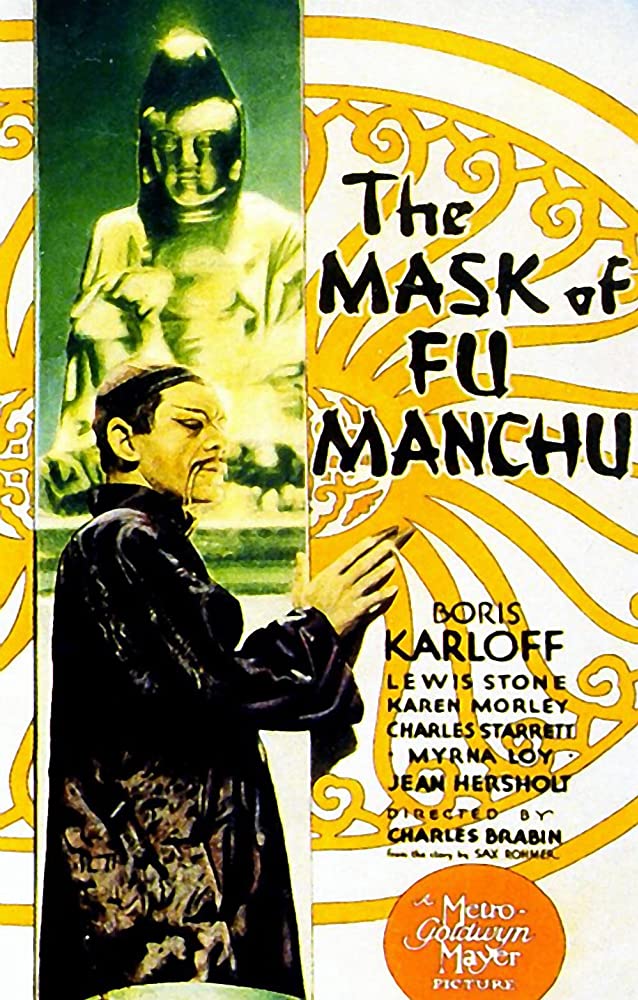

USA. 1932.

Crew

Director – Charles Brabin, Screenplay – Irene Kuhn, John Willard & Edgar Allen Woolf, Based on the Novel The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) by Sax Rohmer, Photography (b&w) – Tony Gaudio, Special Electrical Effects – Kenneth Strickfaden, Art Direction – Cedric Gibbons. Production Company – Cosmpolitan/MGM.

Cast

Boris Karloff (Dr Fu Manchu), Charles Starrett (Terrence Granville), Lewis Stone (Nayland Smith), Karen Morley (Sheila Barton), Myrna Loy (Fah Lo See), Jean Hersholt (Professor Von Berg), Lawrence Grant (Sir Lionel Barton)

Plot

Sir Lionel Barton leads a British expedition to Mongolia to find the Golden Death Mask and Scimitar of Genghis Khan. They are in a race to find the artifacts before the Chinese criminal genius Fu Manchu who wants the relics in order to unite the armies of Asia under him. They are successful in locating the tomb but Fu Manchu then captures the members of the expedition and subjects them to perverse tortures to make them divulge the whereabouts of the artifacts.

Sax Rohmer (real name Arthur Henry Ward) (1883-1959) had an incredible popularity with his Fu Manchu stories – 14 novels and story collections published between 1913 and 1959. (If anything, the stories were more popular in America than they were in Ward’s native Britain). There were several entire magazines, The Mysterious Wu Fang and Dr Yen Sing, that attempted to emulate the Fu Manchu character. Outside of the Fu Manchu novels, Ward/Rohmer mined the Asian Peril theme in several other series of books.

A number of Fu Manchu films were spun out in the silent and early sound era, reaching a peak with this the only sound Fu Manchu film made in Hollywood, aside from a serial (The Drums of Fu Manchu (1940). The series was given a new popularity in the 1960s with the series of films starring Christopher Lee beginning with The Face of Fu Manchu (1965). (See below for the other Fu Manchu films).

American adventure films of the 1930s, particularly the serials, always had an incredible jingoism. The very popularity of the Fu Manchu character and Yellow Peril genre reveals an incredible racism bubbling away not far beneath the surface (similar fears also exist in the original Buck Rogers stories). The dialogue here boils its pot with some truly incredible bigotry – “Do you suppose for a moment that Fu Manchu doesn’t know we have a beautiful white girl with us?” Nayland Smith states. Later when Fu Manchu does gets his hands on said white girl she spits out, with the most emotion she has so far demonstrated, “You hideous yellow monster.”

Behind The Mask of Fu Manchu lies the incredible fear that a charismatic leader will rise up to lead the Asian masses to war. Although somewhat subdued in this American-made version (which fails to convince us that its cast are British), the film is underscored with the assumption that ran throughout Sax Rohmer’s books that the British Empire’s rightful place is as arbiter of morality of such heathen nations and it has the unquestionable right to take national treasures that are not unreasonably wanted back by the nation they belong to.

This racism is perhaps not unreasonable in light of the sheer malevolence of Boris Karloff’s performance and the amazing degree of cruelty that is built up around the character of Fu Manchu. Director Charles Brabin shoots Karloff for maximum malevolent effect – he is first introduced through a distorting mirror (which is obviously designed to distort the ‘evil’ occidental makeup) and between flickering Van Der Graaf poles. Boris Karloff plays to the hilt with a wicked smile that seems to take obscene delights in the tortures he inflicts on his victims, balanced out against a subservient, perfectly mannered Hollywood cliche Chinese accent. It is a marked contrast to the definitive Fu Manchu offered by Christopher Lee over thirty years later – Karloff’s Fu Manchu is lascivious, Lee’s coldly aloof. (This film’s Nayland Smith – for some reason minus the Dennis and using Nayland as his Christian name – is aging and anonymous, in no way holding a candle to the decisive Sherlock Holmes-ian man of action in the books or Christopher Lee films).

The Mask of Fu Manchu is almost entirely set around its torture sequences. These are a series of truly amazing set-pieces – one victim is tied upside-down inside a huge bell and tortured by dangling grapes over his lips and splashing salt water over him; another is placed on a bed precariously suspended over a pit of crocodiles with a sand-timer that slowly causes it to overbalance; another between a giant clamp-like device with two spiked pads being wound towards him; and hero Charles Starrett is tied up and injected with serum extracted from spiders.

In the scenes involving Myrna Loy, the torture sequences gain an amazingly festishistic undertow of S&M. She is seen to be voyeuristically looking on and clearly enjoying it as Charles Starrett is taken away, stripped to the waist and beaten, after which she takes him for some comfort in a bed. “He is not unhandsome, my father,” she tells Boris Karloff. Myrna Loy does not quite have the acting ability to suggest the pleasures taken in this but the scenes nevertheless have a clear fascination with the intent.

Charles Brabin was a regular director of the silent era and on into the talkies. His greatest fame was probably as the husband of silent movie star Theda Bara. His one other genre film was the silent Edgar Allan Poe biopic The Raven (1915). Brabin’s major failing is that he is not an action director. The film is static and talky and Brabin fails to milk the torture and action sequences for any suspense, instead sitting the camera at a safe distance and allowing the action to take place within its purview. The film virtually cries out for a modern action director.

As it is, the thrills have a marvellous exoticism. Nayland Smith’s search for Fu Manchu’s hideout, which takes him into an opium den, a cafe with an authentic Chinese opera singer, through a trapdoor underneath a statue in a temple and into a pit of snakes where Fu Manchu waits, is fabulous. So too is the climax with the fetishistic image of heroine Karen Morley tied up as the ‘hideous yellow monster’ prepares to sacrifice her, being saved as Lewis Stone and Charles Starrett ruthlessly turn Fu Manchu’s raygun on the crowds.

Some of the sets are fantastic – entire wall-size maps in the museum, the tomb interior filled with opulent costumery, a bed built into a circular hole in the wall. It is a wonderfully exciting film, one that comes from a lost era of thrills that were operating at the height of its art.

The other Fu Manchu films include:– a series of 23 short silent British films made between 1923 and 1924 starring H. Agar Lyons as Fu Manchu, all of which appear to be lost today; three early sound films from Paramount, The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929), The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930) and Daughter of the Dragon (1931), starring Warner Oland who later gained fame as Charlie Chan; a fifteen chapter serial The Drums of Fu Manchu (1940) from Republic starring Henry Brandon; the tv series The Adventures of Fu Manchu (1956), which only lasted for eleven episodes, starring Glen Gordon; the series starring Christopher Lee produced by Harry Alan Towers, which consisted of The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966), The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967), The Blood of Fu Manchu/Kiss and Kill (1968) and The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969); and The Fiendish Plot of Dr Fu Manchu (1980), a parody of the genre that featured Peter Sellers in his last performance playing both Fu Manchu and Nayland Smith.

Trailer here