of tv series like Fantasy Island (1977-84), Goodnight Sweetheart (1993-9) and Timecop (1997-8); The Ripper having travelled out West in the Knife in the Darkness (1968) episode of the Western tv series Cimarron Strip (1967-8) and the film From Hell to the Wild West (2017);The Ripper being resurrected or copycated in the present day in The Ripper (1985), Bridge Across Time/Terror at London Bridge (1985), Jack’s Back (1988), Ripper: Letter from Hell (2001), Bad Karma (2002), The Legend of Bloody Jack (2007), The Lodger (2009) and Whitechapel (tv mini-series, 2009); a parody segment of Amazon Women on the Moon (1987) that speculates that the Ripper was in fact the Loch Ness Monster; the Babylon 5 episode Comes the Inquisitor (1995) that reveals the Ripper was taken up by aliens and redeemed; transposed to Gotham City in the animated Batman: Gotham By Gaslight (2018); even turning up as a character in the French animated film Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart (2013). Also of interest is the tv series Ripper Street (2012-6), a detective series set in London in the immediate aftermath of the Ripper killings.

Trailer here