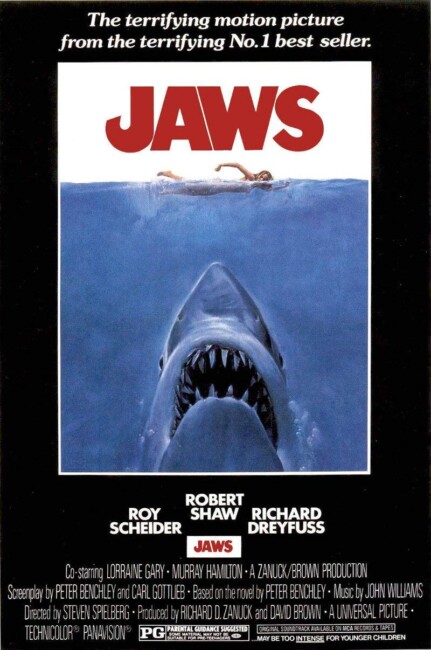

USA. 1975.

Crew

Director – Steven Spielberg, Screenplay – Peter Benchley & Carl Gottlieb, Based on the Novel by Peter Benchley, Producers – David Brown & Richard D. Zanuck, Photography – Bill Butler, Underwater Photography – Rexford Metz, Music – John Williams, Special Effects – Roy Arbogast, Robert Mattey & Bill Shourt, Production Design – Joseph Alves Jr. Production Company – Zanuck-Brown.

Cast

Roy Scheider (Police Chief Martin Brody), Richard Dreyfuss (Matt Hooper), Robert Shaw (Quint), Murray Hamilton (Mayor Larry Vaughn), Lorraine Gary (Ellen Brody)

Plot

The small beachfront town of Amity is hit by a sudden spate of killings at sea. Police chief Martin Brody determines that a shark is responsible but Mayor Larry Vaughn refuses to do anything as this will mean closing the beaches right on July 4th weekend and a drastic loss in tourist profit. However, when the killings hit a little close to home, they are forced to hire the professional hunter Quint. Joined by the nervously land-lubberish Brody and the bookish ichthyologist Hooper, Quint heads out onto the open sea where they engage in a hunt to kill the shark. This becomes a battle where the shark proves to have more cunning than they thought.

When Jaws came out, it became the No. 1 All-Time box-office champion in only 28 days (at least, until Star Wars (1977) two years later) and made a star out of its largely unknown director – a certain Steven Spielberg, age only 28. At that time, Steven Spielberg had only directed several episodes of various tv series and two films, the highly acclaimed tv movie Duel (1971), which was released as a cinematic feature, and the chase film The Sugarland Express (1974), which was acclaimed but little seen at the time.

Jaws came out of nowhere – promoted largely by the studio publicity conducting the then relatively new idea of taking out commercial tv advertising spots to promote the film – and its success surprised the whole world. It is a powerhouse of film made by someone who was young and bursting with talent. Spielberg demonstrates a real mastery – one that he has never fully demonstrated again – in detail, in character and most of all in the ability to manipulate the audience with shock and suspense.

Jaws comes in two parts. The first half is an elegantly elaborated Hitchcockian game of The Boy Who Cried Wolf, centred around Roy Scheider’s Everyman who fights to have the townspeople take the shark menace seriously. Though the film remains shorebound in these scenes, Spielberg builds the menace of the shark up highly effectively. He crafts scares with a superb elegance. He sends the film barrelling at you one way and then playfully pulls back from what you think is about to happen – like the scene where the frantically swimming fishermen finds what is pursuing him is only be a piece of driftwood – only to then sneak in from the side while you are not looking – the beach scene where a shark attacks children in a nearby inlet while everyone’s attention is diverted by children with a fake fin. The build-up is such that the audience is like putty when Spielberg pulls his actual jumps – the scene where Richard Dreyfuss dives on an abandoned boat and a head pops out from the hull never fails to make an entire theatre jump.

The latter half of Jaws becomes a skilfully tense variant on Moby Dick (1851) – and just a little bit of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1952) – a pursuit through the high seas against a nemesis that demonstrates almost superhuman guile. In this half, Steven Spielberg opens Jaws up into a powerhouse tour-de-force of shark-and-mouse games. The action is confined to a small boat, open to the sky and sea on every side, something that generates an uneasy sense of hydrophobia.

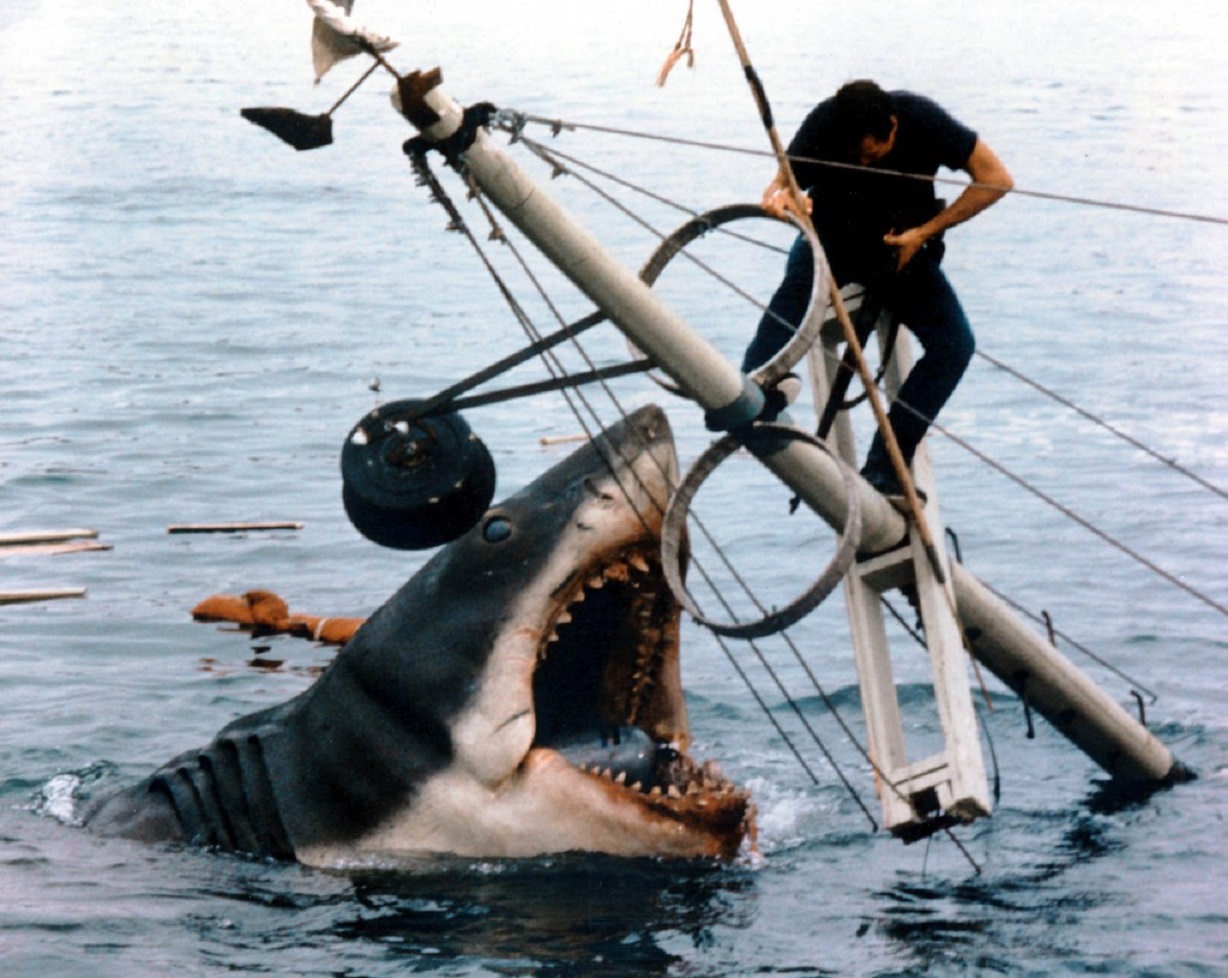

Once there, Spielberg and editor Verna Fields grip an audience with the giddy intensity of an unstoppable rollercoaster ride. The smoothness of the way they slip punches past takes your breath away – the casualness of the shark’s first appearance where Roy Scheider’s face is casually half-turned as he throws bait in the water – is a great shock jump. It is an intense seat-edge ride to eventually arrive at the point where the shark reduces the boat to a wreck with Roy Scheider reduced to fighting the shark with a paltry handgun while hanging onto the mast of the boat as it is rapidly sinking beneath the waves. There are few other films that put an audience through such a gruellingly intense workout.

It might have been interesting if Steven Spielberg had not made Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) straight after Jaws and then gone onto E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), forever solidifying his name as synonymous with childhood innocence. Maybe if Spielberg has not taken that route and continued in the line of films following Duel, The Sugarland Express and Jaws, he might have become a latter-day Hitchcock. Both Duel and Jaws are Lewtonian films at heart. In the 1940s, producer Val Lewton, with films like Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), patented the psychological horror film, a type of film that rarely featured actual monsters but instead were films that hung in an indeterminate place between reason and the supernatural, between whether characters were imagining the monsters or not.

Both Duel and Jaws are films where the menace remains shadowy – we never see the driver of the truck in Duel and in Jaws the shark only makes brief appearances, frequently only represented by a fin gliding through the water or a cluster of yellow barrels being dragged behind it. (In actuality, this was more due to coincidence than intention as Spielberg was not happy with the relative technical inexpressiveness of the mechanical shark, which led to enormous delays in production and the film spiralling massively over-budget from an initial $3.5 million to $10 million plus and a 55 day shooting schedule dragging out to nearly six months, and so the decision was made to cut the shark scenes to a minimum).

Almost as riveting as the suspense is the characterisation. In fact, this is an occasion where a film version of a book improves enormously upon the original written version. Peter Benchley’s original 1974 novel is a dull read. (In one interview, Spielberg made the amusing claim that he and one of the producers helped turn the book into a best-seller by each going out and buying a hundred copies). The film drops several subplots that make the characters a lot less likable on the page, most notably Hooper’s having an affair with Brody’s wife.

Jaws ended up making the career of the three principal actors. Roy Scheider gives a great performance. Scheider, a greatly underrated actor, always had the ability to effortlessly embody a likable Everyman. One of the finest scenes in the film has nothing to do with shock or suspense but is a beautifully small, quiet scene between Scheider and son sitting at a table, each imitating the others gestures in a silent mime. Richard Dreyfuss gives possibly his best performance ever as the twinklingly teddybearish Hooper. There is another fine performance from Murray Hamilton as the sheepishly hypocritical yet sympathetic Mayor Vaughn.

The best performance is left to Robert Shaw, as the crusty, wryly brogued sea dog Quint, as he bullets through the last half of the film with grim, hard-headed, but ultimately reckless bravado. It is the performance of a lifetime. The single most captivating scene in the film is where Robert Shaw narrates the true story of the torpedoing of the USS Indianapolis during WWII and of the survivors helpless in the water being picked off by sharks, a scene that Shaw himself wrote. (Ironically, scenes like this were due to the massive production delays where the crew were sidelined through technical problems and so had little more to do than endlessly rehearse scenes). Robert Shaw should have won the Oscar for the role but instead he was not even nominated and the award went to George Burns for his muchly inferior part in The Sunshine Boys (1975).

There were three sequels – Jaws 2 (1978), Jaws 3-D (1983) and Jaws: The Revenge (1987). Roy Scheider, Murray Hamilton and Lorraine Gary appeared in Jaws 2 and Lorraine Gary in Jaws: The Revenge, even though all of the sequels feature the Brody family. Carl Gottlieb wrote the scripts for Jaws 2 and Jaws 3-D. Jaws: The Untold Story (2010) is a documentary about the making of the film.

Jaws has been spoofed in The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1978), Piranha (1978), Alligator (1980), Blood Beach (1980), Saturday the 14th (1981), Blades (1989) and Trees (2000).

Steven Spielberg’s other genre films as director are:– Duel (1971), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Always (1989), Hook (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001), Minority Report (2002), War of the Worlds (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), The Adventures of Tintin (2011), The BFG (2016) and Ready Player One (2018). Spielberg has also acted as executive producer on numerous films. Spielberg (2017) is a documentary about Spielberg,

Peter Benchley became a best-selling author solely as a result of the Jaws credit. Other films were quickly adapted from Benchley’s work, including the deep-sea treasure hunting film The Deep (1977) and The Island (1980), an interestingly failed film about a lost society descended from pirates. Later Benchley works include the monster mini-series’ The Beast (1996) and Creature (1998) and the tv series Amazon (1999) – in all three of the latter, Peter Benchley’s name appears above the title.

Trailer here