aka Nosferatu: a Symphony of Terror; The Twelfth Hour

(Nosferatu – Eine Symphonie des Grauens)

Germany. 1922.

Crew

Director – Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Screenplay – Henrik Galeen, Based [uncreditedly] on the Novel Dracula by Bram Stoker, Photography (b&w) – Gunter Krampf & Arno Wagner, Art Direction – Albin Grau. Production Company – Prana Film

Cast

Max Schreck (Graf Orlok), Gustav von Waggenheim (Johannes Hutter), Greta Schroeder-Matray (Ellen Hutter), Alexander Granach (Knock), Joh Gottowt (Professor Bulwer)

Plot

1838 in the peaceful German town of Bremen. Real-estate agent Johannes Hutter is asked to travel to Transylvania to sell a property to Count Graf Orlok. Leaving his wife Ellen, Johannes travels through the haunted Carpathian mountains to the castle of the rat-like Orlok. Once there, Orlok makes Johannes his prisoner and drinks his blood. As Orlok departs for Bremen aboard the ship Demeter, Johannes tries to make an escape and return to save Ellen before she falls under Orlok’s influence and the town is overcome by his plague.

Nosferatu is possibly the most amazing of all vampire films. This is so for several reasons. It is not simply because Nosferatu was the very first vampire film. Nor is it because it survives today despite a lawsuit by Bram Stoker’s widow over its uncredited and outright theft of the plot of Dracula (1897), a suit that ended with an order for all prints of the film to be destroyed. (Luckily for us they weren’t). Nosferatu amazes most of all because it was – at least until Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) – the most cinematic of all vampire films.

Nosferatu is a surprisingly faithful adaptation of Dracula (or at least of the first quarter of Dracula). Unlike any other adaptation of the novel, more than two-thirds of the story is taken up by the journey to Transylvania. It is the way that director F.W. Murnau launches into the story that takes one’s breath away. The horrors in the book are about something emerging from the repressions of British rationalism. On the other hand, F.W. Murnau creates a film that gives the sense that it has wholly abandoned rationalism and entered into the world of a dark, inverted fairytale.

Murnau drops some of Bram Stoker’s wilder visions from the Transylvania section – Jonathan’s seduction by Dracula’s wives, the image of Dracula crawling down the wall – but his own images are remarkable and his Transylvanian sequences have a far more eerie sense of the otherworldly than Stoker achieved. There is the visit to an inn whose inhabitants are steeped in peasant superstition, while outside a prowling wolf scares horses away. When the coach drops Johannes at the bridge, the driver eerily warns “beyond lies the Land of Phantoms”. The sense of crossing the bridge has the feeling of leaving one world for another, a fact confirmed moments later by the appearance of the black coach where even the rider and horse come swaddled in black.

The most striking feature of Nosferatu is Dracula/Orlok, played by Max Schreck in a fascinatingly crepuscular performance – made up with a rat-like face with bald head, protruding ears, exaggerated eyebrows, two protruding front teeth and a spindly gait where Schreck wears a long black mandarin coat and keeps his arms and long fingernails hunched in front of him by his side. F.W. Murnau accompanies Max Schreck’s appearance with a wild bag of fantastic tricks – doors opening of their own accord, ownerless shadows creeping up stairways and opening doors, the intensely weird image of Schreck rising from his coffin straight as a board and creepy title cards like [in reference to a miniature of Ellen]: “Is this your wife? What a pretty throat.”

Classically, Bram Stoker associated the vampire with a sense of sexual repression that lurked beneath the outward manneredness of Victorian propriety. In Nosferatu, the imagery focuses on death rather than seduction. Dracula/Orlok appears surrounded by rats and even looks like one himself, while his arrival in Bremen is as though he were the Black Plague. The nearest Nosferatu gets to Stoker’s metaphors is the contrast made between the dark blight that Dracula represents and the peaceful innocence of Bremen and Ellen/Mina – but this harkens more back to a purer, more fairy-tale like form of seduction. The film is richly aswim in metaphors – contrasts between Renfield and a Venus Flytrap; between a polyp and Orlok: “transparent, without substance, almost a phantom.” F.W. Murnau achieves much through striking crosscuts – between the earlier scenes with Johannes as Orlok’s victim and Ellen sleepwalking and between Orlok’s voyage aboard the Demeter, between Johannes’s return home and the waiting Ellen and the imprisoned Knock. The ending where Ellen traps Orlok by her bedside, allowing him to feed on her throat until he forgets the coming of daylight and fades away with the sunrise, is nothing short of visually stunning.

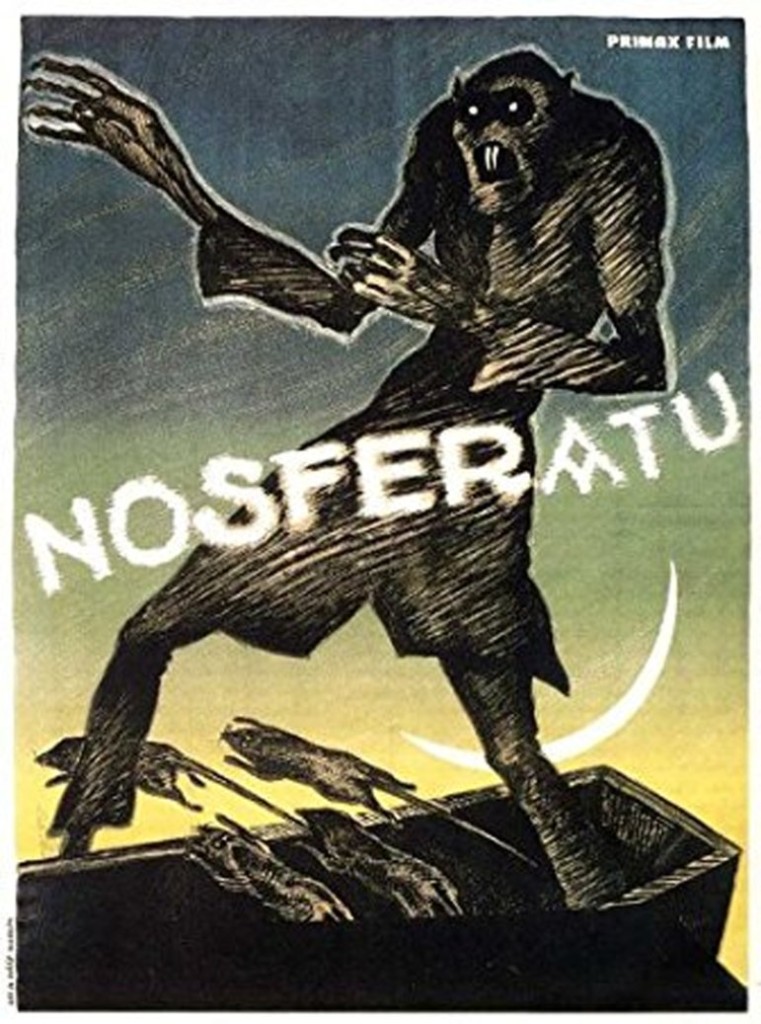

Much of the creative force behind Nosferatu was from Albin Grau. Grau was a devotee of the occult and formed Prana Films with the intent of making works devoted to the occult. Grau produced and was responsible for the film’s conception, costume and production design and poster art. Unfortunately, Nosferatu would be the only film Prana would ever produce and the company was forced to declare bankruptcy following the copyright lawsuit from Florence Stoker, which dragged on for eight years. Grau was involved in the conception and design of one other horror film with Warning Shadows (1924) and design for a couple of other films.

The version of the film seen here is the 1992 print, which annoyingly drops the new names given the characters over the book and renames them after their counterparts in Dracula – Dracula, Harker, Van Helsing and so on. However, it then has the ineptitude to misspell half of them anyway – Jonathon Harker, who now has a wife Nina instead of Mina.

Nosferatu was remade by Werner Herzog as the interesting Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), starring Klaus Kinski as Orlok, who was now legitimately able to be called Dracula because Stoker’s Dracula was out of copyright, and by Robert Eggers as Nosferatu (2024) with Bill Skarsgård as Count Orlok. Over the years, much mythology has built up around the film, most notably the (untrue) claim that Max Schreck (whose surname means ‘fright’ in German) was a mysterious figure about whom nothing is known and who never appeared in any other films again. In fact, Schreck is reasonably well-biographed and appeared in at least a dozen other films. This myth led to the basis of the film Shadow of the Vampire (2000), which is set around the making of Nosferatu and posits that Max Schreck (played by Willem Dafoe) was a real vampire. While a work of total fiction, this is nevertheless an excellent film in its own right.

Both Shreck (1990) and Son of Darkness: To Die For II (1991) are vampire films that names their vampire Max Schreck. Batman Returns (1992) and Final Destination (2000) respectively feature a villain and an FBI agent named Max Schreck; while in Targets (1968), Boris Karloff plays an aging horror actor named Byron Orlock; and the vampire films Transylvania Twist (1989), The Breed (2001) and Dracula 3000 (2004) feature vampires named Orlock. The rat-like look of the vampire has been used in several other films such as Salem’s Lot (1979), Vamp (1986), Black Water Vampire (2014) and What We Do in the Shadows (2014), while a lookalike named Nosferatu appears in Spongebob Squarepants (1999- ). Waxwork II: Lost in Time (1992) contains a brief homage to Nosferatu, while he also makes a cameo in The Haunted World of El Superbeasto (2009) and The Munsters (2022). Nosferatu was edited with bad movie footage and a comedy soundtrack in Nosferatu vs Father Pipecock & Sister Funk (2014), while Mimesis: Nosferatu (2018) is set among a present-day recreation.

F.W. (Friedrich Wilhelm) Murnau made several other horror films in Germany including Der Januskopf (1920), a lost adaptation of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde; the old dark house film The Haunted Castle (1921); and the fabulous Faust (1926). Murnau next emigrated to the US where he made Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), which is considered one of the greatest of all silent films.

Other adaptations of Dracula are:– Dracula (1931) with Bela Lugosi; the Spanish language version Dracula (1931) shot on the same sets as the Lugosi version starring Carlos Villarias; Hammer’s classic Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958) with Christopher Lee; Dracula in Pakistan (1967), an uncredited remake of the Hammer film; Count Dracula (1970), Jess Franco’s version also with Lee; Dracula (1974), the Dan Curtis tv movie starring Jack Palance that was released to cinemas, Count Dracula (1977), the BBC mini-series with Louis Jourdan; Dracula (1979) with Frank Langella; Francis Ford Coppola’s visually ravishing Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) featuring Gary Oldman; Guy Maddin’s silent ballet adaptation Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002); the Italian tv movie Dracula (2002) with Patrick Bergin that updates the story to the present day; the BBC tv movie Dracula (2006) with Marc Warren; the low-budget modernised Dracula (2009); Dario Argento’s Dracula (2012) with Thomas Kretschmann as Dracula; the low-budget Canadian Terror of Dracula (2012) with director Anthony D.P. Mann as Dracula; the tv series Dracula (2013-4) with Jonathan Rhys Meyers; the BBC mini-series Dracula (2020) starring Claes Bang; Bram Stoker’s Van Helsing (2021), which actually features no Dracula; The Asylum’s Dracula: The Original Living Vampire (2022) with Jake Herbert, which actually features no Dracula; the remake of Nosferatu (2024) with Bill Skarsgård; and Luc Besson’s Dracula: A Love Tale (2025).

Full film available here