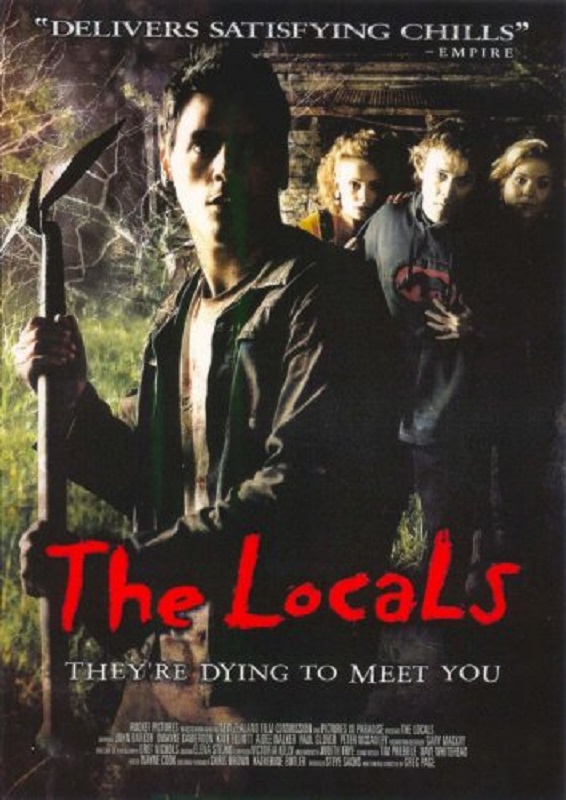

New Zealand. 2003.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Greg Page, Producer – Steve Sachs, Photography – Bret Nichols, Music – Victoria Kelly, Special Effects – Film Effects (Supervisor – Jason Ames), Makeup Supervisor – Deb Watson, Production Design – Grant Mackay. Production Company – Rocket Pictures Ltd/Pictures in Paradise Ltd.

Cast

John Barker (Grant), Dwayne Cameron (Paul), Kate Elliott (Kelly), Aidee Walker (Lisa), Paul Glover (Martin), Peter McCauley (Bill), Glen Levy (Tone), Dave Gibson (Nev)

Plot

Grant is disconsolate following a split-up with his girlfriend. His best friend Paul persuades him to forget about things and come surfing with him for the weekend. They drive south from Auckland down into the Waikato countryside but become lost after taking a short cut. They meet two girls who invite them come to a party but instead end up crashing off the road. Seeking help, they go to a farmhouse, only to see a man slashing a woman’s throat. They are spotted and then pursued by a group of armed locals. As they run for their lives, they find that their pursuers have the disconcerting ability to keep getting up again after they have been killed.

The Locals is a modestly budgeted New Zealand-made horror film. It was the debut of music video and commercials director Greg Page and shot with a cast of unknowns. The Locals seems at the outset to be shaping up to be a Kiwi variant on the Backwoods Brutality cycle of the 1970s, an era that produced films like Straw Dogs (1971), Deliverance (1972), The Last House on the Left (1972), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), The Hills Have Eyes (1977) Day of the Woman/I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and Southern Comfort (1981). All of these films feature city slicker types venturing out into the countryside only to fall afoul of psychotic in-bred locals who harbour a resentment of their more sophisticated ways. New Zealand even produced one Backwoods Brutality variant before with Ian Mune’s largely forgotten Bridge to Nowhere (1986).

Alas, the whole Backwoods Brutality theme sits uneasily in rural New Zealand. You feel that Greg Page is more quoting American models than he is tapping into any resentment between urban sophistication and rural farming types that exists in the country. It does exist but more as a joke that pokes fun at the self-important Auckland metropolitans made by the rest of the country than anything else. Certainly, there is not the almost mythical belief, as you get in American exploitation cinema of the 1970s, that Otago sheep herding country might harbour something akin to psychotic Appalachian hillbillies or that the Manawatu bushland might fester with the equivalent of in-bred Cajuns seeking to hunt down wayward city folk. The 1970s Backwoods Brutality cycle was always about tearing open the placidity of middle-class assumption, the belief that the more one went out into the borderlands of the great American dream, the more that that illusion would fall apart and be rent asunder by the harsh brutality of the real world.

However, the Kiwi zeitgeist seems entirely uncertain whether its sympathies lie with the city clickers or the rural types. New Zealand is a country that has never felt fully comfortable with being metropolitan, in that most of the country is still a generation away from the self-view that it was a cosy English country village. This makes the polarities that the American Backwoods Brutality cycle operates on far less certain.

In New Zealand cinema, the portraits of heroes have tended to hold sympathy with the Man Alone character who is ruggedly self-contained and conversant with the ways of the land but awkward and alienated when it came to issues of the heart and belonging to society – look at films like Smash Palace (1981), Bad Blood (1982) (which was about the rural hero worship that surrounded a real-life mass murderer who defied the government), Utu (1983), Pallet on the Floor (1984), The Quiet Earth (1985) or Vigil (1985), and to some extent The Piano (1993). It is either that or a celebration of yobbo anti-authoritarianism that runs through films like Goodbye Pork Pie (1980) and early Peter Jackson films like Bad Taste (1988). New Zealand for example has never produced anything in the way of a comedy of metropolitan mores.

It is an awkward divide that gets played out in The Locals, which never seems able to muster up much in the way of being able to cast its rural types with the insanely disturbed menace that they come with in films like Texas Chain Saw or Deliverance, yet at the same time fails to grant much in the way of sympathy to its two youthful city slickers, whose repartee and clowning in the establishing scenes is both annoying and self-conscious. (Although, Greg Page does get a good joke off mocking the Kiwi reverence of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy).

The Locals settles in adequately once the suspense starts – Greg Page generates passable tension during the scenes with the two heroes fleeing truckloads of farmers, hiding in meat safes and the like. There are a couple of moments when he almost seems on the verge of discovering a genuine style. For a time, The Locals holds you to it with some of its weirdness in wondering what is going on – like where John Barker is forced at gunpoint by Paul Glover to dig up a grave and discovers a body dressed in the same plaid bush shirt that Glover is, which causes Glover to start uncomfortably twitching when he moves the body; or when the two bogans that are incinerated in their car suddenly turn up alive again. Yet Greg Page never particularly puts the screws on his audience in a way that makes them feel bolted to their seats in the same way that films like Texas Chain Saw or any of the aforementioned Backwoods Brutality classics did.

Eventually, The Locals turns out to not even be a Backwoods Brutality film at all. What the film segues into is sort of a supernatural version of Dead & Buried (1981), which was about a small American town where it gradually became apparent that all the townspeople were zombies. Maybe Dead & Buried with a dash or two of Groundhog Day (1993). Although what The Locals finally reveals itself as is yet another copy of The Sixth Sense (1999). Greg Page has set the film up to conduct the same sort of conceptual reversal that M. Night Shyamalan did in The Sixth Sense – of directing one to think in one particular direction and then pulling a surprise reversal to reveal that the central character was dead.

Alas, this is where The Locals falls apart. In the few years after The Sixth Sense, the whole people-turning-out-to-really-be-dead thing started to become a passé and overused surprise. Greg Page fails to manage his twists well enough for it to be a big, big surprise. He has fallen into sequel-type thinking that providing more of something that was successful the first time equates with better – here it is not just one character on screen that turns out to be dead, but every single character except one.

Moreover, Greg Page fails to explain everything that well. The milieu the story takes place in exists in a vacuum – we never find out why this particular part of the countryside (as opposed to any other) causes the dead to return to life. It would not have taken much at all for the film to have thrown in a nominal explanation about the area being tapu land or some such. There are all sorts of rules that life there seems to operate by – it is of some importance to carry the bones of the dead beyond the river (although we never find out why), the living must leave before dawn, damaging the original bones somehow affects the resurrected body – but again none of these come with any rationale outside of the arbitrariness of the decision to include them. All that that makes is a film with a novelty gimmick and an initially interesting set up that has failed to sit down and do any thinking about how to explain such a premise.

Trailer here