USA. 1976.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – George A. Romero, Producer – Richard Rubinstein, Photography (colour and some scenes b&w) – Michael Gornick, Music – Donald Rubinstein, Special Effects/Makeup – Tom Savini. Production Company – Braddock/Laurel.

Cast

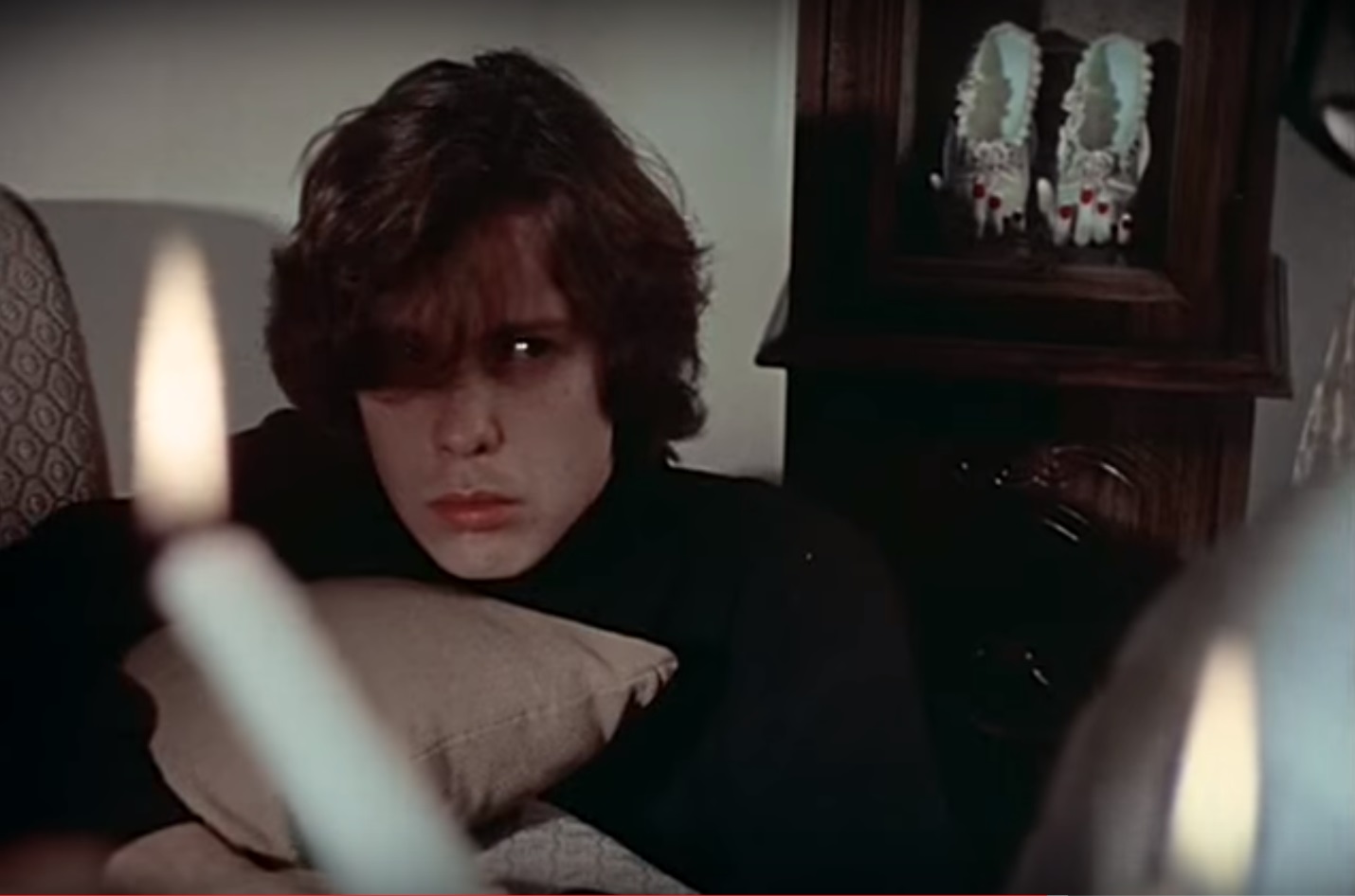

John Amplas (Martin Matthias), Lincoln Maazel (Tati Cuda), Christine Forrest (Christina), Elyane Nadeau (Mrs Santini), Sarah Venable (Housewife Victim), Al Levitsky (Lewis), George A. Romero (Father Howard), Fran Middleton (Train Victim), Tom Savini (Arthur)

Plot

Martin Matthias arrives in Pittsburgh to stay with his uncle Tati Cuda. Cuda is steeped in the superstitions of the old country and is certain that Martin, though seemingly only a teenager, is in fact an 84-year-old vampire. Martin is contemptuous of Cuda and insists that none of the superstitions work. At the same time, Martin has a compulsive need to go out, drug women and drink their blood.

The single image that is unalterably associated with the vampire to this day is that of Bela Lugosi is a dinner-suit and cape, leering with hammy menace and proclaiming “I neffer drink vine” in thick European accent. It is an image that entirely dominates the vampire film, is associated with it even by those who have never seen the Bela Lugosi version of Dracula (1931), is the basis for umpteen bad parodies and at least for one person to come outfitted as to every fancy dress party. For all the influence it has though, the 1931 Dracula is not a particularly good film and Bela Lugosi one of the worst actors to ever work in the horror genre. However, for the next quarter of a century, the vampire film took its lead from Lugosi – all vampires were becaped and thickly accented foreign menaces.

It did not take long for Universal’s monster team-ups of the 1940s to turn the Lugosi vampire into a cardboard cutout and it took Hammer’s remake Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958) to revitalise the vampire. Here the vampire emerged for the first time in colour and Christopher Lee’s performance gave the vampire a raw, animal charge, bringing out all the inherent sexuality that Lugosi had lacked. However, each generation’s revivals, as they are wont to do, eventually become trapped in their own creative dead-end and by the 1970s the Hammer vampire film had petered out into puerile softcore erotica and a series of tired Dracula sequels that seemed to find increasingly little for Christopher Lee to do.

By the mid-1970s, the vampire film had reached a creative dead end. The traditional image of the vampire in cape and period surroundings had been milked for all it could be. Various attempts to update the vampire – Hammer’s Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972) and The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973), Count Yorga, Vampire (1970), the tv series Dark Shadows (1966-70), the tv movie Vampire (1979) – only ended up transposing the figure into the present cape and all and in so doing made it more than clear that the traditional vampire was an anachronism. Dracula A.D. 1972 set Christopher Lee’s Dracula absurdly at odds with Swinging London and all Dark Shadows did was to confine its vampire to a vast Gothic mansion that might as well have been period.

By the late 70s/early 80s, all that could be found of the classic image of the vampire was in comedies such as Vampira/Old Dracula (1974), Tender Dracula (1974), Dracula, Father and Son (1976), Love at First Bite (1979), Mama Dracula (1980), Once Bitten (1985) and the ultimate indignity, the porn film Dracula Sucks (1979). The only efforts, until Martin came along, that tried to come to grips with updating the habits and behaviour of the vampire for the modern world were The Velvet Vampire (1971) and in particular the tv movie The Night Stalker (1972). Later films such as Salem’s Lot (1979), Fright Night (1985), Near Dark (1987), Nadja (1994), The Addiction (1995), Blade (1998), Ultraviolet (1998) and Vampires (1998) would be more successful at relocating the vampire film into the modern world.

In 1976 came Martin, which attempted what is the most potent cinematic deconstruction of the vampire myth to date. Martin is a remarkable film. It dismisses all the mythological elements of vampirism. The vampire in Martin has no supernatural powers. It is able to go out in daytime. It lacks the raw animal magnetism of its cinematic forebears – it even gets an amusing speech bemoaning its lack of mind control abilities or any of the seductive powers of its cinematic counterparts. Martin, the vampire, appears as a weak, slightly autistic teenager – he is a pitiable creature who owes its ancestry more, if anything, to Norman Bates than Bela Lugosi. Any sense of Martin being evil exists only in the minds of the vampire hunters.

On the opposing side, the requisite Van Helsing type is played as a close-minded religious extremist. A Catholic priest (played by director George A. Romero himself) turns up but is more interested in social services than spiritual issues; in fact, the priest appears somewhat perplexed when the vampire hunter raises the topic of metaphysics, although does at least offer an appreciation of The Exorcist (1973).

In fact, the question of whether Martin actually is a vampire or not is left ambiguous. Like the unjustly neglected Incense for the Damned/Bloodsuckers (1969), Martin makes the point that a vampire could just as easily be a sexually dysfunctional individual with a blood fixation. Or equally that Martin could simply believe he is a vampire because of the family’s oppressive religious fixations. The film never does confirm for us whether Martin is a vampire or is just mentally ill, which surely makes Martin the first existential vampire movie.

Director/screenwriter George Romero makes all manner of striking contrasts. He deliberately juxtaposes cliches of B-movie vampirism with modern-day realities. In one striking scene, Martin plays a prank on Tati Cuda the religious extremist, stalking him in an alley, dressed in cape, white-face and joke-store fangs, and then pulls the costume off to laugh in his face. Black-and-white period scenes that could have been taken out of any classic vampire film are vividly placed alongside modern more unromanticised visions – the seduction of a woman in her boudoir is contrasted with a modern scene where Martin has to drug his female victim; scenes of villagers with burning torches are contrasted with a cop car chase. There is not inconsiderable humour in some of the scenes where the myth is placed alongside contemporary incongruities – throughout the film Martin calls up a radio talkback show to speak about his problems as a vampire where he is promptly referred to as The Count. Indeed, it comes as a surprise to see a vampire film that is located in the poorer areas of Pittsburgh simply for the fact that prior to this we had rarely seen a vampire film set in the real world.

On the minus side, the pace of Martin is slow moving. The score is dull. At one point, George Romero seems to feel the need to throw in a car chase in order to spice the proceedings up but it feels out of place. However, the individual set-pieces in between are genuinely striking. Particularly memorable is the opening where Martin drugs the woman on the train then slits her wrists to drink from her, all the while promising that he will be gentle, even trying to wrap her limp arms around him in the affectation of a caress. Also highly amusing is the scene where Martin invades the home of a housewife he has carefully stalked only to find her in bed with another man, whereupon things start to go disastrously wrong.

Taste the Blood of Martin (2023) is a documentary about the making of Martin.

Martin came from George A. Romero who a few years earlier had set the world alight with his cult favourite Night of the Living Dead (1968). Throughout the 1970s, Romero maintained a presence as an independent director but never easily found the same success as Night of the Living Dead again. He made other genre films such as the suburban witchcraft film Jack’s Wife/Season of the Witch/Hungry Wives (1972) and the excellent but unsuccesful The Crazies (1973) about a madness-inducing germ warfare spill. Martin was highly acclaimed by almost all who see it but has suffered from spotty cinematic and video distribution, although is a film that is as much deserving of cult success as Night of the Living Dead was. It took Romero’s Night of the Living Dead sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978), for him to fully emerge as a name again.

George Romero’s other genre films are:– the Stephen King-scripted horror comic homage Creepshow (1982); Day of the Dead (1985); Monkey Shines (1988) about a psychic link between a paraplegic and a murderous monkey; Two Evil Eyes (1990), an Edgar Allan Poe collaboration with Dario Argento; The Dark Half (1993), from the Stephen King novel about a writer haunted by an evil doppelganger; Bruiser (2000) about a man whose face suddenly becomes a blank mask; Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2007) and Survival of the Dead (2009). Romero has also produced the Tales from the Darkside (1983-5) and Monsters (1988-9) horror anthology series, as well as the films Deadtime Stories (2009), Deadtime Stories 2 (2010) and the remake of The Crazies (2010). His scripts include Creepshow II (1987), Tales from the Darkside: The Movie His scripts include Creepshow II (1987), Tales from the Darkside: The Movie (1990) and the remake of Night of the Living Dead (1990). Also of interest is George A. Romero’s Resident Evil (2025), a documentary about Romero’s unmade Resident Evil film. The making of Martin is also briefly covered in the Romero documentary Document of the Dead (1989).

Trailer here