aka Curse of the Demon

UK. 1957.

Crew

Director – Jacques Tourneur, Screenplay – Charles Bennett & Hal E. Chester, Based on the Short Story Casting the Runes (1911) by Montague R. James, Producer – Hal E. Chester, Photography (b&w) – Ted Scaife, Music – Clifton Parker, Music Conductor – Muir Mathieson, Special Effects Photography – S.D. Onions, Special Effects – George Blackwell & Wally Veevers, Production Design – Ken Adam. Production Company – Sabre/Columbia.

Cast

Dana Andrews (Dr John Holden), Peggy Cummins (Joanna Harrington), Niall MacGinnis (Dr Julian Karswell), Athene Sayler (Mrs Karswell), Liam Redmond (Professor Mark O’Brien), Maurice Denham (Professor Henry Harrington)

Plot

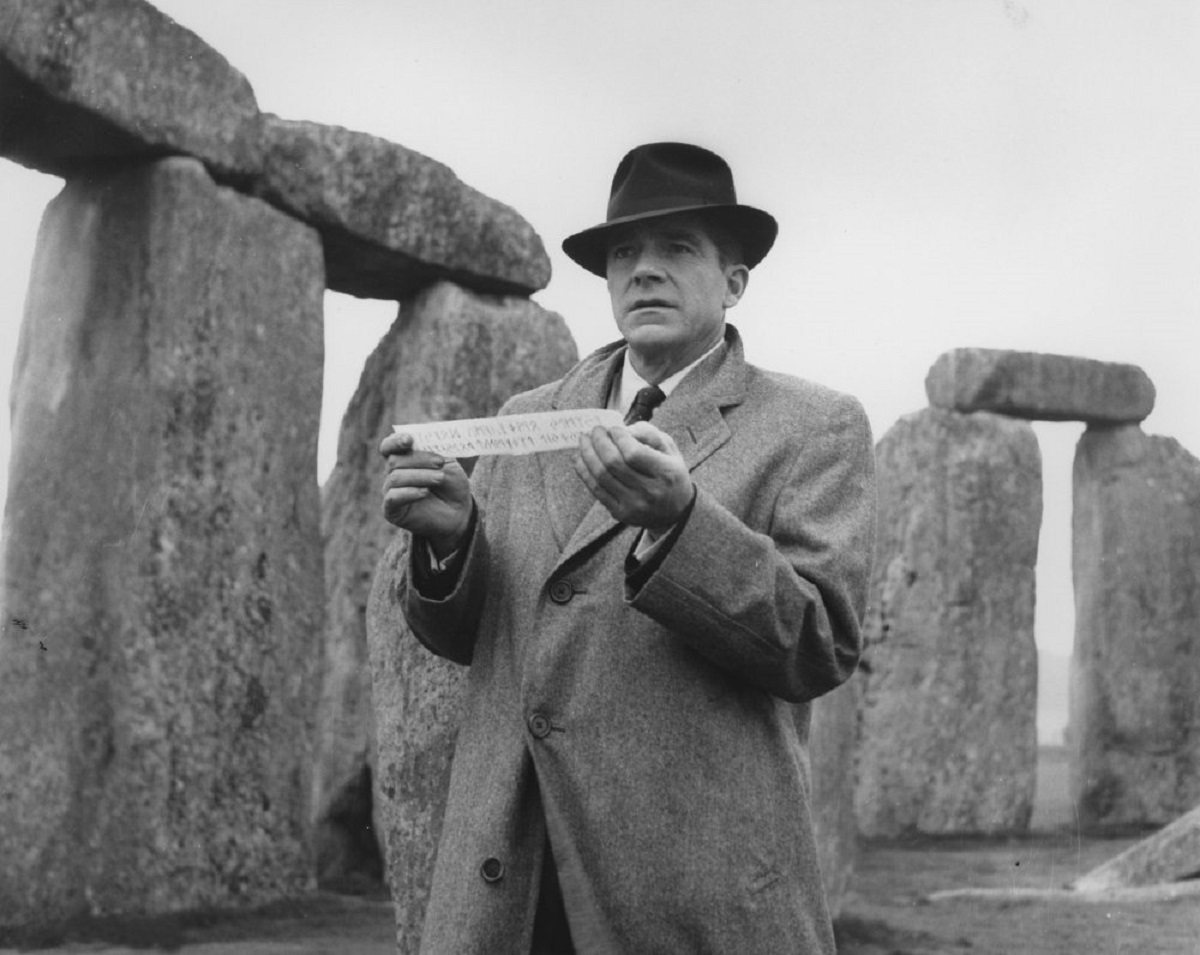

American psychologist John Holden, a determined sceptic of the paranormal, arrives in London for a conference only to find that his colleague Professor Henry Harrington is dead. Some of Harrington’s friends believe that Harrington had a demonic curse placed on him because he was attempting to expose Satanist Julian Karswell, but Holden dismisses the notion. However, as Holden encounters Karswell, he experiences a series of frightening phenomena that leave him uncertain whether they are real or just in his imagination. Holden then discovers that Karswell has passed him a piece of paper that contains a runic curse that will bring about his death in three days time unless he can pass the piece of paper onto someone else.

Night of the Demon/Curse of the Demon is regarded as one of the genuine classics of the horror genre. It is not hard to see why – it is a perfect example of the maxim about the best horror being understated and occurring more in the mind than by depiction. The film’s director Jacques Tourneur made two of the finest films – Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943) – for producer Val Lewton who patented this brand of ambiguous psychological horror.

Night of the Demon has an enormous subtlety to its horror. The film sets up a familiar story about a man of reason forced to acknowledge the existence of the supernatural. (It even at one point throws in then trendy speculations about UFOs and reincarnation in effect to pit reason against the whole of fringe science). Jacques Tourneur bends the film cleverly – the normal daylight scenes, which are equated with reason, are directed with a monotonic flatness as though Tourneur had only the most rudimentary interest in them. However, this proves to be a subtle ploy as Tourneur is lulling us into a false sense of relaxation for when the night-set scenes of the supernatural come, the film becomes edgy – the eruptions of the supernatural are seen only momentarily and the camera lens becomes distorted as though the film itself were undergoing the hero’s journey from rationalism into panicky emotion.

There are many beautifully directed scenes in the film that hover with a sense of unease where one is uncertain whether what is happening is being generated in the mind of the scared hero or not – like Dana Andrews’ entrance into Karswell’s mansion where movement through the house is several times momentarily intercut with a hand on the banister or a door opening and a brief jangling of the score, and the scene in the study where Andrews thinks he is fighting a panther, which only turns out to be a cat; and his pursuit through the woods by invisible footprints and a glowing cloud.

The finest scene in the film is the climax. The psychological battle between Dana Andrews and Niall MacGinnis in the train carriage with Andrews trying to pass MacGinnis objects containing the rune and MacGinnis politely refusing them, neither saying what the other knows, is great. The final moment when the police arrive and Dana Andrews succeeds in passing MacGinnis the parchment is joyous indeed. The image of Niall MacGinnis running along the railway track, trying to catch the parchment as it blows away is one that stays with you – there are fewer images in cinema that seem to so potently portray a doomed and futile desperation. The final image of the demon riding in a wreath of smoke on top of the train carriage is an extraordinary one.

Talk of the demon does bring us to the greatest controversy that surrounds Night of the Demon and that no review of the film ever leaves unmentioned. There has been considerable contention as to whether the demon was added by producer Hal E. Chester in post-production, thinking the public would be unable to handle Tourneur’s Lewtonian ambiguity that left the audience unsure whether the demon was real or not. Revisionists have offered substantial counter-argument based on interviews that Tourneur placed the demon there all along and this would appear to be the case.

The latter assertion is one that one cannot help but have some sneaking affinity for, in thinking that the argument is something that has been more or less invented by the ardent proponents of the less-is-more theorem of horror. The film works perfectly well with the demon – its emergence out of the boiling cloud is genuinely eerie and its appearance on the front of the train is a truly unworldly image. It would certainly be a strange film without the demon, but not as ambiguously Lewtonian as the less-is-more proponents seem to champion the film as being – the argument in favour of the supernatural explanation is so heavily weighed against Dana Andrews that a purely materialistic, sceptical interpretation of the events would be a difficult one to make indeed.

One other area in which Jacques Tourneur does very well is his deliberate undermining of the scenes of the supernatural with the use of humour. The Satanic goings-on are frequently underplayed by a perfectly English ordinariness – the seance is undercut by an extremely funny scene where the two women start (very badly) singing hymns to create mood.

Niall MacGinnis gives a great performance as Karswell (although against the stolid Dana Andrews and the primly repressed Peggy Cummins there is not much competition). He plays Karswell very much against type – and one must remember that at that point the cinema has yet to establish the Satanist as a sinister cliche in symbol-emblazoned robes – as a jolly, friendly and initially unthreatening character. Upon trying to create a wind as a demonstration of his powers to Dana Andrews, he instead conjures an entire storm where his response is not crowing pride but “Oh, dear, I didn’t realise the winds were so strong.” This might possibly be one of the most sympathetic portraits of a Satanist ever put on screen – the scene where he tells his mother he does what he has to out of fear gives an extraordinary insight into the character.

The plot is one of the areas where the film lacks – other entries in this British occult subgenre such as Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn (1961) and The Devil Rides Out (1968) do far better in this regard. The script spins the Montague R. James fragment out to feature length and the most imaginative stretches, particularly the ending, are James, but other parts are clearly padded. Most obvious is the use of Mrs Karswell as a far too convenient tool to push the plot along when necessary – convening seances and passing on vital information about Karswell at various points.

The 1911 M.R. James short story that Night of the Demon is based on was later remade as the tv movie Casting the Runes (1979). It is a great surprise that in this current remake-obsessed era that nobody has attempted a full theatrical remake of Night of the Demon – although in other ways it is not that surprising as one suspects that the era of subtle, ambiguous psychological thrills has long passed. Sam Raimi’s Drag Me to Hell (2009) does however pay homage to several scenes.

Jacques Tourneur’s other films of genre note are:- the Val Lewton films Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943) and The Leopard Man (1943); the Roger Corman black comedy The Comedy of Terrors (1963); and the lost world film The City Under the Sea/War-Gods of the Deep (1965).

Trailer here