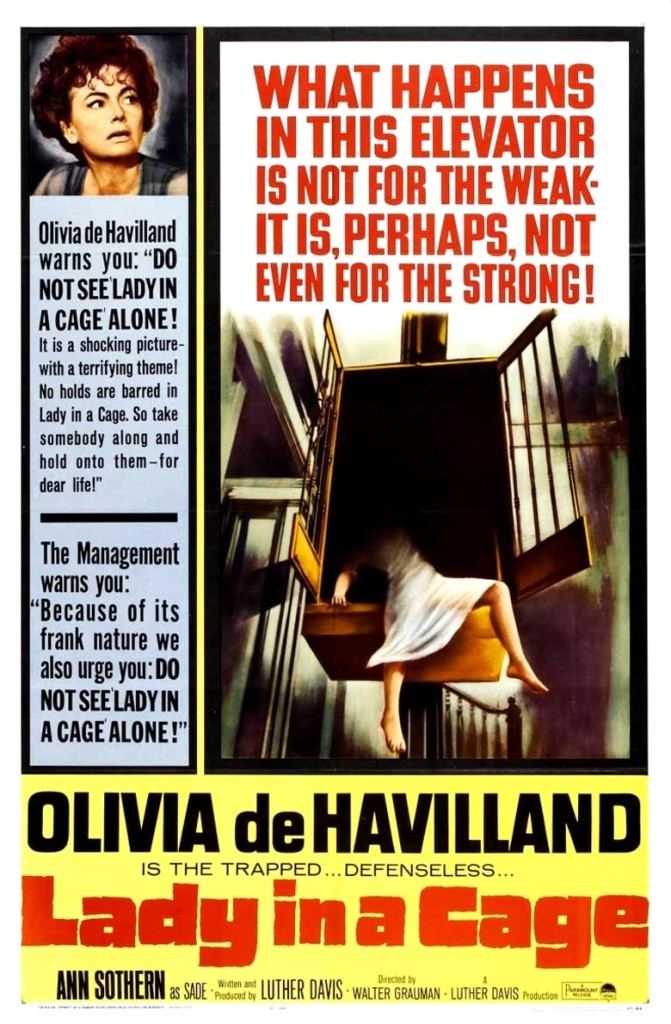

USA. 1964.

Crew

Director – Walter Grauman, Screenplay/Producer – Luther Davis, Photography (b&w) – Lee Garmes, Music – Paul Glass, Photographic Effects – Paul K. Lerpae, Production Design – Rudolph Sternad. Production Company – Luther Davis Productions.

Cast

Olivia De Havilland (Mrs Hilliard), James Caan (Randall O’Connell), Jeff Corey (George L. Brady Jr), Jennifer Billingsley (Elaine), Rafael Campos (Essie), Ann Sothern (Sade), William Swan (Malcolm Hilliard)

Plot

Wealthy Mrs Hilliard is left behind in her home after her son Malcolm goes away for a long weekend. She is recovering from a broken hip and needs an elevator that has been specially installed so that she can travel between floors. However, a workman knocks the power junctions outside her house with his ladder, cutting the power and leaving her trapped between floors in the elevator cage. Alcoholic derelict Randall O’Connell breaks into the house and steals wine and various belongings to hock. However, when Randall returns, he is followed by three petty hoods who revel in trashing the house and torturing Mrs Hilliard as she is imprisoned.

Lady in a Cage is often placed – erroneously so – in the 1960s mini-genre of Batty Old Dames thrillers that began with What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). It has a number of nominal similarities to these films – it features a middle-aged former Hollywood star past her prime cast in a deliberately unglamorous role and taps into this genre’s frequent theme of their home as a world rooted in the past, festering with repressions and a refusal to come to terms with the modern world.

That said, Lady in a Cage belongs in a different category altogether – in fact, it is a prefigural of a host of films that came along a decade later beginning with Straw Dogs (1971) and continuing through the likes of The Last House on the Left (1972), Deliverance (1972), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977), among many others, where a person or a group of people are besieged by violent, unsocialised forces, something that this author has termed the Backwoods Brutality genre.

The besiegement is conducted with considerable effect by director Walter Grauman and the tension maintained at a remarkably high degree. The film essentially consists of a series of rollercoaster peaks, of hopes for Olivia de Havilland’s escape being built up and then crushed – the telephone ringing and she trying to reach it from the elevator cage; she managing to tear off two pieces of metal that she thinks can serve as knives; and the ratcheting of intensity once Grauman puts thug James Caan in the cage with her. Caan in frequent bared chest gives a notable performance of languid, charged sexual aggression.

The film should also be noted for the stark violence it holds – like where James Caan swings a lamp around his head on its cord and bashes Jeff Corey with it, or the knife stabbing that comes conveniently hidden behind a couch, where all we see is the arm and knife repeatedly coming up over the back.

The film captivates from the opening where the credits, clearly influenced by Saul Bass’s distinctive titles for Alfred Hitchcock, come with a remarkable boldness – lines coming down the screen, cars pulling into the frame and the radiator grille or headlights metamorphosing into patterns, even an exploding manhole cover flying through the air, freezing and turning into an animated silhouette graphic.

Most of all though, Lady in a Cage wants to set up a dialectic between the woman of privilege in her literal gilded cage and the world outside her doors, which is seen as a savage and unreasoning place. The opening credits are filled with the image of dozens of cars passing the suburban street where Olivia de Havilland lives, signifying the world beyond her door as a place of haste and uncaring, and a montage of images, including a young Black girl running a rollerskate over the bloodied leg of a man lying on the pavement (we are not sure if he is dead or passed out drunk as the film never returns to the image again).

Like Straw Dogs, The Last House on the Left, Deliverance and Death Weekend/The House By the Lake (1976), Lady in a Cage works on a single premise – the rape of middle-class values, the stripping away of all illusion and the reduction of the middle-classes to a seeming state of barbarism in order to protect themselves from the onslaught of human savagery baying at their door. The attackers here are seen as barbarous and brutal: “You’re one of the offal produced by the welfare state,” Olivia de Havilland remonstrates them with classical conservative disgust at one point. “You’re what my tax money goes to feed.” We are constantly given images of the world’s indifference to Olivia de Havilland’s torture – cuts away to noisy parades, the repeated image of more cars passing down the cosy suburban street than would seem ever possible unless it happened to be a major highway.

Olivia de Havilland also echoes many of the sentiments of the Cold War era when the film was made – the feeling that the imminent collapse of the world was nigh. “The world must’ve ended,” she theorises as she is trapped in her apartment without power. “Someone on one side or another must’ve pushed the button, dropped The Bomb.” Later there is a pullback across the suburban neighbourhood and a voiceover from her comparing the world to a jungle, where animal nature hides behind all civilised pretence.

Naturally, Olivia de Havilland’s only recourse is to herself abandon all civilised pretence herself and become as ruthless as her tormentors – “Stone Age – here I come,” she triumphantly announces. This message is stridently presented, although like the better entries in this savagery cycle, the moral waters are not always clearcut. As much as the film sees middle-class values recoiling in horror at the violence beyond their door, it also portrays the home that is being defended as a place of cloying repression, with Olivia de Havilland’s control over her son being seen as so stifling that it is driving him to suicide.

Director Walter Grauman premiered with the B-budget witch doctor film The Disembodied (1957). He had a modest hit with the war film 633 Squadron (1964), although spent the rest of his career (which stretched between the 1950s and 1990s) working in television. His other noted genre work was the occult tv movie Crowhaven Farm (1970).

Trailer here