Crew

Director/Screenplay – Michael Mann, Based on the Novel The Keep by F. Paul Wilson, Producers – Gene Kirkwood & Howard W. Koch Jr, Photography – Alex Thomson, Music – Tangerine Dream, Visual Effects – Industrial Light and Magic, Peter Kuran & Wally Veevers, Special Effects Supervisor – Nick Allder, Makeup Effects – Nick Maley, Production Design – John Box. Production Company – Howard W. Koch Jr-Gene Kirkwood.

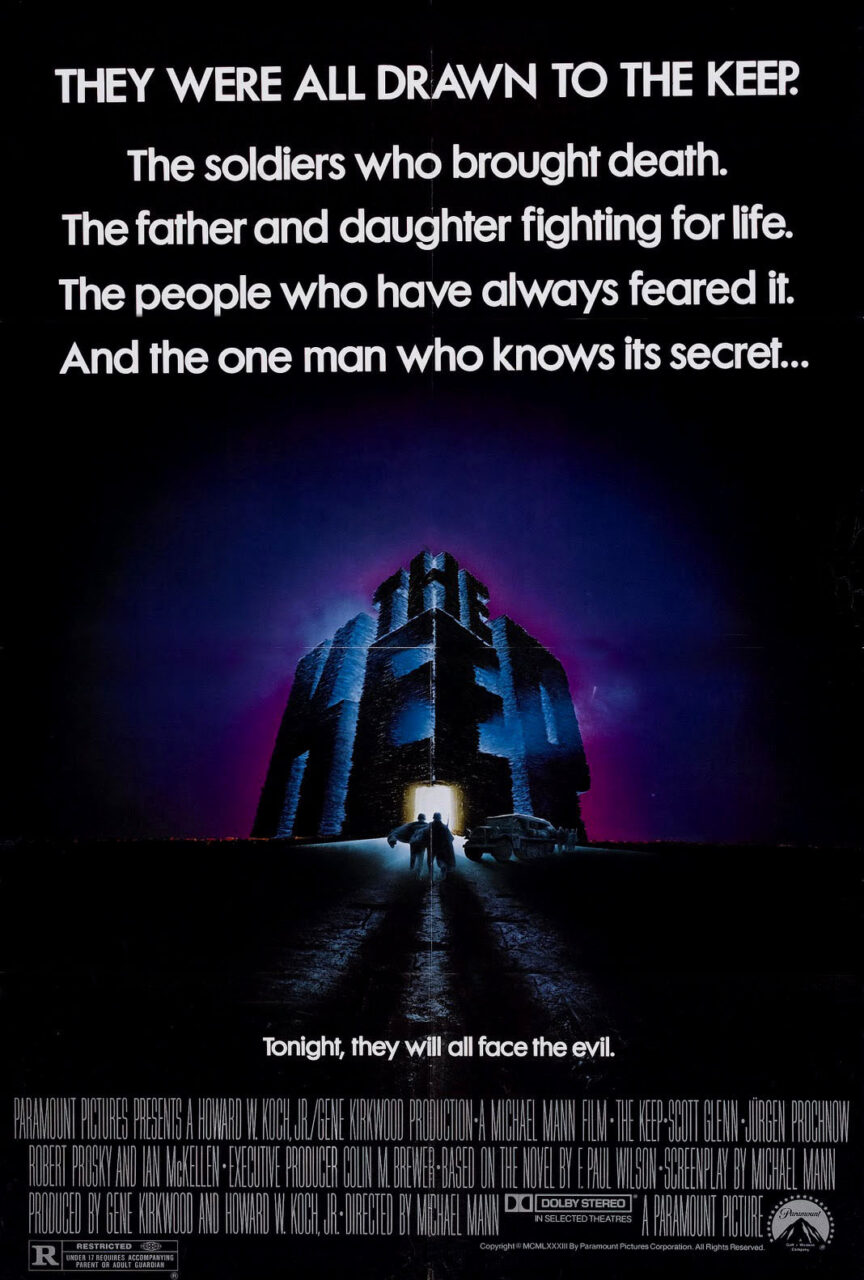

Cast

Alberta Watson (Eva Cuza), Jurgen Prochnow (Captain Klaus Woermann), Scott Glenn (Glaeken Trismegatus), Ian McKellen (Dr Theodore Cuza), Gabriel Byrne (Sturmbahnfuhrer Kaempffer), Robert Prosky (Father Fonescu)

Plot

1943. A detachment of Wehrmacht soldiers takes occupation of a forbidding fortified keep on the Romanian border to guard against possible invasion from the Russian front. The greedy soldiers, thinking the hundreds of tau crosses embedded in the walls are silver, try to prise them out. In so doing, they unwittingly release something buried inside the keep that emerges each night to devour the lives of the men. An SS detachment arrives and to the horror of the humanitarian Wehrmacht captain Woermann begin rounding up and shooting the peasants, believing the killings are partisan activity. Inscriptions in a dead Romanian language are found near the bodies and so the SS reluctantly bring in Jewish linguist Theodore Cuza to translate. The creature in the keep, known as The Molasar, appears to Cuza. It heals the wasting disease that cripples him and asks his help in escaping the keep so that it can wipe out the Nazi evil. Cuza eagerly helps, seeing the possibility of freeing his people from the Nazis. At the same time, the strange immortal Glaeken Trismaegatus appears in the village, asking the help of Cuza’s daughter in destroying the evil of the Molasar.

When The Keep was first announced as a film project, I remember becoming immensely excited and waited in enormous anticipation to see it. Not even the delays in release due to the death of effects man Wally Veevers or the middling reception granted the film when it opened dimmed my enthusiasm. The idea of an immortal monster taking on Nazis – supernatural evil vs human evil – seemed intensely exciting, while the story seemed to promise a fascinating revamping of vampire mythology.

The film is based on a 1981 novel by New Jersey doctor F. Paul Wilson, a minor writer of some passable horror and sf novels. After the book became a best-seller, the film adaptation was taken over by Michael Mann. At the time, Mann had begun working as a writer and later director on 1970s tv cop shows such as Police Story (1973-7), Police Woman (1974-8), Starsky and Hutch (1975-9) and had created the tv series Vega$ (1978-81). Mann made his directorial debut with the worthwhile but little seen Thief/Violent Streets (1981), which defined the cool, moody, Euro-styled crime thriller that Mann has become most associated with.

Subsequent to The Keep, Mann made the first Hannibal Lecter film Manhunter (1986) and then created the quintessential 1980s cop show Miami Vice (1984-9). Miami Vice represented the essence of the Mann style – shot in evocative washes of primary colour, amid often stylised sets set dressed with a bare minimalism, the ambient soulnessness of electronic music (frequently German group Tangerine Dream) on the soundtrack, and the moody quest for interior spaces. Despite the No. 1 hit of Miami Vice, neither The Keep nor Manhunter were successes in theatres and Mann was subsequently stuck in tv land, producing shows like Crime Story (1986-8) and various mini-series.

It was not until the 1990s that Mann returned to the director’s chair with The Last of the Mohicans (1992) and then wowed everybody with Heat (1995) before moving onto his epic canvas true-life dramas and award-friendly favourites such as The Insider (1999), Ali (2001) and Public Enemies (2009) and subsequent crime thrillers like Collateral (2004), Miami Vice (2006) and Blackhat (2015). Michael Mann’s one other genre credit is as a producer of Hancock (2008), which he was once slated to direct.

As a film, The Keep feels torn between two camps. It feels like it is stuck aground unable to find a common place between the stylish arthouse chic of director Michael Mann and the pulp horror elements of F. Paul Wilson’s novel. It is clearly the ideological scope of the novel that attracted Michael Mann, not the horror element. What we end up with is another case of filmmakers with artistic pretensions being afraid of horror – Mann seems only interested in the Molasar as metaphor for Nazi evil and has gone even so far in the film as to divorce any of the implications that The Molasar was a vampire that Wilson gave us in his book.

As a horror film, Michael Mann crucially never digs his teeth into the audience, never evokes any sense of dread during The Molasar’s appearances. There are a couple of frissons to the first attack, and the creature’s rescue of Alberta Watson is genuinely unearthly. However, rather than devouring his victims, all the Molasar does is seem to emerge in laser light effects and mist with glowing red eyes. Certainly, the ideas inherent in F. Paul Wilson’s somewhat pulpish novel find a better airing here than on the page – there is that great moment where the Molasar steps up to Gabriel Byrne’s SS commandant, effortlessly crushing his crucifix, “Where am I from? I am from you.”

If looks alone could make a horror film, then The Keep would be a classic. Michael Mann uses the oppressiveness of white-on-white walls and the dank grey-black of the perpetually mist-layered keep in the same way that an impressionist uses watercolours. The stone and narrow hallway sets are stunning and the way that Mann creeps the camera through in dreamy slow-motion to the metallic tappings of Tangerine Dream’s electronics creates a great deal of atmosphere. Even the love scenes are something ritualised, not of this world. Regrettably the arty pretensions get the better of Michael Mann during the latter half of the film – with the blank-faced Scott Glenn in purple contact lenses and talking as though with a mouthful of marbles, giving the most laughably daft performance of his life. The film arrives at a climax that is pretty but meaningless Spielberg light effects.

It is lamentable that the care Michael Mann languished on the film – he proudly spoke in interviews of how dialogue coaches were obtained to get the regional inflections of each character’s dialogue down pat, and how the WWII military hardware was authentic – could not have been spent on producing less artful and more impact-ful scares. There are fair performances from Jurgen Prochnow, a then unknown Ian McKellen and the beautiful Alberta Watson, but as characters they seem swallowed up by one director’s fascination with mood almost to the exclusion of all else.

F. Paul Wilson (who called the film version ‘incomprehensible’) later expanded the basics of The Keep into a six-volume series of novels. The concept of soldiers facing supernatural evil in a claustrophobic space was later used with much greater horror effect in the British-made The Bunker (2001), The Devil’s Tomb (2009) and the New Zealand film The Devil’s Rock (2011), while the basics were transplanted to World War I with Deathwatch (2002) and Bunker (2022) and amid US soldiers in contemporary Afghanistan in Red Sands (2009).

Trailer here